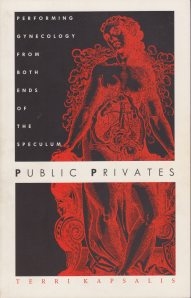

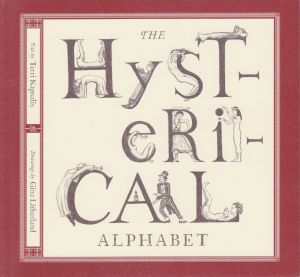

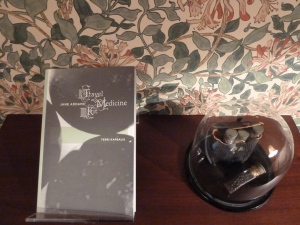

Terri Kapsalis is a writer, performer, and cultural critic whose work appears in such publications as Short Fiction, Denver Quarterly, Parakeet, The Baffler, New Formations and Public. She is the author of Jane Addams’ Travel Medicine Kit (Hull-House Museum), The Hysterical Alphabet (WhiteWalls) and Public Privates: Performing Gynecology from Both Ends of the Speculum (Duke University Press) and the co-editor of two books related to the musician Sun Ra. As an improvising violinist, Kapsalis has a discography that includes work with Tony Conrad, David Grubbs, and Mats Gustafsson, and she is a founding member of Theater Oobleck. She works as a health educator at Chicago Women’s Health Center and teaches at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Kapsalis was interviewed in June of 2012.

Daniel Tucker (DT): Can you speak a little bit to some of the pre-histories of Theater Oobleck, what were some of the experiences that people, yourself included, were bringing to a project like that and what some of the artistic or theater reference points that people were bringing to it? What was the sort of mix of ideas and influences that kind of brought it together?

Terri Kapsalis (TK): So many different things. We were just going through this as a group online, with everybody throwing in a bunch of different things. In Ann Arbor, in 1983, I believe, was the very first Streetlight production. When Streetlight actually moved as a group to Chicago in 1988, there was another group in Chicago already called Streetlight so there had to be a new name for our group and Oobleck is what came out, the green goo that falls down on the king and gucks things up, from Dr. Seuss’s Bartholomew and the Ooblecks. A lot of people involved in Streetlight were committed anarchists. There was a strong interest in Brecht, there was a professor in the Residential College at The University of Michigan that a lot of people had studied with, I believe his name was Martin Walsh, who taught Brecht, and there was a Brecht company there, and so Brecht was definitely an influence. There was a punk rock contingent. A number of people had bands and were playing music a lot. So, it was this interesting mix of theater threads, political threads, and a lot of different aesthetics. There was an interest in conventional theater, but there was a deep questioning of the politics of theater and the way its made. The first groups of short plays that were performed under Streetlight were done with directors, but very quickly, and I believe we figured out that it was with Mickle Maher’s first full length production for Streetlight called King Cow! in 1985 that he wrote this little manifesto about getting rid of the director and passed it out at the performances, and that was the first play that really started pushing the kind of politics of the group to the politics of the making of the work. And eliminating the director.

DT: Just to clarify about that event, of like the passing out of the manifesto, was that actually in response to a play that had a director? Or was it an explanation for why that particular play didn’t have a director? I mean, was it an antagonistic thing internally or?

TK: No, as far as I know it was not. I was not involved in that production but as far as I know it was not internal antagonism, it was more of a stating it to the people. That it’s time to be done with the director, that the director has had his time and his time is over and that’s done. Working without a director has become over the years, the ‘Do Not Pass Go’ of Theater Oobleck. You do not work with a director in Oobleck. And Oobleck has maintained that there are these advantages to doing that, that, for us, outweigh the disadvantages. And critics over the years would complain about the director-less theater and “oh, how Oobleck could use a director!”

DT: [chuckles]

TK: But I think we all would say that we gained a lot from not going that direction.

DT: Yeah. And what about for yourself, You were a student, then, when you got involved in Oobleck. But were some of the reference points or ideas that you were bringing into this? I’m imagining this was a super interesting new world of ensemble theater production that you fell into, or was that something you had worked in before?

TK: No, I mean, I was a freshman in college, so I was coming straight out of high school theater productions, which I did a bunch of with really amazing people. I happened to go to this high school that had great theater. I did all of these plays with people who now have big careers in movies and television and stuff like that, so I had that kind of conventional training –how to create a character, how to listen to a director.

I was living in the Residential College dorm and there was a flyer on the wall saying “come audition for a set of short plays,” and I showed up for the audition and there were two guys sitting there and the room was empty and they said, “oh, well, we already gave all the parts away to our friends. But if you want to be part of it, you can go write your own play.” And I was like, “what!?” So I went and I wrote a play, I wrote this short play, and I think I cast the two guys who were sitting on the table! [laughs] And it was me, Danny Thompson and Chris Faber.. And that was the beginning of my Streetlight career. And pretty quickly, the experience got me thinking critically about the world of theater and performance which was so much about this dependence on the audition and being accepted for roles in order to do the work that you wanted to do. And, why not just go write your own thing? That was an important realization for me.

DT: And what were some of the early Oobleck/Streetlight projects that you were involved in? I mean, you don’t have to represent the whole history, but just like some of the stuff you were involved in?

TK: I counted at one point I was in over thirty Oobleck productions, Streetlight/Oobleck productions so yeah, it’s a lot. But those early ones…

DT: The kind of ones that really made an impression on you, do you think?

TK: Yes, the first one we did out of the residential college was a play by Danny Thompson called El Presidente is Not Himself Tomorrow. That was a large ensemble production performed at a place in Ann Arbor called the Performance Network and a lot of people came. It was a large production with a large cast and it had this incredible energy. There was group writing that happened which was interesting, so that left an impression. From the early Chicago days, doing Jeff Dorchen’s Ugly’s First World was an incredible experience. It was a super complicated play that, to this day, I still think I don’t understand even though I performed it many, many times. But, it was this energy. And I think that, for me, that’s what really sticks about the early Streetlight days and the early Oobleck days, and it continues until now.

I just got an email reporting from New York what’s going on with the Hunchback Variations Opera which is at 5959 in New York right now. They’re performing to sold out audiences, people are freaking out, people are crying, just, this tremendous energy. And what’s interesting about that production is that it is comprised of two opera singers and two musicians, none of whom have worked with Oobleck before, so they were suddenly thrown into this director-less process. They took it and ran with it, and are just having the time of their lives, because of the brilliance of Mickle Maher’s words and Mark Messing’s music. They’re blown away. The brilliance of those words and music come very much out of that kind of energy that I’m talking about. So that energy really translates.

I remember always pulling things off by the skin of our chins, you know. A kind of mad rush to get things up and happening, and working, and it being very exciting, and partly because there was nobody you could blame anything on. You wrote the words. You were performing them. You didn’t have a director that you could blame things on. Part of the Oobleck thing was that the playwright was always in the play. So there was no potential for the playwright to have that kind of outside position from which he or she could look down and say “no no no no, that’s not right,” and assume a directorial position.

DT: Right. Yeah, I was always curious about that.

TK: And that’s shifted a little bit now. Sometimes people get to a certain age or a certain point in their career when they want to focus on the writing and they don’t want to focus on the performing. So, in Mickle’s case, for the last number of productions, there have been times when he’s stepped out and hasn’t performed. So that’s a shift that has happened of late.

DT: Because of all of these decisions that were made about how to produce an Oobleck play then did you, did it result in a lot of energy being spent in kind of like group process, actually negotiating the kind of group decision making?

TK: Oh yeah. And some of it was kind of gruesome, as those things can go. I remember the weekend meetings that would go on endlessly with a bunch of smelly friends, not pleasant kinds of situations! A lot of it was about process, and really, agonizingly long rehearsals. You’d run a scene or you’d run the show and then everybody would sit together and everybody would give notes, including the people who came along to be what we called “outside eyes.” They were the people who were invited, that we knew, and potentially they would bring people too, to come along and give notes. And you know, before we got really smart about the rule for performers of “just listen, just take notes,” you know “don’t talk back,” before we got smart about that, those things could go on forever. Certain long-winded friends would come and they would give tremendous amounts of notes. And then there would be arguments, and then there would be discussions. That’s where the rule Actor’s Prerogative came from, which was the idea that, in the end, the person who spoke the line or did the action was the one who had the final decision, so that it wasn’t by group consensus or it wasn’t by some kind of democratic voting process that we decided what I, as a performer, would or wouldn’t do. That I would accept the notes, synthesize, decide what I was interested in taking, what I was interested in leaving behind, and then based on that, I would make a decision about how to proceed.

DT: So just a little bit more about Oobleck, but to kind of get to Chicago…I dunno if everyone was at the same point in their lives or how this worked, but it’s not so common to have a theater company or even a group of friends all just sorta pick up and move somewhere together. Can you talk a little bit about what the thinking behind that was?

TK: Yeah, well, what’s interesting was that I was not involved in that process, because I was already here. I was already in Chicago because I had had an automobile accident and I was in intensive physical therapy and was living in my parents’ house in Evanston. So I happened to be around when everybody in Ann Arbor decided, okay, now it’s time to leave Ann Arbor, and I was like, “cool, ‘cause I’m already there.” So a lot of people had agreed that, after a certain point, Ann Arbor was a place to leave. If you’re doing theater and it’s about developing an audience and about getting more ambitious in terms of what you’re doing. And we had had great success in Ann Arbor, and had huge audiences, and were getting lots of media attention, you know, as much as possible, and I think the decision was “time to move on.” But I was not involved in those conversations. I think they would have been fascinating, and it was just this weird kind of coincidence that I was already here. I was from Chicago. But few people had roots here. They were mostly people from Michigan, deciding to come to a new city.

DT: Did the fact that you sort of had roots here, end up, kind of, when this gang of your friends and stuff shows up, did that kind of inform anything about how you all started to work, that you kind of…

TK: My roots, no, I don’t think so, because while I was still not as active they all found this space that they started working on, working at. It was near Elston and Armitage. It was a place called Café Voltaire and they had a theater space in the back…Cabaret Voltaire. And that’s where some amazing work happened, Mickle Maher’s play Pope is not a Eunuch, Jeff Dorchen’s play The Slow and Painful Death of Sam Shepherd. Really remarkable early Oobleck stuff happened there and the energy started picking up. And I got re-involved toward the end of Cabaret Voltaire once we ended up moving to the little space on Broadway near Irving Park, second floor space, not going to remember the name of it, and then after that we started the space which is now where the Neofuturists are. I think it had been some kind of Swedish meeting hall, or something, and we adopted that space.

DT: And so to wrap up that period…I’m imagining somewhat a sort of like transitional phase for the group of like adapting to a new city and you getting back involved. What were the kind of, the other practitioners that you all were interacting with? What was the other stuff in your orbit? The other activities? I don’t even want to narrow it to theater, because it probably was broader than that? Just kinda what was the community like, I guess?

TK: A lot of it was around theater and performance, I mean, certainly Curious Theatre Branch and Maestro Subgum and the Whole. We were close friends and compatriots. There was back and forth with folks in the Neofuturists. That was a little later. A lot of theater going. It’s interesting because I don’t have a great memory, but also I just think in some ways that what we were doing was so all-consuming that my mind doesn’t really go a lot outside of that work, you know? I mean, it was too, we were putting on a phenomenal amount of work, it was really one show after another after another, because, for instance, we didn’t have nonprofit status, we had no grants, we had no money coming in from donations, individual donors (maybe there were a few individual donors) but we were paying monthly rent on a space and keeping the whole thing going from “pay what you can” at the door.

And then everybody had odd jobs, day jobs in different things that they were doing to kind of keep themselves afloat, and so my mind doesn’t go to “oh there was…” yeah, so I don’t go there.

DT: What about the content, like what kind of conversations were happening around the content? Because as far as I can tell from a distance it’s quite eclectic, I mean, you had all this sort of intentionality around the process, but what other kind of intentionality existed around either the form or the content, you know?

TK: I mean, it’s so hard because we’re talking about literally a twenty-five year span, so I can think about one area and my mind goes one direction and I think about another and my mind goes another direction…

DT: Well, just a few, the odd anecdote or something. It doesn’t have to line up historically, ‘cause I’m going to move on to other stuff.

TK: I mean, the current political situation at the time was completely impacting things. So a lot of the plays, even though they may seem to be in their own little worlds, were definitely in conversation with whatever the political pressures of the time were…and I mean, because it’s a playwright’s theater, each playwright was so idiosyncratic that they brought their idiosyncrasies into their shows. So, David Issacson’s play Somalia, Etc. seemed like this just kind of chaotic circus of these different things happening but it was all very much about North Korean and South Korean politics at the time, what was going on in Somalia, what was going on in these different parts of the world and that was all coming together. But I mean, when I think of the people in Oobleck, avid readers and intellectuals. If anything, maybe people who were coming to lecture at different local universities might have had as much impact on the plays as what was going on in the theater in Chicago.

DT: So people were actively participating in conversations outside of theater?

TK: Yeah, I think that was super important to what was going on. I was always just blown away by how widely read people were. I think one thing that a lot of the plays have in common, if one were to look at the span of them, was the importance of research, and the importance of historical material and biography. You know, real interest in historical figures, obscure historical figures, like Alistair Crowley as a character in Ugly’s First World. There were broad possibilities with regard to what might enter the play. So in that sense Oobleck was different, not the regular “let’s take a particular historical event and create a play around it” it was much more this mash-up of different aesthetic and historical references so it’s hard to keep up with. And then there was Robin Harutunian’s wild play In Cheap Shoes which doesn’t fit that at all. More like Edward Albee meets Raymond Chandler meets Judy Tenuta. I hope that’s a good enough answer! [chuckles]

DT: Oh yeah, totally. I want to transition into other stuff like your decision to study Performance Studies at Northwestern. How much did this like kind of come from questions that were produced for yourself in Oobleck or concerns that were produced in Oobleck?

TK: Not, not that I was aware of. I mean, as much as Streetlight was a huge part of my life in college, and so I had this interest in performance and this interest in theater and an interest in how politics related to those things. As an undergrad I was an anthropology major, and then I learned about this strange discipline called Performance Studies which seemed to have one in anthropology and one leg in performance. I stepped into it backwards. I had no idea what I was getting into and what people do with doctorates. I had no idea how those things worked. What I was really intrigued by with Oobleck, as much as anything, was working methods and power structures, and how those things operated. And that certainly was connected to critical theory and cultural studies and anthropology and things like that. So that’s how I got into Performance Studies, but in a way, those worlds were kept quite separate. So, when I started the Performance Studies degree, I was still doing all these Oobleck performances, but they didn’t really count within academia, within my academic work. I mean, that was kind of interesting to folks, “oh, she does this theater stuff,” but it wasn’t like, necessarily part of my degree.

DT: Yeah, so what kind of conversations took place for you around being a practitioner in these fields that were actually the fields that kind of intersected with your research of theater and health? What kind of conversations took place within the academy around you being an actual theater and health practitioner, which were the subjects of your research?

TK: Yeah, like, well, the health thing came toward the end. I mean, I had been working at Planned Parenthood before I went to graduate school. I never thought that my work in women’s health would have anything to do with Performance Studies, it didn’t even dawn on me until I had this “oh, wow” moment which I talk about in the introduction to what was my dissertation, and is now my book Public Privates. I was supposed to b e at a Performance Studies conference, seeing my professor Dwight Conquergood give a lecture about gangs in Chicago and gang performance, gang symbolism. And I really wanted to be at his lecture at this Performance Studies conference, but I had agreed to teach medical students breast and pelvic exam, which I did to support myself through graduate school, never thinking it had anything to do with performance.

e at a Performance Studies conference, seeing my professor Dwight Conquergood give a lecture about gangs in Chicago and gang performance, gang symbolism. And I really wanted to be at his lecture at this Performance Studies conference, but I had agreed to teach medical students breast and pelvic exam, which I did to support myself through graduate school, never thinking it had anything to do with performance.

And then I’m on the table, teaching these medical students breast and pelvic exam, wanting to be at this Performance Studies conference, and watching these students try to find my cervix and I’m directing things and I’m laughing about this or that, and thinking, “god, this is such a fucking circus!” and then realizing, oh, wait, this is the performance. Like, okay, that’s the Performance Studies conference but this is the performance. And that realization, “so, here is this thing I did for money” right, that I also really believed in and thought was some of the most important political action I’d ever done, which was to teach medical students how to communicate and how to be good providers in terms of an exam that is quite difficult to do and is really all about communication—it’s not mechanically difficult, it’s just about attitudes and all kinds of things. So, it always felt like important political work but I never made the connection between that and performance. Performance Studies was the place for that project, and realizing that I could write about gynecology as performance was where it all came together for me.

And then I started thinking about how work with Oobleck has always been about this issue of power, and this issue of what does it mean to make something without a director, and what does it mean for the actor who is often a person who takes direction and is told what to do, when that person takes more authority and more control and maybe even writes their own material, you know, that was the place where it all came together for me.

But that wasn’t what I entered into graduate school talking about. I entered into graduate school thinking “oh my god I’m completely undereducated and all this critical theory and postmodernism shit that everybody’s talking about, what am I doing?” And so I spent two years going “whaaa?!” and trying to get my bearings, but in my head , I think some of those connections were starting to be made. But Oobleck, if I had been involved with Oobleck for twenty-five years and if it was this kind of entity that it is now, I could have written my dissertation on Oobleck. But at the time, it was like “oh, no, this is just this thing that’s moving and happening and becoming a constellation.”

DT: And so how was that received, that you kind of took these life practices that you had that, like, and then sort of started introducing them more into the research? I mean, was that, was that kind of an acceptable move to make?

TK: It was, because of the ethnographic component of things. So, Dwight Conquergood and Margaret Drewal who were part of that department and were very respectful of firsthand knowledge and the ethnographic turn and the idea that being a participant is a form of research, being a performer is a form of research. In that program I had permission to do things that I can’t imagine really having permission to do in almost any other discipline or department. It really allowed me to put things together, and I’m very grateful for that. I didn’t have to do some of the hoop jumping that I would have had to do if I was in, say, a sociology department. So, it was idiosyncratic, ethnographic research, and there was interest in creative critical writing practices, and other ways of knowing that weren’t your conventional ways of knowing. And people were also open to the fact that, for instance, nobody on my committee had a background in medicine or health, and they were willing to take the things they were familiar with and have them applied to this new area.

DT: A few minutes ago when you were talking about when you made the connection between your sort of health practice and the Oobleck work…I guess I’m wondering at what point free-improvised music came in, because it’s another sort of layer of your practice that deals with similar kind of themes in terms of social dynamics or collaborative kind of relationships.

TK: I want to address first that I started training at Chicago Women’s Health Center in early ’91, and that was in my second year of graduate school. So I actually started training at the clinic just as I was coming into these ideas about gynecology and medicine in relationship to performance.

And then also it was soon after that or right around the same time that I started playing violin again. I had been classically trained as a child, before I did theater, and then because of that car accident I had, which screwed up my left hand, I could never go back to playing violin the same way I had played violin before, so I needed to invent a new relationship to the instrument. And it was a play, I think it was in one of Jeff Dorchen’s plays, Mysticeti and the Mandelbrot Set for which I picked up the violin again for the first time and used the violin while performing in that play. And then getting together with John Corbett, which also happened at that time—those were busy years, ’90, ’91—you know, then also being exposed for the first time to free-improvised music, which I knew nothing about at all before I met John. All those things started making sense in a different way too.

And yeah, there’s no question that that issue of, how do groups of people make things together in a way that is undetermined and in a way that is about power sharing or about—power sharing isn’t quite right—is about shifts of power between people, that isn’t as prescribed as we might normally think of power as working.

In the days that I was writing that project, Public Privates, the gynecology project, I wasn’t as involved yet in free-improvised music as I would be later. So it was more that I was thinking about Oobleck, I was thinking about Chicago Women’s Health Center, and I was thinking about how medical students have been trained in pelvic and breast exams. And it was Dave Buchen, a member of Oobleck, who introduced me to James Marion Sims, who is considered the father of modern gynecology, who was a slave owner who kept slaves in his backyard hospital and practiced un-anesthetized vaginal surgery on them. So, as I was working on this, these things started opening up, these issues of power and history and gender and race and how all of these things played out..

DT: Which kind of suggests also that you were talking, that you were talking to your sort of theater people about your research and your health stuff and maybe were you also sort of talking to these health people about the kind of fact that you also did these other things, I mean, did you keep these worlds separate? Or did you acknowledge that you had this kind of set of concerns that were kind of interrelated but were also totally separate spheres in a lot of ways.

TK: I probably kept them more separate than I should have or than I needed to, partly because when you’re trying to figure something out, there can almost be a superstition about talking about your ideas too much. Or at least, maybe that’s how it works for me. Sometimes, until I’ve got a grasp of something, I don’t necessarily want to talk about it all over the place because I’m trying to figure it out. But obviously, yeah, I must have talked about it to some extent. People would ask, “What are you doing over there? What are you doing over there?” But to this day, I still don’t talk a lot about one sphere while in the other. I don’t necessarily talk a whole lot at the clinic about what I’m doing performance-wise. And I don’t necessarily talk to Oobleck folks so much about what I might be working on outside of performance. So I guess my head has been the locus for making those connections. But then of course there are these amazing things, like Dave Buchen who obviously I must have been talking to about my dissertation who said, “well do you know about this guy James Marion Sims? Check this out!” And responding, “Whoa!”

DT: Well, this is a fast-forward, but it seems like at some point there started to be, and I don’t actually, I haven’t seen any of this work, but I’ve been kind of going through the Oobleck chronology of plays, it seemed that there were a few that you were involved with that might have been a reference to like women’s bodies in some kind of sense? Then more specifically, like your Hysterical Alphabet project…I know that it’s different than what your dissertation was, but was that sort of in any way a kind of performative extension of that research?

TK: Yeah. Totally. And now that you’re saying that, because I have such a bad memory!—but I’m remembering Wylie Goodman and I did a piece called Girls Who Didn’t Like Horses, and it was a group of short pieces that we did, that was very much a response to reading Freud [laughs]. Wylie was also in graduate school at the time getting her doctorate in counseling psychology. And of course as a good cultural studies/Performance Studies person I was reading Freud and Lacan and people like that, so we created this piece Girls Who Didn’t Like Horses which was a response to what we were reading. Which was incredibly fun. I think we performed that at an academic conference, but then also in a Theater Oobleck context. And then a piece called, I think another piece we did together, or maybe it was just me solo, I can’t remember, but called The Birds and the Bees, Without the Bees, which was also dealing with some of the same that I would deal with later. And then a play with Jane Richlovsky called A Body Can Be a Worry to Anyone, or A Box to Contain our Solutions, which was also a collaborative piece. So, I was doing work that was playing with some of these different ideas that I was thinking about in school, so they weren’t completely separate, absolutely. And then the Hysterical Alphabet came out of…

Letter “H” from The Hysterical Alphabet, drawings by Gina Litherland, text by Terri Kapsalis, WhiteWalls, 2008

DT: Would you explain what that was?

TK: Oh, sure. The Hysterical Alphabet began as a collaborative book project with a visual artist named Gina Litherland. She, like me, was very interested in the history of hysteria, which I had come to and started writing a little bit about in my first book Public Privates. In that book, I thinking about the history of hysteria and how it related to the diagnosis of acting out and improper female performance, and how this 19th century diagnosis—that’s what I was looking at, the 19th century history of the diagnosis—was related to some of the ideas of improper female performance within the gynecological scenario. And there were some interesting connections. So that’s where I first became aware of hysteria as an actual diagnosis. And the more I read about it, the more I realized it had this much larger history that went back to Ancient Egypt, and that went all the way up to the 1950s and, one could argue, up until today, and my friend Gina thought about and read a lot about hysteria from the perspective of the surrealist interest in hysteria, but she was also interested in the history of witch trials and fairy tales and where that all comes together. So, we started having this series of conversations, and the first project that came out of these conversations was the Hysterical Alphabet book, which is an alphabet book, like a Victorian children’s alphabet book, but one based on primary medical writings from Ancient Egypt to the present. The alphabet serves as a chronology of fictional case studies that takes us from A in Ancient Egypt to Z, now. Gina did these amazing drawings of the letters of the alphabet and different elements that we used in the book, and I wrote the text.

I think Mickle Maher was curating an evening of Oobleck-related stuff and asked me if I wanted to do something, and I thought, it would be interesting to do a reading of what I’d written so far, which was, at that point A through L, the first half of the alphabet. Since I had a history of structuring improvised sound with text, I asked John Corbett if he’d be interested in collaborating with me. I structured the first half of the alphabet, he would use his turntable and other sound-making devices. So we did that at Links Hall, A through L, and got great response, Then, I think David Issacson was curating another thing for Oobleck, and said, “you wanna do something? Why don’t you do that again?” and I was thought, “well, we just did that.” So, I took the recording that we had of that first night of A through L and I sent it to Danny Thompson, who at that time was starting to make these video collages. Danny was the very first person I had ever worked with in Oobleck, so I had been working with him since I was 18. I sent that first half to Danny, and he made these amazing short video collages, and so we performed A through L with those. We all agreed that it was a very fun project. So as I kept writing and working through the book project with Gina, I would send things to Danny and he would make more video collages, and then that ended up being a performance, which was a very different project than the book project—Danny never looked at Gina’s drawings before he finished the video, Gina never looked at Danny’s video until everything was done with the book, so it had this double life. And I think that Hysterical Alphabet is a project that bridges all those different worlds, actually, finally. Right?

DT: Yeah!

TK: It has the Oobleck connection, it has an academic connection. I mean, there’s a huge academic—huge, I don’t know—there’s a large group of people interested in hysteria, within academia, dubbed, I forget by whom, maybe Elaine Showalter “The New Hysterians.” People that find hysteria to be a very productive topic for thinking about all different kinds of things, historically and with regard to contemporary culture. So that project does blend academic, the sound work that I’ve done, the performance work that I’ve done, the work with Oobleck, and it relates to the medical in a more theoretical way as well.

TK: It has the Oobleck connection, it has an academic connection. I mean, there’s a huge academic—huge, I don’t know—there’s a large group of people interested in hysteria, within academia, dubbed, I forget by whom, maybe Elaine Showalter “The New Hysterians.” People that find hysteria to be a very productive topic for thinking about all different kinds of things, historically and with regard to contemporary culture. So that project does blend academic, the sound work that I’ve done, the performance work that I’ve done, the work with Oobleck, and it relates to the medical in a more theoretical way as well.

DT: And would you, with a project like that, that is also more recent, would you attempt to kind of engage people from some of these different worlds, to come out and see it and then kind of know a little bit about what you’re doing…what were some of those responses like?

TK: Yeah, that has been really interesting, to perform to an audience that has people that I work with at the Health Center, combined with people from the Chicago theater world and Oobleck, people that I teach with at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and people that I’ve done improvised music with. And to have all those different constituencies represented. And it’s been encouraging, because people have engaged with it in different ways, which has been very exciting. Some people get really into and excited by the ideas. I’ve had art students come up to me, a couple of different MFA students at other institutions come up to me and say that it really inspired them and they wanted to get into the studio, and I thought, great. So, that makes me excited. And then we were brought out to Emory [in Atlanta], to perform the piece as an example of hybrid scholarship, and new scholarship and alternative ways of presenting research. Great, cool, okay. It’s been written about by academics and by theater critics and by book critics. You know, so in these different venues, so that’s when it starts getting really exciting. And it’s hard, it’s hard on the head because if I start wearing those different hats and look at the piece, I might want to push it in one direction or another. How to let it be its weird hybrid self and not do that. Not push it towards the academic side or push it towards the theatrical in the sense of more acceptable theater practice, you know?

DT: Right. I have some questions kind of about audience with that, ‘cause it does seem like you kind of get a lot out of the multiple audience thing, but is that, is that something that’s become necessary for you in your kind of cultural production? Sort of, in your knowledge work also, to actually kind of consider how it could exist for multiple audiences or are you sort of fine with doing stuff that’s kind of more, I mean, I’m not saying this negatively, but a more narrowly distributed focus?

Still from Noon Moons (18 min.), animation by Rob Shaw, soundtrack by Terri Kapsalis and The Eternals, 2012. Commissioned by Experimental Sound Studio/Sun Ra/El Saturn archives. View at noonmoons.com

TK: Oh yeah, I’m totally fine with that. I’m thinking about the New Moons piece that I just did with Damon Locks and Wayne Montana from the Eternals—of the Eternals, they are the Eternals—and animator Rob Shaw, which is going to have a totally different interest and audience, and in some ways it might be a broader audience, in some ways it might be a narrower audience, and that’s totally fine with me. I mean, in some ways I want to make work, I’ve always wanted to make work that could reach people that I didn’t necessarily set out to reach. That would have that potential of interesting people, that I might not anticipate would be interested in the work. That’s exciting to me. But it doesn’t have to be broadly accessible or of interest to everybody. I know a lot of my work is idiosyncratic and might completely turn off certain people, and that’s fine. There is a wonderful improviser, Ladonna Smith, who used to say, “if you don’t piss somebody off, you’re not doing your job,” and I guess I ascribe to that in some way, it’s fine to do work that pisses somebody off.

DT: And I can imagine that that’s kind of something that gets talked about a fair amount with free-improvised music where oftentimes the audience is sort of made up entirely of musicians, in a way that is not necessarily the case with theater production. You know, would you find that to be true?

TK: Well, not necessarily entirely musicians, but entirely hardcore fans. You know, people who know what they’re getting into, know why it interests them. So, when you take those practices out of that context, it can be really unnerving. If you know you’re playing in front of people that are not used to freely improvised music, it’s, yeah, it’s jumping without a net, it’s really like “whoa, what’s going on here!” and I don’t know if I have the guts for that level of, I mean, that’s scary. I mean, I’ve done it, and it’s wild. It’s like you’re speaking a language and you’re speaking a language that people in the audience may not have access to at all. But then there may be people in the audience that get really excited and really turned on who have never been exposed to it before. So that can be really exciting. And there are even parts of the sound work in Hysterical Alphabet that may be off-putting to people in the way that certain freely improvised music concerts are off-putting to people. And that to me can be really exciting, too.

DT: To continue with the music, is, I mean, you never, we didn’t quite get into the story of you embarking into that world, which is this whole other world and it’s not necessarily connected to the things you were doing before, even though it could conceptually have some overlap, I mean, what was that like, like you’re kind of entering this world which is quite healthy and robust here in Chicago, what were some of your early experiences with like participating in that world? Did you enter it initially as a participant, or did you enter it kind of as an observer and then start participating?

TK: Yeah definitely, started as a listener, and was really curious, and trying to figure it out, and immediately realized that I was not so interested in listening to recordings of improvised music, that for me it was very much of a live act, and that I was intrigued and interested in being an audience member and not so much in being a listener of a recorded music object. And early on John asked me if I wanted to start playing, and he and I played some together, and then we had a trio with Hal Rammel. I wrote some texts for that trio that we would perform. That was exciting to me. I was familiar with the spoken word, I was familiar with playing violin, and then I was really intrigued by this mix of things. At the time that I was playing, it was such an exciting time in Chicago for new music, so I had some really incredible experiences, now looking back, dynamic experiences with incredible musicians.

DT: What were some of those settings or places? Just to sort of give some reference points…

TK: Tony Conrad, filmmaker, musician, came to town to do a project, and he’s very interested in ways of tuning string instruments so that one is able to play very close frequencies and that creates a “beating” that comes each time the two frequencies coincide. Tony thinks of this “beating” as a metaphor for individuals and our relationships to one another. There’s a way we fit together that’s close, but not alike. Tony likes really cheap violins, very cheap, bad sounding instruments. Which was completely fascinating to me. So I have this memory of recording an album with him which became his record Slapping Pythagoras, I think it was in the basement of Steve Albini’s old studio, I’m not necessarily remembering exactly. And it was a whole bunch of guitarists and then me and Tony playing all these weird violins and Jim O’Rourke produced it, and thinking “okay, what is this going to sound like?” you know, because just being in the space hearing this stuff, thinking “Wow” and then Jim mixed it in this beautiful way and it ended up being this fascinating CD. So I had the opportunity to step into these very interesting projects. But then, there was a point where I wasn’t practicing enough and something had to go, and just realizing that if I was going to do right by the music, it requires a lot of work, and a lot of practicing. I was feeling a bit like a dilettante and that I was just not doing enough to further the music.

DT: So that’s something you stopped?

TK: Yeah.

DT: Okay. And you mean, like, officially?

TK: Yeah, I stopped it, I don’t know, seven years ago, six, seven years ago, maybe more. But I also hear Michiko Ititani’s voice in my head, she’s this wonderful painter and person, who when I said to her “yeah, you know, I stopped the violin” she said “oh, no no, Terri, never say you stop anything completely, because you never know when you might need it for something.” So you know I’m hesitant to say, “yeah, it’s over. Being a violinist? Over.” Because I could imagine some day, needing it for something, and recognizing that it’s another tool and it’s another way of working. But for now it is on pause, yup.

DT: Yeah. Well, I have just a few more questions, but one is about gender. So, Theater Oobleck and sort of free-improvised music are like basically kind of men’s, boy’s clubs, even though there are wonderful exceptions to those, to that generalization, but and then you’ve got this other world that you’re a part of, the Chicago Women’s Health Center, you’ve got sort of your academic world, which I would imagine sort of like, I don’t know, is a little more gender-balanced? I don’t know. And I guess I’m just sort of wondering, as you bounce between, what, do you think that it like, I know that these are all things you’re interested in, and care about, but do you think on a social level, has it been also important to you to have these different worlds in order to kind of maintain some kind of symmetry, social symmetry or something?

TK: [chuckles] Yeah! No, I think that’s really interesting. I always think about those questions of balance, and whether balance is something we achieve in short order or long order. Does every day have to be perfectly balanced? Or is a year the unit of time in which we measure balance? So if we have enough rest and relaxation and restorative stuff within a year, then it’s okay if there are periods where we go crazy, as long as, the balance is right? So…

DT: Do you have an answer to that?

TK: No, I don’t! I don’t! I think everybody has a different answer and maybe it shifts over time, like that unit of time is different. Sometimes it’s at the level of the day and other times it’s at the week and other times it’s at the month. But that balance, I think there is in my mind, and this could be very inspired by Sun Ra, and reading a lot of Sun Ra materials, but that there is that need for cosmic balance or cosmic order. So yes, you may have just put your finger on one of those for me, which I think I realized at some point. It was most clear to me when I was doing a lot of improvised music, and spending a lot of time in clubs with men, oftentimes being one of maybe two or three women in the audience. Or, oftentimes, the only woman on the stage.

TK: No, I don’t! I don’t! I think everybody has a different answer and maybe it shifts over time, like that unit of time is different. Sometimes it’s at the level of the day and other times it’s at the week and other times it’s at the month. But that balance, I think there is in my mind, and this could be very inspired by Sun Ra, and reading a lot of Sun Ra materials, but that there is that need for cosmic balance or cosmic order. So yes, you may have just put your finger on one of those for me, which I think I realized at some point. It was most clear to me when I was doing a lot of improvised music, and spending a lot of time in clubs with men, oftentimes being one of maybe two or three women in the audience. Or, oftentimes, the only woman on the stage.

And then going to the Health Center, which had not, you know, not a man amongst us. And laughing, and just thinking “oh my god, my life is so weird, that I go from these extremes.” From extreme to extreme. Yeah, so maybe that is for me, that’s been some kind of unintentional cosmic order.

And now Oobleck feels much more gender-balanced I think, than it ever has. There are some really strong women in Oobleck, that have strong voices, and I love it. And the clinic is becoming much more a place about gender equity, also, just as we culturally shift our ideas about gender and now we’ve had volunteers and board members who are men. A lot is happening around thinking about gender oppression in different ways than we used to think about gender oppression, right? It used to be this kind of simple—there are men and women, and men oppress women and women are oppressed by men, very simple. And I think I’d like to think we’re headed in a much more nuanced direction. If we’re talking about power and performance, those things have to be much more complicated and much more nuanced and not so simplistic. And so I’d like to think that thinking is becoming more nuanced in every realm that we’re talking about, that it’s just not so simple.

DT: I would imagine that there’s a lot of discussion that has to happen in order to collectively develop these new ways of seeing?

TK: For sure.

DT: And does that process and does the sort of Chicago Women’s Health Center process resemble in any way the process of, like, Oobleck?

TK: No.

[both laugh]

Terri Kapsalis, after receiving the 2012 Golden Speculum Award at the Chicago Women’s Health Center Gala, with CWHC director, Jess Kane, to her right.

TK: No, I mean, I think partly because of what the clinic does, and that it’s a service organization and that it’s partly about the relationship between health and gender, right? I mean, that’s a additional two-hour interview about the women’s health movement and the Health Center coming out of the women’s health movement and gender inequities within health and medicine that the women’s health movement was birthed out of. And then, also, at that time the really serious inequities around healthcare for lesbian, bi, queer people. And that the Health Center was really early on addressing a lot of those inequities, and the Health Center has chosen to, and has out of necessity needed to, address a wider net of healthcare inequities as they relate to gender. And personally, and I don’t speak for the Health Center here, I would love to see the Health Center go to a place where it serves everybody, and that we no longer necessarily need that gender lens to define us. Certainly, the lens of gender is always important, everybody needs the kind of healthcare that keeps that lens of gender in mind. But those conversations that happen at the Health Center are fascinating and very intentional.

It has been a very long time that Oobleck has had a meeting where gender has come up at all. And I think it’s played out just much more in terms of how it’s always functioned in Oobleck. Who’s involved, and who’s at the table and how do they use power? And so, I look at what’s going on with Oobleck and gender very much in terms of who’s at the table and what kinds of conversations are happening.

DT: Well, I wasn’t necessarily just suggesting about, does the conversations around gender at the health clinic sort of resemble conversations around gender in Oobleck, I was sort of more speaking generally about the group process versus the

TK: Oh, I see, I see. We make jokes about ourselves at the Health Center, about where we see the vestiges of the kind of “process everything and discuss everything very carefully,” and, you know, the kind of stuff they’d make fun of on Portlandia, right, that kind of very meticulous kind of over-processing potluck-giving kind of thing. It’s so much about individuals, though, and the play of individuals, because having been involved in the Health Center now for twenty-plus years, the kinds of conversations and the way that power functions has shifted so much depending on the individuals involved. And the same with Oobleck. We can have meetings with one group of members and it might have a very different feeling than if it’s a slightly different group of members. But I’d say as people have aged at Oobleck…Here’s a notable difference: the Health Center keeps having younger and younger folks, right, there’s turnover, in a way that now I’m one of the oldest, whereas when I came in I was the youngest. And at Oobleck, I’m still kind of one of the youngest. Even though, you know I’m not that young, well, maybe I’m in the middle now. So it’s not the same level of turnover as the Health Center. And I’ll say that as people have aged in Oobleck and have more life experience and have partners and kids, there’s a different tenor than there was than if one had sat in on a meeting in the 80’s. There was a lot more spit and fire. There’s more humor now. It’s interesting.

DT: I feel like I could keep asking questions about that…

TK: It’s fascinating stuff! It’s totally fascinating.

DT: I do have one

TK: And I don’t mean to evade it.

DT: No, no, I don’t think you are.

TK: Okay.

DT: Something I’ve thought about with your work is that Chicago is the place where it primarily happens. And while it’s not, as far as I can tell, it isn’t ever the subject matter, it seems like you have undoubtedly engaged with the sort of cultural resources that the city offers, like in a kind of quite widespread kind of way.

And that you’ve sort of engaged with a lot of different kinds of institutions and communities ranging from, Links Hall to Whitewalls to the Hyde Park Art Center to, probably dozens of other kind of venues and organizations. And so I guess I just sort of would like to hear you reflect a little bit on kind of the way that the city itself has kind of shaped or informed your practice or the kind of decisions that you make, but also the priorities that are involved in those decisions.

TK: That’s so interesting, because I don’t know how much I’ve actually thought about that. Where I am is super important to the work. And so, because I’m committed to being in Chicago for any number of reasons, I mean, I can’t really ever imagine leaving Chicago because of the the specificities of the institutions like Oobleck and the Health Center are unlike…I mean, it’s not a replicable experience. A place like the Chicago Women’s Health Center doesn’t exist anywhere else in the country as far as we know. And Oobleck because of its unique history and my roots with that history, with both places, I just can’t imagine leaving. As a young person, I would never have known that Chicago would have been so important to me. I don’t think I even thought about being in Chicago or not being in Chicago. But as it’s turned out, just being here and being so firmly rooted in the place, and the people, and the institutions that I’m involved in, I can’t imagine not doing that.

It’s such an interesting city, it’s such a great city and it has such an interesting history and such a variety of resources. It has unlimited material. Just the experience of being invited to do that alternative label for the Hull-House Museum. I could spend the rest of my life researching just the Hull-House. It’s endless, endless material. And then to be able to use the resources of UIC, to be able to then tap into the school of pharmacology and toxicology, which seems to be quite an amazing school that I didn’t even know was here, is just wonderful. So, yeah, I’ve never thought of Chicago as central to my work, but I can’t imagine doing what I’m doing anywhere else but here.

Jane Addams’ Travel Medicine Kit, Terri Kapsalis, Alternative Label in Jane Addams’ bedroom at the Hull-House Museum, 2011. Photo: Rachel Glass (Hull-House Museum http://www.uic.edu/jaddams/hull/)

DT: Yeah.

TK: Right? And all the conversation about the local and site-specificity, and I’ve never really. . . I’ve always thought “yeah, that’s cool” but clearly, that is super important to me too. Because it’s about people in spaces, paying attention to where they are.

DT: Well, just one other thing kind of related to that is that I think that it is actually pretty unique to kind of have two long running affiliations, right? And certainly that comes, I mean, there is something practical about being rooted in a place and that makes it easier to sort of stay involved in something, you know, but I guess I just sort of, maybe this is more of an open-ended thing that you don’t have to engage with necessarily, but I feel like, that it is so unique to just sort of have those—I mean, even to have just one long-running affiliation,

TK: It’s true.

DT: So then rather to have two, and I just kind of wonder for you, what, a lot of the time people look for sort of transformations in their practice via changing settings or changing organizations, maybe not necessarily even a different city, but just changing, they evolve and evolving means doing something dramatically different. Or where they do a project and it leads them to this other place—and I feel like you’ve referenced all sorts of kind of like transformative events, but that they’re sort of like contained within an ongoing participation, even though you’ve done a bunch of other things that happened. I was just wondering if you had anything to say about that?

TK: Well, I think that points to…

DT: Like, how do transformative events happen in a particular way when you’re sort of actually, or maybe in a distinct kind of way, when you’re actually maintaining something rather than like leaving or…

TK: Right. I think it speaks to the specialness of those two institutions. I mean, the fact that they are not static, right? I think sometimes people leave institutions because they grow out of them and the institution—calling Oobleck and the Health Center institutions, I don’t like calling them institutions. You know, groups, or organizations, people leave them because they grow out of them, or the organization becomes static or their interests completely shift. What’s really interesting about Oobleck and the Health Center, both, is that they have evolved and changed over the years and so for me they are still endlessly interesting, because they’re living organisms, they’re not set, they’re adapting to how things around them are shifting, the people are adapting or the people are changing—in the Health Center, the constituencies shift or change, not as much as in many non-profit organizations, but still, there are shifts and changes as younger people continue to come in. I think that’s endlessly fascinating, and to see how there are generational shifts in interests and thinking and ways of working. And with Oobleck, just watching people get older and watching their interests shift. They’re still makers, they’re vibrant, and their work continues to grow. And it’s such an honor to be able to witness, to be really intimate with somebody’s output for decades. To be able to witness how their work shifts and how their writing shifts and how their performing shifts and their interests. So I think it really is a tribute to these two vibrant organizations that are—talk about rare! I mean, you know, there aren’t so many organizations around that started with the women’s health movement that still exist, especially in that vibrant way. And there aren’t so many theater collectives that have existed for so long. I mean you can point to Steppenwolf, but that’s become. . . it started in one place and it’s become this corporation, right? It’s become a whole other kind of thing. It barely resembles what it started as, for better or worse.

So, you know, I feel in a way that I just happened to get hooked up very early with these two interesting entities that I’ve also contributed to, for sure. In some ways, I think I’ve contributed to the Health Center in a more central way, than Oobleck. I think it hit me when I read yourpiece in the Belgian magazine H-Art where you talked about Oobleck and Chicago Women’s Health Center, maybe even in the same article, right, as collectives, and I thought to myself, there isn’t one other person in this city that has been involved in two of these groups from the beginning or from nearly the beginning. That’s when it hit me, “oh isn’t that interesting!” I’ve been involved in both of these groups for over twenty years. I love being able to witness people’s ideas shift and change and I love collaborating. And you don’t necessarily get to collaborate a lot. There’s a fair amount of work that I do in which collaboration is not a possibility.

DT: Like?

TK: Writing. [laughs] Haven’t yet figured out how that can really be wonderfully collaborative, I mean, there are ways but it’s not necessarily ways I’m interested in, so.

DT: Right, right. Well, I think that’s kind of a good note to end on. Otherwise, I had a formal question about your work. I was wondering what you thought of monologues? If you at all sort of identify as a monologist, or, what is that called, is it a monologist? Or is that…where somebody delivers monologues…I guess I just thought that because it seems so many things have incorporated you reading…

TK: Right.

DT: Kind of in this way where it’s not something I’m super familiar with, so my only other reference point for something like that is, like, Spalding Grey?

TK: Yeah.

DT: [chuckles] And it’s not, it’s not, it just, formally? In terms of that being

TK: Right. I’m trying to think of how much of that I’ve actually done. Hysterical Alphabet could be considered that? Oftentimes when I hear “monologist” I think first-person.

DT: yeah, maybe I’m just sort of more talking about

TK: Like, solo?

DT: Reading. Public reading that is distinct from like the way that it is done in literary worlds, where you do a reading?

TK: Right.

DT: Of your writing…or maybe it’s not quite spoken word in the poetry reference, it sort of is reading as your performance.

TK: At some point, I stopped performing in Oobleck plays. I became disinterested in being a body onstage. And so part of what I became interested in was becoming soundtrack. And so I had this vision of doing live soundtrack for video. The Hysterical Alphabet is the first manifestation of that desire, to perform live, but to not be a body on stage. I was definitely doing some spoken word stuff like that with sound improvisation. There’s some of that in Noon Moons, the animation piece. I’m a writer who hears work read aloud when I write it. I also enjoy reading my work in a literary “doing a reading” kind of way. So the spoken word is important to me. But I don’t know if I identify with a particular genre, per se.

DT: Yeah, it’s not important that you do, either. It was more, that was why it was more of a tangent of a question. I don’t feel that it’s important to get you to

TK: Yeah, and that’s of late. That’s just because also in the last year I’ve done a little bit more of that.

DT: I guess I also thought about it ‘cause while I was preparing for the interview I watched this

performance you did at the Renaissance Society that’s online.

TK: Oh, yeah!

DT: The John Cage thing. And I was like, well, okay this is different than my understanding of the Hysterical Alphabet, but it is, it’s like something that formally there’s maybe some similarities.

TK: Sure. Yeah.

DT: And so I guess I don’t think about it a lot as a form, reading aloud as a form.

TK: The other part of my life where that’s come in is through academic lectures, right? Which can be read papers, and, so, I’m thinking about one instance which was super fun. There was a Performance Studies conference, one of the early ones, maybe the first one in Chicago, and John Corbett and I had a group with Ken Vandermark called Wounded Jukebox, which was, we’d say, John on records, Ken Vandermark on reeds, and me on reads. I’d start with just a stack of books and Ken would have his clarinets and saxophones and John would have a turntable and tons of records. We performed at this academic conference, where, we were all set up and I started by reading the beginning of an academic lecture, just reading this paper.

DT: But not yours? Or yours?

TK: Mine. My academic paper, and then it just started devolving. Ken started playing and John started spinning and I started grabbing random books and reading, and you know, people were just like, “what?!” And so this play on the academic lecture, too, it was super fun to twist that and work with that. Because, you know when I was doing Performance Studies there was all this talk about the performative lecture and the performative lecture sometimes went as far as wearing a hat while reading your academic paper, you know.

DT: Did that go away? Did the performative lecture go away?

TK: Ah, no, I think there’s some renewed interest.

DT: ‘Cause I’ve seen some, but not for a few years.

TK: Yeah, I think there’s renewed interest, and I’ve worked with students very recently who were getting their MFAs at the Art Institute who are totally committed to the idea of the performative lecture, like Rebecca Gordon. And I think there are so many great things that can be done. I am interested in the possibilities of the lecture. What does it mean to skew what appears to be a straightforward lecture? And the Hysterical Alphabet performance comes out of that too. Of playing with dominant historical narratives, and authoritative voices, and things like that. So that’s another thread that has nothing to do with [Spalding Grey], but…[laughs]

DT: I know, I know. I actually have so few reference points…

TK: No, but you’ve got Laurie Anderson. A lot of people would say to me, “oh, you play violin and you do spoken word? Laurie Anderson!” and I’m like, “it has little to do with Laurie Anderson. But that’s okay!” [laughs]

DT: Yeah, yeah. No, it’s always kind of difficult like that where you have formal similarities but there’s nothing else in common.

TK: I love reading stuff aloud. Just love reading stuff aloud. I love reading other people’s stuff—don’t have a lot of opportunities to do it, but I love doing it.

3 thoughts on “Terri Kapsalis”