Ann Zelle, a photographer, sculptor, and arts administrator originally from Springfield, IL, began working at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art in 1968, soon after its founding, after studying art in Italy and interning at the Newark Museum. Her main task for the museum was to help set up the North Lawndale art center known as Art & Soul, a collaboration between the MCA and the Conservative Vice Lords. After leaving Chicago she worked at ICOM, the International Council of Museums, and was head of the Photography Program in American University’s School of Communication for many years. Selections from among her photographs are reproduced here by permission.

Rebecca Zorach (RZ): Could you just start by talking a little bit about how you came to find yourself in Chicago in the summer of 1968?

Ann Zelle: I had just spent a year at the Newark Museum in their graduate program in museum studies. That was a great year. I had arrived in Newark less than a month after the Newark riots. This old city museum, the Newark Museum, had always been very connected to outreach and to the city. They were concerned and wanting to continue the philosophy that started with their founder, John Cotton Dana, of serving the city and not being an ivory tower. They were really ahead of their time, because that’s where museums went, later in the 60s, when they got really scared by the riots and, you know, things changing. So, that kind of radicalized me. At the end of this program, we three graduate apprentices took a wonderful trip in a Volkswagen camper down through the South visiting museums, and we went to the American Association of Museums’ annual conference in New Orleans. One of the panels there had John Kinard from the newly-founded Anacostia Museum. I’m not sure who else was on the panel, but it was discussing what to do about the “Black problem,” how to democratize museums, whatever. And it seemed to me what they were saying—not John, but in general—the comments were kind of “Oh, what will we do about this problem?” And so I kind of shot up and shot off my mouth and said that they should just stop thinking that way and think about sharing their resources and making things available to the community rather than thinking they were going to do something to or for the community. Anyway afterwards I had Tom Hoving from the Metropolitan come up and he handed me his card, and several other people, because they didn’t know what to do. So anybody who sounded like they had any idea at all, they were just desperate for. And I met Jan van der Marck, who had just become director of this new museum that I knew about, in Chicago, the Museum of Contemporary Art.

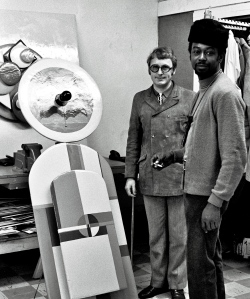

MCA director Jan van der Marck and Art & Soul director Jackie Hetherington with prize winning kinetic sculpture, “Black Madonna and Child” by Reggie Madison. Photo © Ann Zelle

I liked it because the theory was that they would just do happenings, and they’d do exhibits, and they’d be open, and they wouldn’t get tied down to a collection, the way MoMA had sort of gotten frozen around a collection. And I liked Chicago. I had come from Illinois and my family was living in Chicago. So, I talked to Jan and he had already had this idea of trying to work with a group on the West Side to have some kind of art center, a neighborhood museum. He invited me to come back, and I did, after my year was over. I was hired to help organize this neighborhood museum and to work with the group on the West Side, which was a street gang, called the Vice Lords, the Conservative Vice Lords, Incorporated, and help write the proposals and find funding and set up the classes. And teach. So, that’s how I got to Chicago, basically. Until I went to the museums conference, I didn’t really know about this neighborhood museum concept, ’cause it was just starting, but I was definitely interested in museum outreach and in Chicago, so it was a great combination. And Jan was a very visionary person, very happy to go against convention and to do new and different things, and that interested me. So he was a very good mentor for me.

RZ: And when you got to Chicago, was it already clear that the partner for the museum would be the Vice Lords?

AZ: Yes, they were already working with the Vice Lords, and it was a matter of then filling in the community support beyond the Vice Lords. Which makes sense—it wouldn’t make a lot of sense to just go out and work with a teeny group in the middle of the community and not have the community involved. So a lot of what we did was meeting with everybody from the Boys Club to the Catholic Church and up and down the line. And to find funding for this project, but also to find a way to fund it that could protect everybody involved.

RZ: Because it was a risk, for everybody?

AZ: It was a risk—it was kind of an unknown. This was a group of guys who at that point had a little maybe, but not a great track record. They had already gotten some major grants from foundations. They were incorporated [in the state of Illinois] as a nonprofit—it was after that point that a law was passed where to give money to a nonprofit it had to have an IRS certification. You could be incorporated, but [still not have] the nonprofit certification, and the Vice Lords did not have that yet, and as a matter of fact they didn’t get it. Later there was some documentation somewhere, in David Dawley’s book, that the IRS was stonewalling them. It was several years and they still hadn’t gotten it. Which in the end, meant that they weren’t going to be able to get funding from certain places.

RZ: When you first went out to North Lawndale, what did you think, what went through your mind?

AZ: Well, it was just so exciting and so interesting, I don’t think I was, if what you’re wondering is was it sort of scary, no. Was it kind of appalling because it was a really a burnt out, post-riot neighborhood, no. And the side of the Vice Lords that I saw was not threatening in any way, or scary. I didn’t know much about their reputation. I mean to me, it was just a bunch of guys that were doing all these interesting things. When I was there for a while I learned more about their reputation and their history, but at that point they were kind of working against that reputation.

RZ: So it wasn’t like, “oh my god, this is a gigantic task that we’ll never be able to finish?”

AZ: No, not at all! I think part of it, there were such positive people, Jackie Hetherington, that the Vice Lords had found to be the director, and his brother Danny, who was also an artist, to be the assistant director, they were just gung-ho, they were ready to do it.

And Jan was very positive. And the Vice Lords were. They had already had some successful projects. I think Teen Town was in existence by then. I think they had already done some of the neighborhood beautification and things. They knew they could make things work. This was naïve, I’m sure. If I’d known more, thought about it, or just been older, maybe I would have thought it was insurmountable. But no, it was exciting.

RZ: And so what were your workdays like?

AZ: Well, I lived in Old Town, I lived a block from North and Wells, so I would drive my little Volkswagen Bug to the West Side. Sometimes, sometimes. In the beginning I would go to the museum first, because there was nothing on the West Side. I mean, they hadn’t even decided for sure where they were going to have this project, or what building they were going to use. They looked at an old automobile showroom and this and that. So, at the beginning I would go to the museum. Jan spent a lot of time on this project. We would go out to meet with people on the West Side, the various organizations with the Vice Lords, and with funders, and with his own museum trustees. There was putting together a proposal between us and the Vice Lords, so I think it began that way. The first part of it was pretty organizational, pretty much meeting with people. Later then, once it was going, I probably went a little bit after rush hour, probably got there like 9:30 or maybe 10. Things didn’t really happen around there early in the morning. And then stay till 5 or 6, depending if there was something going on in the evening. Mostly it was stuff going on in the daytime, at least in the beginning. There was a huge renovation of this place. These two adjacent storefronts were just in horrible, horrible shape. And we had to break through walls from one to the other and take out all the plumbing and put in new plumbing and put in walls and cement and all that. And the Vice Lords did the work, pretty much.

RZ: How many of them?

AZ: I don’t really know. I can’t answer that because the truth is, mostly while they were doing that, I was out looking for money. You can see I took pictures at the various stages, but I was not really involved in doing the work myself. I kind of wish I had been, cause I would have learned a lot about drywalling and things. But no, at that time I was more on the trying to get the things set up phase. And there were things going on in the museum, shows and stuff, that I was certainly part of. But, later, once it was set up, we were there and ran classes. And just were there to talk to people, and kind of run around the neighborhood, which was fun. And just see all the other organizations, all the things that the Vice Lords were doing. We would visit all the various things. But mostly we were in the shop. There was a small library of African-American history and literature, and people would come in and read. But kids would come in and hang out a lot, because there really wasn’t much in that neighborhood for them at all. There wasn’t anything in that neighborhood for them, except the Vice Lords had set up Teen Town, which was kind of a little pool hall, and they had a little café. One of the things that interested me, and I may have had some stereotypical idea to start with that street guys wouldn’t be interested in art, but they were. They really supported it. There was never, never any suggestion that it was sissy or frivolous or wasn’t important. And that’s interesting. They definitely supported it, they thought it was important. Maybe to some extent also they thought it was a good image for them to put out there. But they liked it, they were very interested in it.

RZ: And what about the other people you talked to, like the potential funders, or the advisory people, do you remember any of those conversations and what they were like?

AZ: Some I remember a little bit from the notes that I took, and I think there was some having to convince people that the Vice Lords were serious and that they were not thugs, that it was a positive thing for the neighborhood. But this was a neighborhood that had been hit bad in the riots, so it wasn’t like there was any competition for an art center or anything else out there. Anything that was there, the Vice Lords put there. So I think at that point they were seen as something positive in the neighborhood, which is not to say that there wasn’t still some gangbanging going on. But I didn’t see much of it. Pretty much they really kept a lid on things. They’d decided they’d all been to jail or been in trouble, and been busted, and kind of saw that that was a dead end. They wanted to do something, set up something better for the next generation. Which was very interesting, you don’t see that happen very much, really, just as a group getting together. People want their own children to rise up and do better, but I think it was a really unusual confluence of ideas and people that was pretty special.

RZ: Can you pinpoint any particular impact that it had?

AZ: Oh yeah. Yeah, definitely, with the kids, particularly the young kids who took the classes and did the art. It seems to me there were more boys, little boys. I say little boys, like, they weren’t teens, they were probably 8-12 years old. Yeah, it meant a lot to them. They didn’t really have very much. It was a very poor neighborhood with limited resources. They may have gotten some things in their schools, but it wasn’t much. And you know, we did more than have art classes. We had poetry readings and plays and, you know, we just made stuff up. So it was fun. It was fun! We had fun and they did too. In terms of long-term impacts, I have no way of knowing, because after I left, I moved away, and then the kind of Vice Lord dream started to fade. I’m not sure what happened to any of the kids. I had no way of keeping track of, or keeping in touch, sad to say, with any of the kids. I hope, I believe, that it showed them some other things, you know, didn’t mean necessarily they’d become artists, didn’t really matter. But I think it added something to their ideas of, and their possibilities of life. And that’s more important than what they’re actually going to be, I think. So yeah, I think that did make a difference.

RZ: You’ve talked about the feeling of optimism in the project. On the one hand there was some urgency from the point of view of White institutions seeing riots and seeing this sort of sense of crisis and wanting to respond to it, but at the same time a sense of possibility, of doing something and making change, and I’m just kind of curious about how you would explain that optimism, maybe even in relation to today, when it seems like maybe there’s not as much optimism.

AZ: Well, it was a very positive thing that was happening, and it was better than anything that had been there before. So, it was an optimistic time, I think. You know, we’ve seen over time that the museums have democratized a little, if you want to use that term. Their staffs are a little more diverse, there are a few more women who are doing something other than teaching in the children’s museum, in the museum field, and there are more minority people coming in.

But, by definition it’s still a pretty rarefied institution that’s based on education and connoisseurship and privileged access to get there. I don’t know how much it changed museums.

RZ: It seems like museums have more of a sense of responsibility to a broader community now than they used to, but sometimes it seems like it’s a matter of just checking off the right boxes.

AZ: Mm-hm.

RZ: And it’s not necessarily the same sense of either urgency or optimism. And maybe it’s good to be modest in one’s ambitions too. But it seems like there’s not the same sense that art can have this kind of public function that could actually help to change conditions in a really devastated neighborhood.

AZ: The other thing that happened with museums is they went into this big numbers game and blockbuster shows and circus stuff. I grew up in museums and I love the old museums, where there’s hardly anybody there, and there’re bones in beautiful old oak cases and it’s quiet and…to me, the classic content, being with the real object, rather than being shoved along with fifty million people and you can’t stop and look at anything. Something is lost in that too, so I don’t know what the answer is.

RZ: Are there things that you remember being challenging or difficult about the project?

AZ: Oh, well, funding was always an issue, always. And that took a lot of time and effort, and it wasn’t what we were in it for, We wanted to be teaching and making art and having fun. As the only girl there, and the only White person except when Jim Houlihan would show up, I have to say as a female I was treated with respect. I can’t remember, I’m sure there might have been occasions when there’d be some jerk who’d say something sexist or whatever. But the Vice Lords, no. They were really on their good behavior. But every once in a while someone would come in. I remember a guy came in with his little boy, little, little guy, like three or four years old or something. And this guy started just haranguing the kid about how he had to practically bow down to me cause I was White, and he had to say “Yes, ma’am,” because I was White. He was a very bitter man, and he was just putting this horrible pressure on this little kid. So every once in a while there’d be something unpleasant like that. But that was very rare, and that was a person with a problem that really wasn’t about me. I mean, it was about racism. You hated to see him doing that to a little child. You can certainly teach children about racism and about all the bad things in society, but to try to just lay bitterness on a little baby kid is not a good idea, I think. It’s not a good way to start off. But that was really unusual.

Was it difficult? That’s funny, I just have pretty much good memories of it, I’m sure there were difficult things, but I’ll have to think about that one.

RZ: And are there particular Vice Lords you remember? So, Jackie and Danny were Vice Lords…

AZ: Mhm. Well, they were of the Vice Lords, they weren’t really…

RZ: They weren’t part of the power structure?

AZ: No, no no no, not at all. Unh-uh. And they hadn’t come up in that neighborhood. They were from Lake Street. They grew up in a little different area, so they weren’t part of the Vice Lord power structure, I don’t know how to say it…

RZ: They were, like, affiliates?

AZ: Yeah. Yeah.

RZ: And were there other gang members who were especially friendly to the art center?

AZ: Yeah, there were. We saw the picture of Fool, standing in front of the Malcolm picture. They came in, Cupid, some of them I would only see down in the office, like Calloway. Everybody came down to the openings. And Al, the big guys didn’t come down that much, they’d come down to just check it out. But Bobby Gore’d come through. I don’t remember any of them who made art there, who came and took any of the classes. But there was a writer’s workshop, and I think some of them were interested in that.

RZ: So there were adult classes? Art classes?

AZ: Mm-hm. Mostly it was for the kids, the art classes were for the kids. But the writers with Kelley, and Peter, were more a group of guys who were interested in writing and reading. Yeah, people would come down if there was a performance or something going on. I say performance, but it would have been something pretty casual. We didn’t have a stage or anything like that.

RZ: But you had a lot of things going on.

AZ: Lot of things going on, yeah. And they would take things out, they took some art, little exhibits out, to some of the schools, local schools. And they’d have school groups in. It wasn’t all that organized—it wasn’t like a museum where you’d have busloads of people coming in, but it was a small place. But definitely, they really made an effort to connect with various groups in the schools and in the neighborhoods.

RZ: And so, were you involved in any of that, did you make any of the contacts with the schools or was that Jackie and Danny?

AZ: I think that was more Jackie and Danny. The people who were on the board, like Better Boys Foundation…I certainly went out to those meetings, but that was, again, more organizational. It really made more sense for Jackie and Danny to do the contacts, in the schools. I couldn’t really represent the Vice Lords as well as they could.

RZ: So, at the time that you were working on Art & Soul, I know that you had heard a little bit about the neighborhood museum movement when you were at the American Association of Museums meeting, but were you aware of other projects? Were you paying attention to other projects and what they were doing, and learning from them?

AZ: Oh yeah. Oh absolutely, absolutely.

RZ: How did you keep up with that?

AZ: Well, through the museums association, anything that was written, and I knew about Anacostia. I mean, just the way you would keep up with something in your field, I knew about all the various museums, and I knew most of the people…

RZ: Before the age of the Internet, I don’t know how exactly people kept up with that kind of thing!

AZ: Oh, that’s interesting.

RZ: I mean, was it newspaper articles, newsletters, talking on the phone…

AZ: Yeah, yeah, and people would say, “Did you know about Ed Spriggs who’s in Harlem?” or “Do you know about this?” and when you’d hear about something you’d write or you’d call. It’s true, we didn’t have the Internet, so it was slower. That’s true. And there was a different sense of camaraderie among the different people who were doing these things, because it was new, and some of these organizations had more and better support than others. And that was really in the end whether they survived or not, just whether they had ongoing support. Cause none of these were money makers, I mean, there was no way that this thing could be self-sustaining. So when in the end things changed for the Vice Lords, things also changed in terms of the [Lyndon B.] Johnson money. The funding was just no longer available for this kind of stuff. Maybe the fear, the threat of the riots and political action faded over time, they didn’t feel as pushed. But they found other ways. I don’t think museums just said “Well, that’s over and we don’t have to worry about it anymore.” But, it’s still—I mean, it’s taken a long time to get women into museums, and into any positions, you know, Chief Curators and things like that, Directors. And it’s the same with minority representation. It’s the same in academia.

RZ: Yeah, yeah. I’m curious about what people are able to learn from experiences in different cities and with different museums too, because it seems like every local situation really was very distinct, but it does seem like these were all springing up at the same time.

AZ: Yeah. I had copies, I don’t know how I got them, but I have copies of the proposals from most of the museums. We traveled some, and there were meetings and seminars, like the one that Allon Schoener spoke at, which was actually just after I left Chicago. So I’m sorry I didn’t get to that one. It sounded like a great group of people. I think there was a real effort to find out. It’s like any research thing. You just spread the word, and anything you hear you follow up on. And you learn from each other. Some of them were more exhibition kind of areas and some of them were more just purely children’s museum kind of places. I’m not even sure, really, what Studio Watts was like—I don’t know that much about what they did. And there were a number of them in different cities, like Cincinnati, Cleveland, that started up and didn’t have an institutional affiliation, or didn’t have the money to continue.

RZ: And so how did you leave Art & Soul?

AZ: How did I leave Art & Soul? My job was over. The museum trustees had committed to fund my position not indefinitely, let’s say, or not permanently. And so that basically ended. And I stayed through that summer, but started applying for jobs and found a job in Washington. As head of the International Council of Museums American branch. I was placed in the American Association of Museums’ offices, so I was right there. I couldn’t have been in a better place to stay in touch with all the things that were going on. And I was very close to the Anacostia Museum and to John Kinard, stayed in touch with him. I always planned to write a book about them, so you can write that book.

RZ: [laughs]

AZ: And Hugues de Varine-Bohan, the director of the International Council of Museums, was fascinated by this stuff, so when he’d come to this country, he’d come to Washington and he and I would go to New York, we’d go to Harlem, we’d go to Bedford-Stuyvesant, to go to the museums. He wanted to see all these places. So I was able to keep in touch with all of them. And later the AAM set up a committee to deal with this. The Museums Association thought that they had to deal with this beyond just having a panel at their annual meeting, so they had a little conference, and I was on that. They planned to do something but they never did it. I guess things fell off, they didn’t feel pressured to do it anymore, but it’s too bad. They came up with a proposal to support these neighborhood museums, but really to support museums in their outreach programs. But trying to help them to find ways to do that, that just went by-the-by.

RZ: Do you think, was Art & Soul unique in being a project of a street gang and a museum?

AZ: Yeah. I think you mean, still, forever. I can’t think of any other, now, and I knew a lot about other projects. Once I was in Washington, some of the Vice Lords came and were part of Youth Organizations United, which was really an euphemism for street gangs, so I knew what a lot of gangs were doing in a lot of cities, and I don’t think any of them had any relationships with museums in the cities they were in. They were doing things, they had programs for kids, like the Panthers, they had breakfasts and all kinds of stuff, but I think the museum connection was rare.

RZ: So, for you, personally, what was the importance of Art & Soul for you—what did you take from it as you moved on?

AZ: What was the importance for me? Well, the whole experience, I have to say, started at the Newark Museum. That was really my experience with another culture and with radical politics and with cultural politics, and all that was carried on through my whole life, I would say. Through Chicago, and into Washington, and the Museums Association and the International thing, and then as a teacher, it was always very important to me and what I tried to impart to my students. It was a rare thing for someone like me to have that kind of access to another world and another culture, and to be in a protected position so that I was safe and I could be doing positive things. It was just a wonderful life-changing experience. So I hope I deserved what I got from it, I hope I’ve been able to use it, and pay it forward, as they say.

RZ: And how about Jackie? Do you want to talk about Jackie?

AZ: Well, Jackie was a wonderful guy. He died quite a while ago, he died too young, He was 52 when he died, and he said he never thought he’d live to 50. He couldn’t believe when he got to his 50th birthday. And if you look at Dave Dawley’s book on the Vice Lords, you will see a list of maybe 30 young men who’re all dead. That wasn’t an exaggeration. I think it’s good that Jackie got out of Chicago. He went back to school every chance he got and he worked, he studied at the Corcoran Museum of Art and he worked in the museum shop. And then went on, and he loved screen-printing. He learned screen-printing there, and went on to work for a number of different screen-printing organizations. He did some of his own artwork as a screen printer, but basically what he really loved were woodcuts. So he became a printmaker, basically, and he just loved doing it. I don’t know what to specifically to say about him. He was always a positive person. He was very cheerful and up and a good person to be around. I don’t know what else to say about him. I miss him. He came from an interesting family, I think. His father was the kind of guy who’d read encyclopedias, you know, he just liked knowledge. And all of his kids were like that. They were all interested in learning, and I think that came from their father. So Jackie and Danny rode their bicycles to the Art Institute when they were little boys and took classes there. It’s kind of nice that in the end then, the Art Institute was one of the sponsors of Art & Soul. They were on the board. I don’t think they gave any money or art supplies or anything, but just that they supported it was really nice, I think.

RZ: I think they offered some African art, at some point.

AZ: That’s right, they did, for the opening.

RZ: I don’t know if it ever actually came.

AZ: I think the masks that I thought were made by the students, I think those were from the Art Institute. When I thought about that again I thought, “boy, those are pretty sophisticated for kids making papier-mâché!” So I think that for the opening that’s probably what they were. And Alan Wardwell was kind of in and out. He wasn’t around a lot, but he was available. I remember we talked to him a number of times.

RZ: And can you say a little bit about Danny?

AZ: The Danski? The Vice Lords loved Danny, and Danny, Danny was one of these artists who would just turn out art, I mean, he was just always drawing and gave everything away. I don’t have anything of his, I’m sorry to say. He was incarcerated several times in his life, and he was one of these artists, that the wardens would all collect his work. He was a very funny guy, and he was a doo-wop singer. I don’t think he was in the Vice Lord group, or maybe he was. They would sing, they’d stand around outside and sing. There was a lot of life on the street, there was a lot of drinking on the street, too. People would get together enough money to buy a bottle of Ripple or Wild Irish Rose, these horrible, horrible wines and share a bottle and they’d just stand around and sing and have a good time. Oh, Jackie was a barber, too, so people would come in to get their hair cut.

RZ: Come into Art & Soul to get a haircut?

AZ: Yeah, yeah, they’d go in the back and get their hair cut. He cut my hair for years, which was great because I didn’t have to go to a barber. But yeah, he was a good barber. Danny, well. Danny was his own person, he just, it’s hard…well, you can look at the pictures, you can see he was a kind of a tall, skinny guy and he had some problems, but he was very generally liked, he was just a likeable guy. I don’t know why the Lords, I think he was kind of a pet to them. They really were fond of him.

RZ: Did he do a lot of portraits? Of them?

AZ: Yes. I wish I had some of his work. He did a lot of work. I wish I’d had a way of hanging onto it.

RZ: So, any final thoughts?

Art & Soul Staff, from L to R: Thurman Kelley (Writer’s Workshop), Daniel Hetherington (Assistant Director), Ann Zelle (Advisor), Jackie Hetherington (Director), James Houlihan (Advisor), Peter Gilbert (Sculptor). © Ann Zelle

AZ: Final thoughts. Well, you’ve mentioned that there are people [in the community who have a negative reaction], either for the research you’re doing or for the exhibition at Hull House [Report to the Public], that there’s a reluctance to glorify a street gang, because there are gangs today, and they do bad things, and kids are tempted to be in them, and sometimes forced to be in them, I’m sure. But, I think there’s such a wonderful lesson there. Just that young people in a community, in a range of ages, not just kids, but the older people and the young people together can make something good happen, even when they don’t have money, they don’t necessarily have education, but the power of community and they have the community, they’ve already got the group, they’ve got the gang. And if that lesson could be an inspiration to them to do something good with it, then I think that’s really worth trying to get across. It’s really kind of a miracle thing that happened there, when you think about it. You think, “How did that happen? How were those guys, with all they’d been through already, how were they smart enough and wise enough to get the discipline and the respect and everything else to pull that together?” I don’t know. But it can be done, evidently, cause they did it. So, yeah, I’d like to see it happen again.