Arlene Turner-Crawford is a Chicago-based artist committed to community and activism. She works in a range of media including painting, assemblage and collage, drawing, graphic design, and illustration. Her work informed by the works of AfriCOBRA artists and black classical music (jazz), as well as her own family, research, and meditation. Crawford earned her BS in education from Northern Illinois University and was the first African American to earn a MS in art education from Indiana University’s Herron School of Art. Crawford has served on the Executive Board of the African American Arts Alliance, and was a founding member of the Sutherland Community Arts Initiative and Sapphire & Crystals, a collective of African American women artists. Crawford’s work has been exhibited in Chicago at the Chicago Cultural Center, ARC Gallery, South Shore Cultural Center, African American Cultural Center at the University of Illinois at Chicago, Creative Arts Foundation and Malcolm X Community College President’s Gallery, National Museum of Mexican Art, and at the Evanston Art Center, National Conference of Artist, Fundacao Cultural do Estoado de Bahia, Salvador, Brazil. She was interviewed by Rebecca Zorach in June 2012.

Rebecca Zorach: You studied with some of the members of AfriCOBRA—can you tell me about that?

Arlene Turner Crawford: Yes. This is a silkscreen that Nelson Stevens did; I was the model. I used to model for his drawing classes. When Nelson first came to Northern, I was modeling for the art department. It was my work-study job.

RZ: And you weren’t an artist yet at that point?

ATC: I was an art major and he started hiring me to model for his drawing classes, which was cool.

Early on AfriCOBRA members created prints; their concept was to make affordable art. Each member had to design a print, which could be mass-produced, either as a fine-art print or a silkscreen print making it affordable for the community. They sold them for $25 or $50, something like that. That’s when I got these pieces.

Jeff Donaldson taught for a little while at the Carruthers Center for Inner City Studies of Northeastern Illinois University. His office was next to mine; he gave me a couple of prints then. When I was in high school, Murry DePillars completed his student teaching work at my high school. This is how I came to know some of the AfriCOBRA artists.

RZ: What was your high school?

ATC: Harlan.

RZ: Wow! I just spent a year teaching art history there, one class period a week.

ATC: Oh great, I love it! Yes, that’s my alma mater. It was a really fertile place, at least that’s what I thought at the time. Looking back on it, there were a lot of people who went through Harlan.

RZ: So Murry DePillars was your art teacher there…And did you go straight to Northern after high school?

ATC: Actually, I started college at UIC. My brother was going to Northern at the time. My parents couldn’t afford to send both of us away. I got admitted into the Art and Architecture cohort. UIC was on quarters; the incoming Art and Architecture students took foundation courses together. I did my first year there, and then my brother, who was majoring in pre-pharmacy, needed to leave Northern, he was going into his Junior year, he needed to come back to go to U of I for their pharmacy college. So we switched schools and I got the chance to go away from my parents, that’s when I went to Northern in my sophomore year.

RZ: So you were an art major from the start there?

ATC: Yes. I graduated high school in ’66, and I started at Northern in fall of ’67. There were maybe two Black students in the art department there, at that time. A brother named Alfred and me—I still keep in touch with him, too.

RZ: Were there very many Black students in general at Northern?

ATC: At that time there might have been about 300 Black students in a school population of 8000. There was a program, the Chance Program, although I wasn’t a part of it—it was a program that recruited students. I guess it was one of the first federally funded programs that recruited first-generation minority students to go to college. I knew about Northern because my brother went there, I had visited there a couple of times. I thought of going to Northern, because it was close. The Chance Program was there, so there was a Black population, we all knew each other.

RZ: And were you very politicized, at that point?

ATC: Ah, I was politicized a bit in high school because of people like Murry DePillars and issues going on at Harlan; but even more so at Northern. Especially after Nelson came there. I was in the art department, not really relating to a lot of what was going on in the art department, thinking, “maybe I shouldn’t be here, maybe I should be doing some other things.” This was in the middle of the ’60s and all the stuff that was going on. When I was at Northern, King was assassinated. I saw that there were many issues on campus, the Black students took action; I participated in a sit-in, in the NIU’s administration building, to protest the fact that NIU had few Black faculty and staff that were counseling or relating to us. Although the Chance Program existed and it had a group of advisors, faculty advisors, for students, Northern still had other Black students in the general population that might not, or didn’t necessarily have that kind of support from the general university community. Like I say, in the Art department it was me, I was the only Black female in my class in the art department at the time. (Freida High [later Tesfagiorgis] was the first Black woman to be a student in the department; she graduated in 1968.) There was Alfred but we didn’t have a whole lot of classes together, so I was always in that situation in most of my classes of being the only Black. There might have been one or two black students in a large lecture class, maybe there were a couple other Black students in some of my other classes, but for the most part, the school was in the cornfields of DeKalb. Black people were a new thing to that institution, so to speak.

There were a few conflicts on campus. We protested, we had a rally at the Bell of Victory on the campus grounds, to discussed a take over of the administration building, Altgeld Hall. As NIU acted to answer our demands, the school brought some new faculty in. In fact, two of the faculty members that were recruited were for the Art department. I don’t know how that happened, but it did. Grace Hampton-Porter, and Nelson Stevens. It was deep, because I was taking a printmaking class the semester Nelson toured the campus. I’ve forgotten my printmaking instructor’s name, but I was working on some print process, when I see this brother with a cute Afro and I’m like, “who is that?!” Professor Ben Mahmoud, who was also a printmaker, was showing Nelson around. I knew Mahmoud although he wasn’t my teacher; I asked Mahmoud, “who is this?” He couldn’t answer me then, so I’m running around, trying to find out who the cute brother is. I found out he’s supposed to be working in the Art department in the next semester. I said, “What! Okay, that’s cool!” When Nelson came, Mahmoud actually introduced me to him. “I’m so glad to hear you’re going to be coming to teach in our department and I’ll be trying to connect with you!” Nelson was happy to meet some Black students.

I took his drawing class that next semester. I had both him and Grace Porter; she came to work in Art Education department while Nelson came to the Studio division. He taught painting, drawing and an African-American art history class. So I probably took all of his drawing classes, I didn’t take his painting classes, but I took his art history class. And then I took Grace’s classes, throughout the last two years I was at NIU.

RZ: So, and before they came, had you felt a disconnect with what was going on in art circles?

ATC: Yes. I was trying to find subject matter, you know. And I wasn’t really relating to the kind of things I saw my peers working on. At the time, what was big was cows. And I understood cows on one level, ’cause we were in the cornfields, and there were a lot of farmers! There was the holy cow, the symbol of the cow at that time, and that was one of the things I would be talking about. I wasn’t moved by that kind of subject matter. I’d work on my skills in drawing, but when it came to trying to develop a concept or a theme or something like that, I wasn’t feeling what they were doing around me. I was kind of at a loss to think about what I wanted to produce. Again, at the time, so much was happening in the Civil Rights arena, that really why do I even need to be an artist? Because they’re not, you know, Black people don’t collect art! I was really having some internal issues about moving forward as an artist, because I didn’t think I’d be doing anything relevant.

I took Nelson’s African-American art history class, because he was saying, “that was one of the things the department hired me for.” They didn’t have anyone to teach that kind of curriculum, until they hired him. He had a really exciting class, and when he first came to Northern, he’d come into Chicago a lot to connect with the arts scene there. He was originally from New York, but he was coming to NIU from Kent State, where he had just finished his master’s degree. Chicago was the big city he was connecting with, and he met Jeff Donaldson. In Nelson’s art history class, that semester, during the Fall term, for an assignment, everyone in the class had to meet, talk to, and interview a Black artist while home for Christmas break. You have to find a Black artist to complete the assignment. He said, “Oh, Arlene, I’m going to have you interview Jeff Donaldson.” I said, “okay, I’ll do that.” So he set it up, for me to go meet Jeff Donaldson. I came home for Christmas break, and called the brother. I said, “I’m in Nelson Steven’s class, he’s asked us to interview a Black artist over our break and write a report, so, can I do that?” And he says, “Sure, you can come over.” Meeting him changed my life, it really did. He showed me my purpose. He talked about art and the mission of Black artists and why our communities needed them and what they had to do and where our niche needs to be. He talked about how as a Black person, I didn’t really need to become reactionary about what was going on, I needed to move forward and be positive, and identify my goals. Identify my goals as an artist or as a Black person, and not accept a Jim Crow mentality. That was also how I was raised to think anyway, to feel free to Be and Do. However things were different, there was so much conflict around that I was exposed to. Jeff’s words really made things so much clearer to me. I can come up with themes or ideas that would elevate Black people. I don’t know if it was AfriCOBRA’s concept or Nelson’s or the kind of ideas I just kept my mind on, Black art needed to record, identify, and direct. So whenever I create, I can either record something about my community, or the life or the history of Black people, their lives and my community; or identify values, or some idea or some event that needed to be brought to mind; or direct people to a higher consciousness about themselves or their community. That would be easy for me to do!

Jeff also invited me to participate in ConFABA…

RZ: I wanted to ask you about that!

ATC: Yes, which was another great experience, it was like that the whole school year, it was really, really…a dynamic year for me. I went to ConFABA, the Conference on the Functional Aspects of Black Art, which happened during spring break or our Easter weekend. I was one of the student members of the Education Taskforce. There were seven different taskforces that were basically developing a manifesto. It’s the first time—I didn’t meet her—but Elizabeth Catlett spoke to our group via phone, a conference call. She was denied her visa, at the time, and she was going to be one of the important speakers at the conference, but she wasn’t allowed to leave Mexico to come because of her political involvement. But she spoke; we were all gathered around this speakerphone! And there had to have been at least 200 or 300 people.

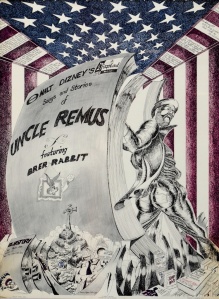

I met Barry Gaither, David Driskell, that weekend. Nelson had already been involved in the National Conference of Artists. Just from growing up in Chicago I had already known Margaret Burroughs and some of those people. I started going to NCA conferences after attending ConFABA. I had an opportunity to met Lois Mailou Jones, Samella Lewis, all these people were at ConFABA. I’m sitting on a committee and able to have my own input, because our task force was charged with identifying a goal and purpose and an outline—or a manifesto, so to speak—for the education of black children with art. I teach a drawing class now and I talk about what art does, or the three things that drawing does. It records what is seen, visualizes what is imagined, and symbolizes an idea. That was how I talked to my students about drawing, but back then, we were saying, “What kinds of things are we going to direct our children to do?” It was then when, were we’re talking about that; “…we need to record, identify and direct.” We don’t need to be directing them to be picking up any necessarily violence or negative things, but try to keep ideas positive, so they can see what is beautiful in their own culture, or what’s important in their family and identify their values, and that kind of thing. We had to start getting away from the Mickey Mouse kinds of art projects that really aren’t trying to move kids into taking themselves seriously, or their own expression seriously. I felt I contributed to this, when they used, a sentence that I came up with, actually put it in as part of the paper we were all working on. I felt, “wow! Oh cool … I’m not an idiot!” It really helped my self-confidence. On the taskforce, everyone there was interacting with the students; they were taking time to talk to us, to hear what we had to say. I met Tom Feelings; I was meeting all of the people I was studying in Nelson’s class! Jacob Lawrence wasn’t there but I eventually came to know him through NCA, and that just really changed me. You know, it changed my whole outlook about what I wanted to do.

RZ: Was that manifesto published anywhere?

ATC: It was, you know, it got published we all received a copy of it, and in fact I probably have mine somewhere around here. The last time I had it out was when I worked with Patric McCoy on “Taller than Most” [a 2004 tribute to Jeff Donaldson]. And I pulled it out, I found it, I made copies for everybody that I worked with in Diaspora Rhythms and I probably filed it again. There were other taskforces—there was a philosophy, an education, marketing and history.

RZ: Sure. And about Margaret Burroughs, when did you first meet her?

ATC: Oh, I met Margaret Burroughs when I was in third grade. My third grade art teacher was a good friend of my grandmother, they were buddies, I think my grandmother did her hair. She knew Margaret Burroughs, she thought, at third grade, she’s like this little art kid, you know, she’s interested in art and I think she’d like to meet her. So she actually brought Margaret Burroughs to my grandmother’s house to meet me. Margaret Burroughs shook my hand, and said, “oh, you like art?” and even then she was really engaging. She told me, I remember she told me, “visualize myself as an artist. In fact, visualize yourself as anything you want to be.” I told her, “I’m a third grader,” and she says, “are you interested in art?” “Yeah, yeah, I like art.” My teacher, May Banks, said, “yeah, she’s pretty good, I like her work and in class she’s very focused and things like that.” And Margaret said, “well, anything you want to be, starting seeing yourself doing it, start dreaming about it, start visualizing yourself doing it.”

I remembered that. Then I would see her from time to time, I’d go to the DuSable Museum, with my school class — at the time, it was in her home. Throughout elementary school, from time to time, I would see her, either some teacher I had or some group would take us to her home to see the first DuSable Museum, and I really started early on, knowing about the South Side Community Art Center. I must have visited there, throughout 8th grade and all through high school. So, later when I joined NCA, Margaret remembered me—well, I believed she remembered me, but I always was to “aw yeah, I know this woman.” [laughs]. She eventually knew me to say “Arlene.” “Hey, Arty.”

In 1982, I was a member of NCA, the Chicago chapter, and Chicago was to hosted the 25th anniversary conference the next year. I was Chair of the Conference Planning committee. In fact, I was one of the Vice Presidents of the chapter, Adjoa Burrowes was President. Together we’d sit around Margaret’s kitchen table and discussed the plans, as we were putting the conference together. I really got to know Margaret better, as a peer. She had to assign me tasks and things like that! It was a very busy time.

RZ: When did you join the National Conference of Artists?

ATC: Oh, when Nelson came to Northern, probably back in, what year was that? I started Northern in ’67, I think by ’68, Nelson was there and influenced me to join NCA. I started going to the conferences as a student, then for the next 10 years, I was at every conference I could afford to get to; both when I was an undergrad student and a graduate student, I would go to the conferences. After that I would try to make it whenever I could. Nelson helped me, be admitted into U Mass in Amherst for graduate school because by then he was teaching there.

RZ: So he moved there from…

ATC: Yeah, he moved to Amherst from DeKalb when he got a position at the University of Massachusetts. He said, “Arlene, you got to come out and do some graduate work.” After I finished my undergrad, I worked for about a year and a half. By then Nelson was at UMass and I was able to consider doing some graduate work in art. He helped get me admitted on a probationary status. I went there for about a year. I had some problems; I had a nervous breakdown! It was very competitive at UMass. I was away for home and very lonely. It was probably the first time I had ever been that far away from Chicago and home in my life. I ended up leaving school, getting married and moved to Indianapolis with my husband, Richard Crawford. When we eventually moved back to Chicago, I got back involved in NCA. It was good.

RZ: I’m wondering about all the political turmoil of the ’60s and ’70s. Did this raise the question for you of whether you should continue to be an artist in those conditions, or to be militant in a different way? I’m curious about the choice to continue, it seems like it was really important to you to have someone like, people like Nelson Stevens and Jeff Donaldson, to point a way to be an artist and feel like your art was having an impact. Can you say a little bit more about that?

ATC: I became exposed to and met most of those artists, writers and playwrights who were, at that time, basically the vanguard of the civil rights movement. They were the ones making, rather bringing a lot of attention to the values and the issues that were going on. Students were involved too.

When I was in high school I was a member of Trinity United Church, at that time a brother named Rev. Kenneth B. Smith was the pastor. It was my church; it wasn’t a big church like it is now. Trinity was housed in a grammar school, in fact, when it first started out. Reverend Smith was a member of the Southern Christian Leadership Council, and when the students (I, myself was in high school at the time) those college students were going down south, taking those bus rides to go help register voters, and were being beat up and attacked that kind of way, Rev. Smith was there. He was bringing these stories back to our church. I was a member; along with my brother, in the young people’s Christian Fellowship group there. Thanks to Rev. Smith, who was a member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, he kept us informed about what was going on in the South so that we wouldn’t become—again, reactionary and angry—but to be able to think about things in a way where you would be proactive, where we were making some positive steps to bring issues to the front and try and create a way to discuss them and to talk about them with other people.

One of the things Reverend Smith was doing at the time was having the Christian Fellowship members spend weekends with white families in the suburbs, so that we could begin to get to know each other personally, on a different level, and they could get to know us on a different level. I had these kinds of activities going on when I was in high school. When I got to Northern and all the things that were happening with the civil rights movement, with the marches, the protests around the country, the killings and the bombing of those four girls in Alabama—I witnessed these things. I would see it all on television, and it would make me angry and it would make me want to talk about it with my parents. “What’s going on? Why is this happening?” I hadn’t grown up in an environment where I thought that there was any difference between a white person and me. We were the same, you know. There might not have been many of white students in my high school, but there were some in my high school, when I started as a freshman. I had had experiences in elementary school because I went to at the time, a primarily white elementary school in Roseland. Even though there would be, kids that would say bad things or talk about us, it never really affected me or made me feel in any way not as privileged as them! In some way, so I was growing up with this mentality that there wasn’t anything that I was not capable of doing, nothing that could limit me. But that wasn’t really reality, you know? And by the time I got to college, I had started meeting other artists, and because I was interested in art, I was also interested in theatre and reading books. And all of the writers and poets and other people who were the vanguard of this movement, who were trying to elevate the issues and create art, create plays, create books, poems that addressed the issues. I wanted to be there. I wanted to be a part of that; I wanted to be, “yeah, I can do this.” I can at least, support it, help it out, or validate it with my presence.

RZ: So, it actually, it sounds like it actually just felt really natural to be an artist, like, that artists were kind of the vanguard of political activity in a way.

ATC: Yes. And that’s what Jeff was telling me, and everything that I gleaned from ConFABA, meeting all those people, and there were some interesting people, because ConFABA brought together not just visual artists, but writers, poets, playwrights. Back then I met Don L. Lee, who also came to Northern several times, before he became Haki Madhubuti. I met LeRoi Jones, before he became Amiri Baraka! So, I was meeting playwrights of that caliber, who were also very political. I was going to hear lectures, I was being political, as well as trying to find something to paint about, or something to draw about, or some issues I could turn into artwork. So I could do something.

RZ: And as an artist, have you always identified as a painter? Because you have prints and…

ATC: No, mainly I started drawing, it was my first love, but who draws? Nobody respects that! [laughs] I, so I have been trying to identify myself as a painter, as a mixed-media artist person, doing collages, painting, drawing and collage. I started UMass as a printmaking major, I think probably because Nelson was a printmaking major when he was in undergrad. And then I ended up finishing with a degree in Art Education. I completed my undergraduate degree in Art Education, because my mother said, “you better get a degree in Education! You can’t just be an artist! First off, you’re a woman! Second off…you need a career, you need something you can fall back on!” So I agreed and followed her advice.

RZ: And then did you teach?

ATC: Yeah, I did.

RZ: Right away?

ATC: Yes I taught, but not art. Initially, I taught, in an elementary school as a substitute, that’s how I started teaching. At the time when I graduated, the city wasn’t certifying any new Art teachers! I had taken the test to become certified to become an Art teacher, and I passed, but CPS had no new positions in art—“we got a whole drawer full of them.” So I started subbing, and I got a couple of positions from subbing. I got a classroom in kind of a middle school position, before middle school was a separate thing. I was teaching 6th grade. Language Arts was my assigned departmental thing. The school administrator felt I could teach English, even thought my degree was in Art. I was also good at math, so I taught departmental English and some math. Funny, my daughter is now a middle school-endorsed teacher. She started college as a communications major, TV and radio. She’s an excellent writer, and while she was at Howard—she went to Howard—and she started tutoring, a work-study job and fell in love with teaching. So when she got out of Howard, she said, “I don’t want to go into TV and radio, I want to teach.” So she went back and got a Master’s degree in Education with an elementary and middle school endorsement. I laughed and told her, “That’s what I did when I first started, and I know you don’t want to be like me!” She did say “No, I don’t!”

RZ: And when did you do your first mural?

ATC: I did my first mural in Indianapolis. I worked for the Girl Scouts at the time, in my position as a Program Executive; I was loaned to a program at Arsenal Tech High School. Jimmy Carter was President then and his administration created CETA monies going into various inner-city communities across the country. Some of these CETA funds focused on trying to help classroom teachers by offering other support services to the students. The Arsenal Tech CETA program had a cohort of 300 freshman students when it started. Arsenal Tech High School was a huge technical high school in Indianapolis. Within the program there were 10 classes of 30 students; the program called them “Families”. There was an overall Supervisor, a Reading specialist, a Social worker, and someone for Programmatic recreation. The program contracted with Girl Scouts as well as Boy Scouts, 4H, Boys and Girls Clubs and other such agencies, to provide staff to work with students programmatically. So to make a short story long, that’s when I did my mural. The first summer of the program they had various activities where the recreation person got to be in charge. During the year we were doing some field trips and mentoring activities with them. I was working on my Masters degree in Art education at Indiana University, and commuting back to and forth to Indianapolis at the time. The program had an opportunity to do a set of murals in the downtown Indianapolis area. Our program had hired a professional mural artist from Germany. He was supposed to work with the group. I said, “Oh, I’m an artist, I’d like to volunteer to work with this!” The German artist ended up not really being able to do the project, he had another commitment that took him out of the country. So, I ended up in charge. We had six areas to paint that were outside, on this railroad overpass. We needed to design some kind of murals for the spaces. All the paint was contributed, the German artist had arranged for it before he left, he basically had set up most of the logistics and had gotten the paint, supplies and everything. He had completed one workshop with the students and me; and in it we designed six different mural, I got to design one all by myself.

Mine was red, black, and green, with a black strip that came up 4 feet off the ground, each foot was to represented a hundred years of oppression in America. The site of the murals was right across the street from the city jail. So I was decided I wanted to do these pyramids—that’s what I came up with. That was my concept. We had six weeks to do six murals. We completed a mural a week but we really worked on all of them at the same time. We finished them all in that summer program. It was fun. I was pregnant at the time! So that was interesting, out there working that summer, it would get hot on the walls; we would work from early in the morning, from like 7am to 2 in the afternoon. Trying to finish before it got really too hot, especially for me. We built our own little scaffolding, and maybe it was about 12, 13 kids on the project and another couple of counselors and myself. It was a nice experience.

RZ: Did that have a title?

ATC: We just called it the CETA murals (City Walls). I don’t think they’re there anymore. I tried looking for them, the last time I drove through Indianapolis.

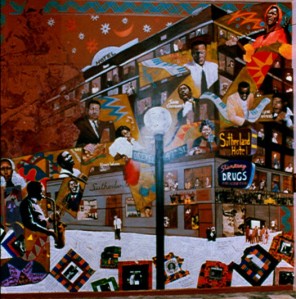

I did the mural at the Sutherland, that’s an interior mural. Then I worked with Kiela Smith-Upton on the Sutherland mural and on a mural at Phoebe Hurst Elementary School. And I’m doing this Bronzeville mural now, but I’ve done some projects with other artists. I worked with Nelson on a mural, I coordinated a mural project for NCA when it’s 25th anniversary conference was in Chicago. My kids were going to Haki Madhubuti’s school, New Concept Development Center (NCDC). I wrote a grant and got funded to do a mural while the conference participants were in town, for the conference. They donated their time and did a mural for the school. I did a little work on that but not a lot.

RZ: I’m curious about the different media that you work in: drawing, painting, printmaking, and mural painting. Do you see them differently as forms of expression?

ATC: No, I don’t. I just try to find what I think would be the best way to present an idea. When I first started here, I was just trying to become a better painter, and so I would do more painting, but I think as I wanted to branch out, part of me is always wanting to find some way to grow, so I’d try different combinations, different media. Like, the show I’m doing with Sapphire and Crystals, we’re doing an exhibit at WomanMade Gallery, in October, for Chicago Artist Month, and the theme is State of G/Race, where it’s kind of a play on “race” and “grace.” I’m trying to construct these crosses, this is a little sculptural, the idea I have came from when I went to see “Fela.” I was struck by, at the end of the play when the players put these coffins on the staircase of the President’s office building. That’s when it struck me, I said “oh, now I know what I’m going to do for State of Grace! I want to take some kind of imagery and assert some values, assert some positive values.” At first I was thinking, maybe I’ll try and bury some negative ideas, but then I thought, no, I want to promote some positive ideas. So I’m going to make these crosses and then try and find either poems or sayings or words that assert either a value or some kind of idea that can help move the race forward. Something simply, like, “work together,” “trust one another,” or “pull someone else up along with you.” Just to bring home the idea that spiritually, we’re connected. That’s why, I was like, “oh, yeah, I can do that.” And this is my other idea, this church window. I went to Brother Hannibal Afrik’s funeral; he was an activist and an educator, a part of the Nationalist community my children grew up in. He was the founder of the Shule Ya Watoto, which was an Independent school on the westside of Chicago. When he passed away, I went to his funeral, and was drawing this window in his church, on a fan. Posted in his church was this saying in this church, “Where there is no vision the people perish”. The saying also made me think about the Grace idea, and the state of race and grace. I thought that’s a very powerful proverb. It’s Proverbs 29:18. So now I’m doing a little research to find some strong religious texts that could assert some positive ideas. I think that would speak to the state of grace. Or the state of race!

Arlene Turner-Crawford, Proverbs 29:18 (2012). Linoleum cut print and collage, 28 x 24 inches. Exhibited at WomanMade Gallery, “State of G/Race”

RZ: Have you been part of Sapphire and Crystals from the beginning? As a founder?

ATC: Yes well, I’ll put it this way. Marva Jolly and Felicia Grant-Preston are the two founders of record, but I have been a member since the very first gathering, when we came together and named the organization. And that’s also been a labor of love and commitment to me, so that’s nice.

I like that I grew up seeing Nelson and listening to what he and his peers thought about collectives. So when I had an opportunity, when Marva and Felicia invited me to do this, I just jumped at it. I was saying, “Oh, yes! we can be our own Collective! Make a movement.” And it’s been a great experience. I’m glad I’ve stayed consistent with it. We haven’t necessarily ever formalized our organization, because everybody’s busy. But it’s been a great experience.

RZ: It seems like sort of a looser collective than something like AfriCOBRA. In terms of aesthetic principles or philosophy or that kind of thing, are the artists doing more their individual thing, but supporting one another in various ways?

ATC: Mm-hm. When we originally came together, we wanted to be definitely a forum for women artists, and to set it up so we could at create opportunities for women artists to—African-American women artists—to exhibit together, to create venues, and to support each other. We’d bring work together, and ask, “what you think of this?” give each other feedback, but that was about it. We’re not really looking for to get everybody to center in on some aesthetic principles or things like that. When we pull shows together, we usually try to come up with a theme that everyone could embrace, in whatever media they’re working in, it has some flexibility in that. The work I do has been focused in some way to address the African American community, but it’s not really a criterion and it’s not always a theme that we work with. A lot of the women aren’t as political.

RZ: Do you see your work as political?

ATC: Yeah, I do.

RZ: I’m curious about, you talked about the three aims of recording, identifying, and directing? And is there one of those that you identify with most, do you think, or are they really the same?

ATC: Not really. I think I try to do something within one of those ideas, or a combination of them, when I do create. Because that was my first charge, so to speak.

RZ: But those three things are still speaking to you?

ATC: Yeah, they’re still important to me.

RZ: Can you think of an example of some piece of yours that epitomizes one of those three principles?

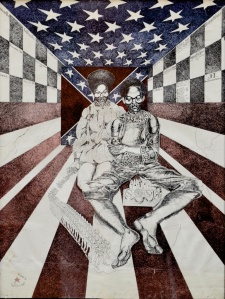

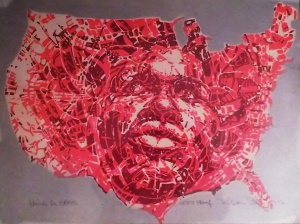

ATC: I like this piece. I did a show, it was a Sapphire and Crystals one, the theme was “Goddesses, Mentors and Other Heroes.” We had the exhibition the year Malcolm X would have been 75, had he lived. So I chose him—we always have to do a self-portrait—so I chose Malcolm to be my mentor, my representation of a mentor. I said to myself, I couldn’t do a picture of Malcolm without using his words. The exhibition also happened the same year as 9/11. So I tried to find some words that I think Malcolm would be able to say, and in terms of addressing what happened during 9/11, I picked this idea. “We as African-Americans, feel receptive towards all people of goodwill. We are not opposed to multiethnic associations in any walk in life. In fact, we have had life experiences which enable us to understand how unfortunate it is when human beings have been set apart.” I thought that, my response to 9/11 was, everybody was talking about terrorism, everybody was polarized, on opposite ends, trying to find people to blame, or to hate. I was thinking, this to me epitomized an idea that Malcolm would put out there; about finding what things human beings have in common; oppression and negative things that happen to set people apart, but we’ve got to get beyond that. We’ve got to.

RZ: Why is he doubled in it? Does that mean something?

ATC: I’m a Gemini. [laughs] Probably, I think, yeah: I’m a Gemini, he’s a mentor, it’s a double kind of thing. That was me pictured as a real young kid in that work, that was when I first read Malcolm, when I was in college. I think that’s what I was thinking about, trying to direct people to some higher ways of dealing with 9/11.

I did this series on music …this is a tribute, my homage to Sister Augusta Savage. And that’s the music in three-part harmony. I’m doing a series on music, I call it “Check the Blues Out Before School’s Out”. Within this series I’m trying to demonstrate my process, when I go to hear music live, I write and do little sketches. So I’m taking these sketches and turning them into compositions, trying to put the writing with it. I’m basically trying to identify ideas about Black music in them, and record the moments here.

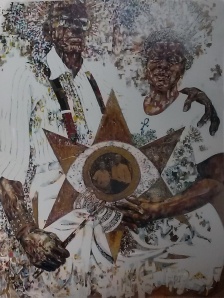

This is my piece I call actually a friend of mine named this. I said, “What can I title this?” This is a portrait of my best friend, a dancer, who passed away. I had done a mask of her one time when she visited me, so I did this piece in honor of her. My friend, who I had asked said, “you should call it “The Burning Knowledge of Our Ancestors”. This is an African medallion that represents a secret society of the EDAN people. The society members are responsible for the political integrity of the community. Patty O’Neal was a dancer and she was very staunch political person. She had been adopted, part white, part black, but she had been raised by Black parents and had a consciousness that just wouldn’t let up. Her dance work was always about promoting justice. There is Kemetic symbolism in the work; the vulture is a Kemetic symbol of motherhood. It’s a powerful symbol of motherhood and nurturing because the Kemetic people observed how vultures care for their young. The text behind the image comes out of the book of Osiris. It’s a combination of things that I was trying to pull together in order to honor my friend Patty when she passed away. This is another portrait of Patty, because she kind of looked Egyptian, that’s why I put the hieroglyphs in it. Patty was an avid reader as well. I wanted to combine the consciousness that, you know, the light at our feet is: all we have to do is read! These are some of the books that I think you should check out. I wanted to record some of my library, things that have stimulated my ideas.

I’m trying to get about 30 pieces that have to do with music, and then I’ll have a show. I do a few at a time. I’m getting them together.

I also have a series I called “The Cosmic Community.” I actually had about 12 pieces in this series. This was the centerpiece of it; it is called “Earth, Ether and Light” and it was about what’s in the ether, what’s in our energy.

RZ: When you put text in your work, do you think about AfriCOBRA using text?

ATC: Yes, because their method was, if you want something to communicate, put some text in there. You can write, you can say what it is. Actually, as I was coming up, that was a lot of what was going on, especially with a lot of my peers. I love it when I see that in other arenas, not just in AfriCOBRA but other artists, using that straightforward means of communicating. Write it! I tell my students that, “if you have something to say, put it out there.”

RZ: And then another question: Romare Bearden. Is he important for you?

ATC: Yes, very much so! I started looking at collages and I love his collages. My friend Patty’s mother and father knew Romare Bearden, they have a Bearden in their house, the first original Bearden work I saw in life was the little one that Patty had. I saw it when I first visited her in New York. I had followed him, and I thought he’s a excellent collage artist. This was my piece I was trying to really get into collage. This was one of my first collages that I did. I had completed the drawing and then I said, “let me put this guy somewhere”. I created this landscape, collaged it.

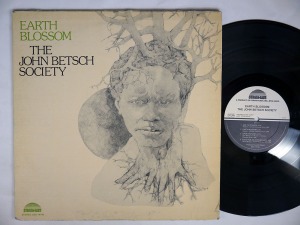

I did this in graduate school. It was a Nelson assignment; he had us create our idea of a “cosmic space child”. I had taken a picture of Nelson’s hands, and I drew his hands as part of this drawing. I had an affinity for trees and actually, it work became an album cover for a friend of mine. The album is called, “Earth Blossom” the John Betsch Society. This work was completed in the 70s; I did this in ’73. John Betsch is a drummer who was studying with Max Roach at UMass when I was doing graduate work. It was his first solo album, he said, “I’d like to use this for the album cover!” and I went, “yeah!” I didn’t get a dime, but I didn’t care. The album was produced on Strata East label. The label is now defunct but it’s a classic label in Jazz, but you can’t get music from Strata East now, so the album itself is a collectible. That’s my little glory history. The collage over there was for an exhibition with Sapphire and Crystals, we called it “Meditation on Race and Women,” it was my meditation on race and women and I came up with that composition. It’s about identity. I used collage to make a prototype Sister.