Homocore Chicago was started in 1992 by Joanna Brown and Mark Freitas to create a space for queer punks to hang out and listen to live music, mainly queercore and feminist punk. This interview was conducted in August of 2011, ten years after the last Homocore show happened in 2001 featuring the band Le Tigre. Check out their archive page on Facebook. The Photos in this interview were taken from the Queer Zine Archive Project and the Q-ZAP Photo Archive.

Daniel Tucker (DT): Let’s start with the prehistory of your work together, and then we’ll get into what actually happened with Homocore and then what has been going on since.What kinds of groups or communities were you a part of in the late 80s, early 90s before Homocore started?

Joanna Brown (JB): When I first moved here I was involved in some activism, and then that went into ACT UP, and Queer Nation, a little bit, and Clinic Defense, stuff like that.

Mark Freitas (MF): and I was doing similar kinds of stuff, in the Detroit area, Ann Arbor specifically. I was also involved in a lot of radio stuff, I did a Queer radio show and they did a Feminist radio show, I co-produced each of those, and would occasionally engineer on one of the pro-Palestine shows. So, outside of that, I was just generally kind of a little industrial punk kid that was running around making music, and enjoying what turned out to be the Detroit techno scene, although at the time we didn’t realize it was all that. We were envious of the rest of the world, that they had all this great music and we just had out own little local techno scene, whatever techno was. But it turned out we were in the right place and just didn’t know it. So yeah, and I had been in touch with some folks in Toronto, cause I was in the punk scene and I was queer, kinda coming out, and doing a lot of the AIDS activism, and didn’t seem like the two worlds meeting.

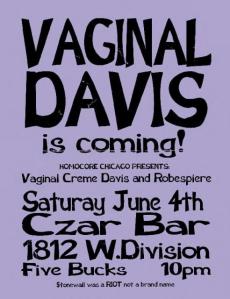

But I was kinda saying, “gosh, someone’s gotta be doing this,” and somebody said “yeah, there’s these people in Toronto, G.B. Jones and Bruce laBruce” and so I started scouring my Maximum Rock n’ Roll issues and they’d put a little something in there, some little notice in there, so I wrote to G.B. Jones, and she told me, “hey, come to Toronto, come visit, come be in a movie! We’re doing a spring film festival!” which was basically them showing all of their little 8mm films. And so I went up, I said, “sure, I’ll go to Toronto,” and I hopped on the train from Detroit to Toronto and got to meet all those folks. They turned me on to Vaginal Davis, and also on to this gentleman Steve LaFreniere, who was doing a zine in Chicago. And Steve will turn out to be very important when we talk about SPEW, because even though there were a bunch of organizers, Steve LaFreniere was kind of the kingpin. He did a zine called The Gentlewomen of Southern California, I believe?

JB: I didn’t even know about the stuff that G.B. and Bruce were doing, until SPEW. I had been looking for it, and I had seen a couple issues of the Homocore zine, put out in San Francisco.

JB: I didn’t even know about the stuff that G.B. and Bruce were doing, until SPEW. I had been looking for it, and I had seen a couple issues of the Homocore zine, put out in San Francisco.

MF: And actually, I had written to Tom and Deke first, saying, “hey, I heard there’s this zine,” cause the letter’s actually in issue #3 or 4 of Homocore zine, but I mean I hadn’t really met anyone until I went to Toronto. And then they told me, hey there’s this whole thing going on, so I got hooked into all these people. There was also Larry Bob, I should mention, who was there from the very beginning, he’s really first generation of the queer zine thing, along with JD’s from Toronto and Fertile Latoya Jackson, out of the Valley, which Vaginal Davis did, that was kind of the first wave of the queer zine thing.

We had all been writing, at least on my side, we had all been writing letters to each other forever, cause that’s what we did before everyone was on the internets…

JB: Well see, I was desperately looking for that, because I was lost in this sea of disco-loving homos, and I had my little Sonic Youth records and I’m like “I can’t be the only one!”

DT: And what were the Queer activist scenes like, in terms of culture and music in your experience?

JB: Here in Chicago I was really miserable. It was Carolyn and I, and that’s one of the reasons we’ve been together for twenty-one years, because she’s the only girl I know with, I mean, the musical taste was horrible, it was nothing but disco. Except for like Steve LaFreniere and Michael Thompson. The rest of them were all thrilled that George Michael might be gay!

MF: In Michigan, it was like, a lot of radical fairy, which I really love and appreciate, a lot of old school anarchist commie kind of 60s politics, SDS was alive and well, and still alive at University of Michigan in the late 80s. So there’s a lot of hangover from the 60s, but in terms of the kind of the more punky, anarchist politics, where they existed, they still had that kinda heavy granola flavor. And then the music scene, I mean this was like Madonna and Stockhausen, Aiken Waterman kind of time period, so if you loved Rick Astley, we had places for you to go.

JB: Yeah, I mean, even the queer scene, the queer activist scene was all the disco queers. Nothing but dance music.

MF: I mean I literally had a war on WCBN FM Radio in Ann Arbor, cause I was always playing all this kind of, there’s a kind of long running thread of queer in punk, you know, by Joan Jet, the Buzzcocks doing very Queer-inflected punk rock, and I would play this stuff on the radio show. But half the rest of the staff on the radio show would get really mad, and actually would even come on after I’d played the song and just start ranting on the air, and I’m like, I don’t turn down your Barry Manilow medley, so please.

DT: So, what happened at SPEW in ’91? I’m wondering what was unique about it, how did it kind of change the shape of the queer community in Chicago, who knew each other, who was talking to who?

JB: My girlfriend read an article about it in the Reader, a small blurb, and it said they needed volunteers, and she said, “okay, we’re going to do this.” And we went, and all of a sudden, I’m going through these people’s zines, and there are people who write zines like Donna Dresch way before Team Dresch, Miss Davis, and I was just like, “where’s this been all my life?” you know. I kinda knew something about Riot Grrrl, but not a lot. And it was an answer to a prayer.

MF: had Riot Grrrl even really gotten going then?

JB: I knew one, Riot Grrrl was starting…

MF: That was like the very first year for Riot, this was May of ’91, Riot Grrrl was brand new too, it really was.

JB: Yeah, but the band Bikini Kill was already playing.

MF: There was this massive explosion in the early nineties, of this very kind of radical left-wing sexual politics, feminist politics, queer politics, where people kind of took the old school approaches and kind of reinvented them. And I think what was exciting about SPEW was that there were a lot of us, and we were all disconnected, but everyone did these things called zines. It was kind of an artform, it was kind of a way of communicating, it was a calling card, but it was a way for people to say: “this is who I am. This is what I’m about, this is how I’m different from everybody else, and hey, is anyone else out there like me?” and we would create like a few hundred of these, and read magazines like Factsheet Five and try to find other people that were similarly interested, and send them the zines and trade back and forth. You’d get reviewed and people would write to you because they liked what they read in the little review in Factsheet Five or in someone else’s zine, and it was start pulling people together. And this is, sounds really quaint and stupid now, cause we have the internet, and we have all these things that connect people, in all these wonderful ways, but back then, being a minority within a minority within a minority…

JB: Right.

MF: And having you know these very strange views, to be able to find other people like yourself, that’s really a wonderful thing. And to have this really great form of creating an object that expressed who you were, was really wonderful. So we were all writing to each other, all across the country, I was making trips to Canada to see some of the people I had connected with, like Bruce and G.B., and to hear that, hey, everyone’s getting together, from all over the country, everyone’s flying to be in Chicago, in one place, at the same time, was kind of amazing. You know and you had Vaginal Davis coming in from LA, you had Donna Dresch coming in from, was she in…

JB: D.C., I think.

MF: Was she in D.C. or she in Portland at the time?

JB: She might have still been in Olympia.

MF: Anyways, there’s that weird Olympia-DC connection where people would fly back and forth. You had people coming in from New York, you had people coming in from all over the place, and suddenly all these people met each other and and they got to show not just their zines, but their performance art. You had Ms. Davis and the Fifth Column both doing performances, along with all kinds of other performance. You had people showing off the way they dressed, which you know, the performative aspects of dressing very radically is a very important part of queer culture, I would argue, and something that’s kind of died. The whole, I don’t want to say Club Kid culture, but there was club kid culture that reached out beyond the very narrow definition into a whole way of going out and presenting yourself and really challenging things, just by looking completely different, radically different, the same way that punk did, this kind of way of presenting yourself, and not just drag, but all other kind of modes of looking outrageous in public, were I think, a big kind of statement.

DT: SPEW was taking place at Randolph street gallery, which is really like a well-respected for presenting interesting exhibitions and events, do you have any kind of sense about the connection between the stuff that was happening at SPEW and sort of the larger sort of art activities in Chicago at the time? I mean, was it totally weird that this happened at Randolph Street Gallery?

JB: Oh, no no no no.

MF: I don’t think so.

JB: Randolph Street Gallery was always on the cutting edge.

MF: I mean, the visual art maybe not so much, but frankly, there was a lot of performance art at Randolph Street Gallery. I mean, that’s where I met Ron Athey was he was performing at Randolph Street Gallery, doing some of his extreme body art involving cutting and blood and all kinds of other things that were very transgressive and caused the NEA to have their budget cut one year by about 4%.

They were doing very radical performance art stuff, and a lot of, when you consider folks like Vaginal Davis, and some of the local folks like Larry Steiger, were very tied in with the whole performance art thing, no it made perfect sense at Randolph Street Gallery. I mean, you have people really, I mean, David Sedaris came out of this same scene, people may not realize this, but David Sedaris’ roots were with this same group of queer performance artists that were big in the 80s.

DT: And was there much overlap with that kind of 80s performance art and queer activism?

MF: I think so, mainly because of the AIDS crisis, I mean, it kinda had to happen, the same way that it happened in New York…

JB: Yeah, I mean, everybody around us was dying.

MF: Yeah. There’s like that really great book, uh, Beyond Fear, that talks about the New York scene, I believe it was called Beyond Fear, the way that that whole arts scene was impacted on the Lower East Side by the AIDS epidemic and how the two kinda came, became inseparable, and how AIDS really kind of changed the whole arts scene. Well that certainly happened on the gay male side. And the fact that lesbians really stepped up to the plate and helped gay men, that was a rare moment, really, for the gay movement. Because, today? Fags and dykes do not talk to each other.

JB: Right.

MF: They don’t hang out together, they can’t stand each other. And I’m exaggerating slightly, because certainly there are exceptions, but…

JB: And that also ties in the, what we did later, where that was the most important part of our Homocore shows.

MF: Yeah.

JB: Was the fact that it was men and women, that it was lesbians and gay men, in the same room, at the same time, interacting.

MF: And then we also brought in the all ages aspect as soon as we could, cause that’s a big punk thing, recognizing that not everyone is over 21, and gay culture is built around bar culture, and that kinda of really sucks if you’re under 21, and maybe for previous generations that was okay, cause nobody came out until they were 90, but now! People come out when they’re like, in their early teens. For our generation, high school or college, but still, it’s gotten younger and younger. And in order to accommodate that, and actually give people a way to connect, creating a space like Homocore or even like what happened at Randolph Street Gallery at SPEW. Sadie Benning, who later went on to become an very important filmmaker, visual artist, and a member of Le Tigre, which was a very important band. She, as a teenage girl, was able to come to this space and meet people from all over the world, that were doing work that is every bit as challenging as her own, I think, that couldn’t have, there’s no way that could not have been an important experience for her.

JB: I must have picked up like 40 zines at SPEW, I mean, I just had a stack like this and I spent months and months…I had talked with some of the girls from Fifth Column that night, Beverly Down and everyone, and I kept in touch and I said here’s my address, Jesus I feel like I’m the only dyke here who was interested in any of this. And then they wrote to me and said “well, Fifth Column is touring. Why don’t we come play in Chicago?” and I said, “okay, perfect!” So I call Steve LaFreniere (SPEW organizer), and he said, “oh god, this guy Mark wants to do a queer punk night too. The two of you should just get together.”

DT: Keep going with that and talk about what led to Homocore and what you were trying to achieve with it when you started?

MF: And Joanna and I had kind of met, I had actually stayed at her house…

JB: Yeah.

MF: But it didn’t even occur to me that “oh my god there’s Patty Smith posters up on the wall, there’s all this other stuff, gosh, here is somebody else that is into punk rock just like you and they are coming from the same activist scene, gosh.”

JB: yeah, and so I called you, and kinda explained who I was and I said, “I got this letter from Fifth Column, they wanna tour, Steve said you were looking to put on a queer punk night, why don’t we get together and talk about this, and see if it’s something we might want to do? And if we can work together or not.”

MF: And the place we got together was actually a very important show…

JB: Bikini Kill, at Czar Bar.

MF: And who was opening?

JB: it was Liz Phair’s first public performance.

DT: Nice.

JB: And god she was terrible.

MF: She wasn’t terrible, I thought it was fine. I was just kind of like, “oh, that’s nice.” I thought it was nice.

JB: I never wanted to hear it again.

And I met Kathleen [from Bikini Kill] that night, and I told her, “oh, well, I’m thinking of putting on the Fifth Column show here.” And she’s like, “oh my god, you have to do that, cause that would be so cool, do that! This could turn out to be something really great for you.” I didn’t know her, but she was so, like, reassuring and encouraging.

MF: G.B. Jones was that for me, I mean, G.B. Jones would write me these letters I wish I would have brought some of them, cause they were just completely like “yeah, go boy go.” And that was just kind of what was beautiful about this early scene, and I think, about any scene like this, is like, where people actually go an encourage each other, instead of being competitive about it, until they realize that there’s enough out there for everyone. And that you’re not, you know, taking away anything by helping somebody else or encouraging somebody else.

JB: Right…

MF: And you can actually build something from nothing, if you all do it together., that’s kind of, that was really the feel back then, both with Homocore and Riot Grrrl.

DT: So you two had this meeting at the show, and where did the conversation lead you? What are some highlights of stuff that happened through Homocore?

JB: Well, at first we said let’s just try this one show, and see what happens, so we went back to Czar Bar, on like a Saturday afternoon and said “we wanna do this show on this night,” and they’re like “fine by us, we don’t care.” And we met Elliot Dix who did sound, and then we tried to figure out how to put together a show.

I think that was the first time we, the first and only time we ever paid for turntables.

MF: Yeah, but I think we were worried about renting all the equipment we would need, oh, I think Elliot took care of that, but we had been buying turntables so we could have a DJ…

JB: And we’re trying to learn how to promote ourselves.

MF: Steve, who put on SPEW helped a lot, we’re both saying, “well, gosh, he pulled off this even that got all this press going and whatever else, Steve, how do you do it?” and Steve was like, “well, here, lemme help you out.” And he gave us his mailing list. Who does that, who does that now?

JB: Yeah, well, actually what he did was he went through his address book and said, “okay, write this one down. Write this one down.” And our first mailing was 4 x 6 flyers inside envelopes, hand addressed.

MF: We did that actually for the entire history of the Homocore night, pretty much. We always sent out…

JB: And this before pre-adhesive stamps.

MF: We actually had one of the earliest internet sites, we were listed on yahoo.com back when they would actually handwrite interviews and give you a number of stars for how good your site was. Yahoo used to individually review every site. This was back when the internet was, you know, hundreds of thousands of websites, so they could actually do such a thing. But Homocore was very early on the web.

JB: At the same time, there was a burgeoning youth anarchist movement and we were very tied into that.

MF: We were tied into that and then we would withdraw in horror and then we would jump back in.

JB: Right. They always showed up for the shows. People from the A-Zone…the Autonomous Zone..We started just before they did, and they would all come to the shows, and I’d see them around Wicker Park, and then I talked to a few of them, and they were like, “oh, this is so cool.”, they came to the first night and it went really well, and then we did a couple of DJ nights, and then we decided, let’s start having bands.

MF: Well, Marc Ruvolo, a local figure, was in a band called No Empathy, and did a kind of shocking zine, actually, and that’s saying something for those days. But he kinda said “you know, DJing is cool, but you should put on more live shows.” And we were both kind of scared about the logistics and the promotion and the money and he just kinda said, “look, here’s how you put on a show, it’s not a big deal.” And, um, so we did. What was the next show that we put, what was it, I can’t remember now.

JB: It was No Empathy…

MF: Yeah, it was Marc’s band.

JB: And it did really well.

MF: We did our first show in November, and…

JB: By then in February we had Scissor Girls and then in probably about March or April, Dogfights from Minneapolis came and played. That was our first out-of-town band, after Fifth Column.

MF: And then we started bringing in bands, we would actually fly in bands…

JB: And then Tribe 8 was touring and that was like our big litmus test, cause they had a contract, and riders and we had to put them up…

MF: Tofutti was on the rider.

JB: Yeah, yeah, vegan meal for 8. but then that one just got insane…

MF: And who was the band that opened, what were their names?

JB: The Pseudonymns, from Minneapolis…

MF: Yes, they were cool, I liked them. They were fun.

JB: Yeah. I could tell you some stories about them. Um.

MF: [laughter]

JB: But I won’t. So Tribe 8 was crazy, and Tribe 8 was really great, because at the time, this was before the whole transitioning thing took hold, the band identified as dykes, but we had a huge gay male presence. But they were, like, the most well behaved men in the world.

MF: They were supportive, basically.

JB: They were supportive, and said, “okay, girls to the front, there’s gonna be a girl pit in the front.” And everybody except for one guy stepped to the back, and had their own pit in the back, girls had a pit in the front, and then after that it just snowballed.

MF: The kinda funny thing was though that this night was doing extremely well. And the owner was of course raking in the cash, but you know, he was still, he hadn’t quite figured out, he was this old Polish guy, he suddenly realized that what was going on here was just a little bit gay, and that there were boys making out and…

JB: Girls making out he didn’t mind, but the boys making out was something else.

MF: And at first he kinda freaked out about it, but then when he realized how much money he was making…

JB: Oh my god, they were making so much money…

MF: Then he was pretty cool with it, which is I guess is the whole story of gay activism.

DT: In a nutshell.

MF: Teah. The revolution shall be marketed.

JB: And then we were in the Pride Parade that first year with Homocore…

MF: Yeah, and our approach to the Pride Parade, I think the first year we actually were good and we actually sent in a registration, but we were kinda treated like crap, um, they didn’t actually, they cashed our check, but they didn’t send us any of the materials they were supposed to send, that they sent to everybody else, and so we were just kind of left to go, okay, fine, you didn’t give us a spot even though you took our money, so we just picked our spot in the parade, and proceeded to make a lot of noise. we had a huge banner.

JB: And it said “Proud of what?”

Our slogans never went over very well. People didn’t get them.

MF: Yeah, what was the other one, “Who’s sorry now?” Somebody yelled, “Leslie Gore!,” and we were like “okay, you are the one person in the entire parade that we love.”

JB: And then we started the newsletters.

MF: Yeah, started the newsletters, which was kind of obnoxious. The idea was kind of like a mini-zine, it would be 2-4 pages, we would try to interview some queer punk figure, so we interviewed like Bob from the Buzzcocks, Thalia Zedek from Come and Live Skull, you know, various kinds of…

JB: And we’d have record reviews and upcoming shows and photographs and stuff.

DT: And this would be mailed to, would it be mailed to people or handed out?

JB: We had a mailing list, oh no, mailed.

MF: We also put them in the cafes and…

JB: Quimby’s, the old Quimby’s.

MF: Quimby’s, Earwax, which at the time, Earwax/Myopic, which at the time were the same thing. Wicker Park didn’t look anything like it looks now, there were like literally 2 or 3 really cool things, and the rest of it was old furniture stores and bizarre storefronts that you weren’t really sure what they were selling.

JB: And I think we learned how, the one thing that really marked us different from everyone else, which was our posters.

MF: Oh, we were obnoxious.

JB: We would make 100 posters, and you put them on every telephone pole in sight, with so much tape you could not get them off…

MF: Not only that, but, everyone else’s posters would have, the band name in big letters. But a lot of the people we were really marketing to didn’t really know the scene, because it was new to them, they didn’t know there was anything queerpunk, so pushing the band names didn’t help, except for a few really big names, but really, we wanted to get across the idea that this was Queer Punk. The band had to be good, but they weren’t as important as that it was Homocore, so we had “HOMO” in letters really tall, and “CORE” was the remaining, was the second third of the poster, and then the last third of the poster was whoever was playing and where it was. And you could see this from about a block away, you could see “HOMO,” in a time when putting “homo” in gigantic letters was, well, we don’t do that now, either, do we?

JB: No, no.

MF: Anyway, yelling “homo” and at the time it wasn’t horribly politically correct. But, it started as Homocore before it was Queercore, and we kinda liked the, the feel of Homocore just sounds better, it’s like hardcore…

DT: So you mentioned that you were in cahoots a little bit with this emerging anarchist community at the A-Zone infoshop…

MF: We went to like their very first meeting…

JB: Yeah. And we helped organize the storefront.

MF: And then it kinda got a little crazy and we pulled away, at least I pulled away.

JB: Yeah, they got a little insular…

MF: Insular and also some of the stuff they were doing was kind of, odd and naïve, and some of the kids were doing things that were just plain stupid and violent without really having a purpose, which was…

JB: There’s a difference between civil disobedience and just breaking store windows.

MF: Yeah, for no apparent reason, just cause of the way they’re decorated makes you think of gentrification. Okay, good, but…

JB: I think James, a former A-Zone member says something really interesting about a few years, quite a few years later than that, he goes, “yeah, we were with the A-zone, and we thought we were doing all this work to prevent the gentrification of Wicker Park, but during that entire time, we didn’t help one family find housing…”

MF: Yup.

JB: he’s like, “nothing concrete came out of it except for a bunch of books and a place for people to hang out and get stoned.” He said “we did not accomplish one concrete idea.”

MF: But they learned. We were all pretty young then, and you know, we all kind of evolve our viewpoints. And they certainly did, cause James Sutter got involved then with the Stone Soup collective.

DT: So punk has certainly been characterized by its association with politics, and its political subject matter. Can you all talk a little bit about any of the connection between Homocore Chicago, to either local or national political issues at the time?

JB: No, I think we just saw ourselves as a progressive bar night…

MF: We did some fundraisers…

JB: Yeah, we did some fundraisers, but they were more for social services groups, more direct action groups and a lot of youth advocacy…

MF: We did one for I think one of the needle exchanges at one point which, you know, ties in with the AIDS crisis, so that’s another aspect where people don’t want to deal with the fags but they really don’t want to deal with the IV drug users.

JB: I don’t think we ever got involved in any kind of local politics

MF: The big, yeah, it was more the larger sexual liberation politics, really. That’s important, you know. For one thing, if you look at the history of the punk movement and feminism, punk, unlike rock music before it, didn’t require that women be sexualized in a kind of, I don’t know, how do you put it, cause they were certainly sexualized, but they weren’t sexualized in an exploitative way, I guess.

JB: Right, yeah…

JB: And really, we had very few tourists.

MF: Yeah, that’s true, only when we had really big bands, like when we had Bikini Kill it was tourist city, but…

JB: Yeah…

DT: Can you talk about what the community that formed around Homocore Chicago was like?

JB: Yeah, it was the A-Zone kids and the No Wave movement, or part of it, Elliot was a part of it, Azita Youssefi, was a perennial attendee, Azita came to every show.

MF: Yeah, but I think a lot of other people went that we didn’t even notice or know, I mean, the guy that’s now my partner of fifteen years… He had gone to a bunch of our shows. He wasn’t particularly into punk, but he was always into alternative music and techno, but even before we met he had been coming to Homocore shows, and I keep on running into all these gay guys and dykes who had been going to our shows, but they weren’t so much identified as punk, they weren’t so much whatever, but they were definitely disaffected with the mainstream scene. And you know, we were something that was different and fun, and…

JB: Well I think how it got summed up was, you go to the bars and you hate the music, but you go to the punk shows and you’re afraid you’ll get your ass kicked. And so we gave people a place where, okay, here’s a punk band, and you can make out with the person of the same sex. And no one is gonna fuck with you.

MF: And it was just an alternative from the gay scene, which you know, by and large wasn’t very political, wasn’t very progressive cause really we were hitting that phase, where … I mean the reason why Queer Nation, for example, arose, was not because everyone decided to be radical, but because assimilation, and assimilationist politics was really creeping into the gay scene. You know, the 70s kind of liberation thing where everyone was being really flamboyant was slowly being dying down in the conservatism of the 80s. Plus the double whammy of the AIDS crisis caused a lot of people to kind of pull back, and try to just try to be normal and try to seek acceptance more than they even had before. And so, things like Queer Nation, things like Homocore Chicago, were just a reaction to all of us that didn’t want to be normal or assimilated, that didn’t want to have kids and a family and serve in the military and do all that other things that you’re supposed to do but weren’t really resonating with us.

JB: Well, even when I went to the first big march on Washington, Pride ’94, and the big issue was “let’s get gays in the military.” When at that time it was illegal to be gay in something like 16 states.

MF: Right, I mean for me I roll my eyes at that whole thing cause we’re people were talking about gays in the military, and gay marriage back then and I’m like, lets just make gay sex legal first.

DT: You have referenced this desire to mix genders, but was there much consciousness or talk around transgender or gender variant people?

JB: Not that early…

MF: I mean, the transgender thing is still fairly new, it existed and certainly one of the folks we knew, Ella, who actually played in some of our shows, her band, she was, when did she start transitioning?

JB: Early…

MF: Early, okay. But she ended up being you know, she was one of the lead singers in one of the bands that used to play shows for Homocore, I think her band headlined the Girlcott that we did. One year we boycotted, or Girlcotted, the Gay Pride Parade over the fact that there was all this sexist shit when the lesbians would walk down there’d be gay boys yelling bullshit at them, and we didn’t think that was cool, and so to kind of draw attention to it, we decided to call a Girlcott, so we had a little punk show up at Foster Beach, and the headliner was actually a transwoman. What was her band called? Ella Santage?

JB: I don’t remember.

MF: 12 inch Tortillas was opening, they were a bunch of high school kids…

JB: And Scott Free played…

MF: And this was funny, because it ended up making the front page of one of the papers, who were saying, the organizers of the parade, “why didn’t they come to us to talk about this?” It’s like, why would we do that? We’re trying to draw attention to a larger problem of sexism, and you guys as organizers aren’t going to fix that. But thank you for making us the front page article!

DT: Related to that, can you talk about the connection between Homocore Chicago and the emergence of these more women-centered types of scenes like Riot Grrrl and the Ladyfest movement and kind of the evolution of that? I guess I’m looking to understand more about kind of the connection between a sort of specifically queer punk scene and sort of specifically female developments…

MF: I was always the de facto Riot Boy with the Riot Grrrls cause I was very close to the scene.

You know, I was just hanging out with G.B. Jones, one of the things that she said, when we interviewed her on the radio show, I kinda said, “hey, what kind of bands should you look at? What kind of shows would be good to go to if you’re a fag or a dyke and you wanna be in safe space?” and she suggested, “well, go to girl punk bands, go to see the Lunachicks, go see…

JB: L7

MF: L7, who else was big back in the late 80s…she did not say Hole.

JB: No, she did not say Hole…

MF: I really agreed with her, being brought up a feminist, I was all into the idea of really pushing girl punk, and so for me, personally, it just made perfect sense. Just as feminism and queer politics to me fit together, cause they’re both kind of looking at a lot of the same gender norms that are expected, there’s a very complementary critique inside feminism and gay politics. And so for me it just made sense that, yeah, of course we’re going to be pushing feminism as part of Homocore, and this other movement that was happening almost simultaneously, the riot grrrl movement just came shortly after queer punk, really, and became bigger much quicker, these two things just fit together very nicely. The fact that we did our first kind of planning meeting at a Bikini Kill show, that says a lot.

JB: Well, we were booking so many of the riot grrrl bands because they knew it was a safe place to play! They weren’t going to get harassed, they knew they weren’t gonna get grabbed, they weren’t gonna get harassed in any way. We had Elliot working sound, who if a girl broke a guitar string and didn’t know how to change it he would do it for her, and not give her shit about not knowing how to do it. They knew that we provided safety, it was, it would either be, from the worst of the riot grrrl groups to the best, they knew it was a place where people would be open to whatever they were doing.

MF: And the riot grrrl movement was always very supportive of gay politics…

JB: Right…

MF: And the Homocore movement and the queercore movement was always very supportive of riot grrrl and feminism. The two went together, I mean, we’ve got a song called Rebel Girl, and Kathleen Hanna, who isn’t really a dyke, talks about how cool this dyke is.

DT: You just said that that riot grrrl got bigger much faster. Since you were kind of inside the Homocore thing do you have a sense or analysis about why that happened?

JB: It appealed to straight girls, we weren’t appealing to like, I mean, Riot Grrrl was inclusive across all orientations, but we were Homocore, you know?

MF: It’s still a bigger stigma being, no one stigmatizes being a woman, they just don’t wanna treat you with respect or give you any, you know what I mean? It’s a different kind of oppression. Plus you had the fact that ties in with the fact that Kathleen Hanna had dated Kurt Cobain, you have this whole situational kind of, you know, the Grunge thing was huge, so anything that tied off of grunge was easy to talk about back then. Newsweek started writing about Riot Grrrl, would Newsweek write anything about queer punk? I don’t think so. The fact that National Public Radio did a little story on us was shocking all by itself. But Newsweek? You wouldn’t touch this kind of weird far-left stream of gay culture, if you were Newsweek. But Newsweek did a story on Riot Grrrl! And so of course it was going to get bigger press.

JB: And I think Riot Grrrl was easier to sensationalize…

MF: It was, that’s what I was going to say, that a lot of guys were frankly looking at it, not as, they were kind of looking at it, as oh, that’s really hot there’s this rocker chick and she’s being all badass. You know.

JB: Right. Maybe she’ll take her shirt off.

MF: Well yeah, there’d be a thing like, we would have guys that’d show up, and Tribe 8 was very much more on the, the queercore side, but we had guys show up because they heard that Tribe 8 would perform with their shirts off. And, it’s like, how do you deal with that…

DT: Building on that, what’s your take on what kind of Homocore activities evolved into and inspired, you know? I’m thinking about stuff like, West Coast things like this Homo-a-go-go festival, or even here in Chicago things like Chances Dances, , there’s been a couple of waves of attempts to basically have radical queer subcultural party spaces in Chicago since the Homocore phase. Can you sort of talk about some of these different eras of it, and how they might be connected or different?

JB: Homo-a-go-go started out as Homocore Minneapolis…

MF: Yeah. What were some of the other ones? There were the various SPEWs that actually happened after the first SPEW. And then of course later eventually you get something like Flesh Hungry Dog, which is up at Jackhammer, but you know, I know the promoter and he is less into punk than just into a queer rock night, so they’re not quite as tied in with left-wing politics the way we were. But, he certainly was into the idea of creating an alternative Queer Night. What were some of the other ones, I’m trying to remember what they all are.

JB: There’s a new one, a queer DJ night opening up at the Whistler…all I can say is that we laid the groundwork.

MF: We did. I dunno…

JB: Or that we built on other people’s framework for…

MF: I mean certainly SPEW gave us the lift that we needed to do for about a decade, just shy of a decade. And I don’t know if we inspired these other people…the other dimension that I think really was more directly inspired by us was Homo Latte, which Scott Free does, which is more of a singer-songwriter type thing, but it’s still kind of politically very similar, even though the genre of music is extremely different.

JB: Right.

DT: Where was that happening?

MF: Isn’t it at Big Chicks now? He’s moved it from café to café, last time I was there it was at one of the places up in, up by Loyola…

DT: And when did you do the last Homocore Chicago show?

JB: It was Chicago debut of Le Tigre.

MF: Yeah, at the Preston Bradley Theatre on…Lawrence? Bride of No-no was opening, yeah, we had, it had been almost a year since we had done a show, right?

JB: Close.

MF: We used to do shows every month. And after a certain point, frankly, a lot of the bands that we had pushed early on became a lot bigger. We did early Sleater-Kinney shows…

JB: Right…

MF: All these, a lot of fairly big-name bands really had their first outings at our shows, but frankly all those bands became bigger and you could go see them at Metro and the crowd that was there, it was pretty much a queer-friendly crowd. I mean, today, if you go to a Gossip show, it’s like a gigantic 2,000 person Homocore, mostly, women, but hey, nothing wrong with that. But you know, lots of fags hanging out too. And lots of supportive straight people. And it’s the same energy just turned way up. And as this trajectory kind of went, became less important for us to do our little shows because frankly, things had changed.

JB: Right, well, when we first started there were no gay people on TV… maybe one or two. But, you know, this was before Ellen DeGeneres ever came out, I mean, it just wasn’t that…

MF: Yeah, there certainly weren’t any normal, there wasn’t any sort of regular gay characters, it was sort of the one guy on a soap, and then, what, I’m trying to remember any gay characters in the 80s…

JB: I know there was a guy on Dynasty who was gay… but, it had changed so much, just in the ten years we were doing shows…

MF: And queer activism changed too, I mean, ACT UP, folded, fell apart to pieces, before they even found all the magic cocktail drugs that, you know, magically supposedly cured everything, though I’m pretty sure that’s not really the case. But you know, a lot of Queer Nation kinda fell apart, a lot of these things started to fall apart way in advance of when their time was, too.

JB: So the last show we did was the Le Tigre.

DT: What year was that?

JB: 2001? Sadie had given me the demo, and I was like, crap, this is good! So fuck it, let’s bring them in, make it one huge thing, and then that’s our goodbye show.

MF: And we literally brought them in, too, because you know, we flew in Johanna and Kathleen took the train cause she didn’t want to fly…

JB: And they had a slide projector, they didn’t even have, they didn’t have video or anything, all they had was a slide projector.

MF: Yeah, they hadn’t worked out the full multimedia thing that they now perform with, but the slide projector was showing Sadie’s drawings, which are awesome, she’s…

JB: I think we just thought we’d do one huge last show and kiss it goodbye.

MF: Yeah, and that was really the last real show we did.

JB: So we went from 50 people at our first show to 600 at our last show.

MF: Pretty cool. And now of course Le Tigre, when they played again, now they’ve broken up, but their shows were selling out Metro…

JB: Hell, they were playing the Vic.

MF: And Sleater-Kinney was selling out Metro and playing Lollapalooza. So you know, it was all these things, got bigger than…

JB: Us…

MF: Us, or what we could provide, or what we wanted to do.

JB: And it wasn’t as necessary for a gay band or a queer band to have a safe place to play, because it was getting safer and safer all the way around. There was less sensationalism about a queer band.

MF: Yeah, well, plus you went on to do your work with Ladyfest.

JB: Right, it was right after that…

MF: So you know, and I started playing in my own band and producing records. I played in this band Heterocide, and I was playing in the Rotten Fruits and enjoying the fact that its actually kind of fun to be out in the spotlight rather than being the promoter. When you a promoter, if you’re a good promoter, nobody knows, nobody knows that you did a good job, they see you, they’re like, “wow, that band was great.” But if anything goes wrong, you know where the blame goes. And sometimes when things go right, you still get blame for things that actually didn’t even ever happen. We’ve had bands that have said “oh, you stiffed us” and I’m like, no, actually, I took a couple hundred bucks out of my own pocket cause I knew you needed gas money. But, fine, go ahead and trash talk me to everyone else, just cause you imagined that Chicago was so big that it would be your major meal ticket.

DT: So you went on to do more band stuff, or are you still playing music?

MF: Yeah, I still play music, Rotten Fruits are on hiatus but we’re getting back together, and I’ve been producing bands, I have, like, a home studio, and I’ve been producing bands like Nikki, VD, Functional Blackouts, Daily Void, just stuff that’s on labels like Criminal IQ.

DT: What do you all feel like are some of the lasting personal or community transformations that occurred through your work with Homocore Chicago? You know, sort of looking back at it.

JB: Well I think it just confirms my belief in the DIY ethic, like I said several times in this interview, I really wanted to go to a queer punk night, so I made it happen. And I don’t know, maybe we gave some bands their breaks?

MF: They don’t know if we did or not, but I think it was important for the queer people that went to the shows to actually have a place where they could be themselves and really start to explore and hook up with other people. Really the more you connect people, especially people that are artistic or creative or somehow otherwise marginalized, the more you can bring them together to really bounce ideas off of each other and really create kind of a creative energy, and a creative community, I think, the more things happen. And I think a lot of people met at our shows and formed ideas or relationships to things that kind of carried on into the future.

I think also it was actually fairly transformative for the punk scene, I mean one thing about Chicago’s punk scene, everyone’s like “oh my god, you are so fucking blatant, at any fucking punk show you go to, no matter how homophobic the band is,” and I’m like, “yup!” and I know full well that there are least a dozen people in the room that know who I am, and that if anyone actually started any shit with me, they would have my back, and that’s kind of a cool thing. And I’d like to think that, you know, that kind of changed the attitude in the punk scene that people aren’t, at least in Chicago’s punk scene, you know the punk scene itself was changed by Homocore, in that it really brought the fact that there’s always been queers in punk, and the earliest punk venues were gay bars, make no mistake about that. But we kind of took that and made it really obvious and really blatant, and really publicized it and made it much bigger, so that, you know, at the end of the day you couldn’t say that you were punk and homophobic at the same time. At least not easily, I mean, obviously punk is far too diverse to categorize, I’m sure there’s Christian punk and I know there’s Hare Krishna punk and know there’s homophobic neo-nazi punk. But by and large, the mainstream punk community, we helped make it very clear that homophobia is just not cool. It’s not acceptable and that really has made it a lot easier for you know, queer bands to be accepted in the mainstream, and for queer people to be more open about who they are at everyday ordinary punk shows.

I mean, at a certain point I didn’t really worry about, I didn’t feel like “oh gosh I need to go to a queer punk night” I was perfectly fine going to a punk night and being as fucking gay as I wanted to, making out with my boyfriend, and that, to me, is the ideal. I don’t really want to live in a fucking ghetto. If I live in a ghetto it’s going to be a punk ghetto, not a gay ghetto, thank you very much.

One thought on “Joanna Brown and Mark Freitas”