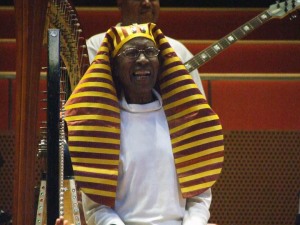

Born in 1927 in Oxford, Mississippi, Philip Cohran played with Sun Ra’s Arkestra and co-founded the AACM (Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians) before establishing the Affro-Arts Theater in 1967. The honorific title Kelan was bestowed on him by Chinese Muslims on a tour of China in 1991. We began by talking about the history of the Affro-Arts Theater at 39th St. and Drexel Boulevard in Chicago, and the performances at the 63rd Street Beach, on Lake Shore Drive, that preceded it in the summer of 1967. During the conversation, we also looked at photographs and slides that document those experiences.

Rebecca Zorach: Were any of the performances at the Affro-Arts Theater filmed?

Kelan Phil Cohran: We didn’t have any film. I wanted to hire a guy to do filming then because filming was just becoming available in the black community’s price range. And so I had a guy put a grant out. In fact there weren’t many grants at that time. But I put a grant out to have him film the shows. I was in touch with Hollywood, and I have a letter from David Foster, who was more or less in the driver’s seat in Hollywood. We had a meeting with him at that time where we considered expanding our programming to include the Hollywood scene.

RZ: You were going to make a Hollywood film?

KPC: Well, we had weekly programs, every week we had a program on Black culture. And the movie houses in the Black community were shuttered because there wasn’t anything people were interested in. And they were trying to spike the interest by bringing in black culture. That was his approach. But they fired him and brought in the blaxploitation films. You know what that is?

RZ: Superfly, and—

KPC: That was the first one. Using my drummer, Master Henry Gibson.

RZ: People were probably happy to have work.

KPC: Poor people are always glad to have work. I never had that philosophy; I do not have money as a requirement for success. My success comes from doing the right thing.

RZ: How did the theater come about?

KPC: Oscar Brown, Jr. was the primary motivator because Oscar came to Chicago in 1966 with a show called Joy ’66 and it was so popular—he had Jean Pace with him and a dancer named Coco out of New York and a Brazilian by the name Sivuca and they had a real neat package. The show was so popular that you had to buy the tickets for next year. I’ve never seen a show like that. Anyway Oscar was so successful that he decided to form a theatrical company while he was here, and he held auditions. I took my band down to the audition. And we impressed him but he said he couldn’t use a band that size.

RZ: How big was your band?

KPC: Twelve pieces. So he said, “I see that your music is different from anything I’ve heard so that indicates you’re a composer. Do you think that you could write music to poetry?” I said of course. So he gave me some money and told me to stop by a bookstore on 61st St. and pick up a copy of Paul Laurence Dunbar’s complete poems. So I got the poems and he said give me some samples. And as I read his poetry—I knew of Dunbar before, but as I read his poetry, I guess with a more enhanced consciousness, I saw that he was truly gifted, in every aspect of Black community life. His observations are impeccable—on the aesthetic of the Africans. So I wrote a couple of songs, took them back to him, and then we began to collaborate on this show. So he said that all of the people who were decent performers should come by my house to see what parts I could give them in the Dunbar show. So I got to see all the top performers in the city, in the Black community at that time. They all came through my house and tried out for different roles. In the meantime, Oscar had a show called Summer in the City. He rented the Harper Theater over in Hyde Park and it was set up with a bank of lights and everything. I think they ran Tuesday through Sunday and he let me have Monday night. And so I took my show in there and that was really the first heritage show, I believe, in the country. All of my material and all of my songs are about the Black experience and Black culture. So the show was a big hit because of the University of Chicago. There were some African students and students from other countries but there were quite a few Black people who came for the show every Monday. And it was a big success. The house was packed. And even Jean and Oscar’s cast came on Monday nights because they didn’t have to work. Oscar never did come, but they raved about the show because it was a new concept. And it was based on the ancient practice of teaching people through the arts. I don’t know of anyone doing that other than Chavez down there with the fruit pickers. Certainly nobody else that I had come in contact with at that time. So that’s how this thing seeded. Because the show—well, first of all, we had put the show on. So Oscar had the idea after taking a bath with Summer in the City—because it had flopped, he dropped about 40 grand on that—and so he searched around for some ways to pick it up on the other side of the ledger. And he had heard about the ESEA [Elementary and Secondary Education Act] program in the public schools. So we went to the Division of Music leader. His name was Emil Serposs and he was from Baltimore. He was quite enlightened; he had had a lot of cultural programs in Baltimore. So he was quite impressed with our show and he said that he could fund it. So they set up a $50,000 package. He said there was only one condition. He said Dunbar had been taken out of the Black public schools because the teachers felt that it would induce the students to speak the dialect —that it would be an impediment to their trying to teach correct English. So I told him that I was a researcher, and that I had done a thorough job on Dunbar and the dialect itself, and that all he had to do was send any detractors to me and I would handle them. He said “Well, if you can do that, you’ve got a show.” So this was in the fall of ’66. And they set it up for us to start in January of ’67. But before they would let us start, they brought in a white group under Russo, who was Stan Kenton’s arranger. And he had maybe a 15 piece group, something like that. And they did two weeks of shows and then they let us go. So we wouldn’t be the first. Anyway, our show was a rousing success. It was so good that after we completed our round and did part of the schools, they placed us in the Museum of Science and Industry, at their theater, and so it was much more comfortable, we didn’t have to move around, we had a stage that was completely blacked out so our colors took great effect, and so there, while we performed, they brought in two or three schools a day, and a lot of suburban schools came in and saw our show. We didn’t know about that till later. But everybody was coming in. Then Oscar knew a lot of people in Hollywood. So all of the different friends came, and I remember Jill St. John was one. But there were a lot of others. And some Broadway people also. They all came in and saw the show and said it was perfect. It was called Lyrics of Sunshine and Shadows. And I had a five-piece segment out of my band, the Artistic Heritage Ensemble. We had Spencer Jackson and his wife, Ella Pearl Jackson and we had Donald Griffith and Patricia Ann Smith. Patricia was a fifteen-year-old student at Marshall High School and she was dynamic. She had a singing voice and she could dance, she could do everything quite well. And Donald Griffith was the dance guy. And he could sing. A little. But the Reverend Jackson and Sister Ella Pearl Jackson—they were power. Anyway the show was quite a big success, and it brought on a lot of other response. And one lady by the name of Betty Montgomery and her sister Bebe Conda came to see our show when it was produced at Doolittle Elementary and she said she had secured a grant of a nice size package of money and she didn’t know exactly how to do it but she wanted to put on an artistic panorama on the lakefront. And they had the beach house which wasn’t being used at 63rd St.—because primarily it was in the Black community and so no one was interested in a beach house over there. We went in and cleaned that up and lo and behold started On The Beach. That was the name of it, On The Beach. So, once we started, it was the Artistic Heritage Ensemble, and everywhere we played, people danced. They couldn’t help it. The music isn’t new anymore, so it’s hard to judge the power that it generated, in this age, after listening to so many copies. But anyway, the band was the main component of On the Beach. They had sculptors, poets, writers, painters—I don’t remember all the disciplines but they set up stalls for each discipline.

RZ: Did you organize that, or did someone else organize that?

KPC: No, Betty came to me for my input, and I set up a band performance, history class, and music training class. And that was the most successful part of On The Beach. The other people had these stalls whereas I had the stage. But the key to the whole thing was that it was on the Outer Drive and a lot of people driving home from work or whatever heard this music coming over into the Drive and after they got home they would straighten up and come over and check it out. But most people who came over to the park, when the music was over, they would go home. They didn’t participate in the workshops too much because it was something new to them. This was more or less the masses who had been trained in Chicago Public Schools. So they weren’t interested in writing, or painting, or sculpture or things like that.

RZ: But you were educating people?

KPC: Yes. Well our sessions and music were primarily about Black history because most of my performances, my compositions were pertaining to something that I had discovered in my research, over the past ten years, into Black culture. An example: Zarlino, the chapel master of St. Mark’s Cathedral for twenty-five years, was a Moor, what they called Moriscos at that time. When Europeans finally subdued Toledo, Spain, they gave the Moors the option of becoming Christians, or die. And the ones who became Christian are called Moriscos. The others went to Sicily and Sardinia and all those islands to get away from the Catholics.

I would bring out things like that and then people didn’t know any of that because nobody had taught them about their history, about the Moors’ part in the history of technology. And people liked it. They saw us dressed different and they liked the music and on the last piece we’d do a finale then everybody danced, so that was real popular, and they would dance all over the yards. On the Beach was fabulous.

[Looking at a slide] This is my wife, Sister Dolores Cohran, who was very instrumental in providing help to me, and changing our dress, and she taught the women’s class at the theater, she had about forty-some members, and that was the beginning of the health movement in the inner city. Because if there was anyone else doing it, they didn’t have the outreach that we had. So we had a weekend crowd coming in to the theater, and we were teaching them about herbs, and how to prepare their food, and read labels, and things like that, we were into Jethro Kloss’s Back To Eden. This is in 67. I just want you to understand that she was instrumental in changing our dress, because she was an expert designer and seamstress. [Looking at another slide] This is Darlene Blackburn, who was also very instrumental in our success. She was a great dancer, and she was beautiful, and everybody loved her, and she had a troupe called The Lively Ones, and I presented her at all of my functions. And Bebe Conda was the wife of a brother that I knew in the Nation of Islam, Simon Conda. They brought him on to do construction at On The Beach. Betty had got the money through some Catholic vehicle. She didn’t know what to do with it so we had meetings and she had other artists. The stage was built by Konda, and we painted it—we did all that ourselves. And after the first crowds came in to see the show, the crowds grew, and grew.

RZ: There were white folks, too, in the audience?

KPC: When we started out, it was like that. But as we dealt more with the content of the program, they vanished. But the crowds got larger and larger. We didn’t know there was an embargo on large crowds in Chicago — of Black people.

RZ: But you soon found out.

KPC: Yes. I mean, the word spread like wildfire that there was a program about Black people. So we enjoyed great success every program. And the crowds got so large we had to move downstairs. We had prominent people, proponents of the Black movement. Lena Mills Golightly, they were wealthy people who came in and sat in on every show. They were devotees. Elijah Muhammad’s grandson Hasan Sharif. Then we started to go outside, and people were sitting all over the walls, all over the ground and everything. At the end of the program we had a DuSable memorial program and we put tickets inside of each balloon and offered a prize to people who turned in a balloon from the furthest distance. We got balloons from Michigan and Wisconsin.

[Looking at another slide] This is the Jackson family. They brought their children in to perform. Spencer, Jr., and Elaine and Cary Jackson—they had a routine of movements with the gospel songs that they sang. And this is how the Staples family got into doing their Black thing on the gospel tip. The Jackson family was very successful, they were very prominent, in fact when Michael Jackson’s family came out performing and people said the Jackson Family everyone thought it was talking about them. Because they were widely known in Chicago.

One day we had a giant rainbow come out of the sky while we were performing. It was absolutely beautiful. Well, we were being blessed from the cosmos.

We had the first health food display for the public, in 1967. My wife had a team of sisters in her class and so we announced over the PA system that they should stop by to check some of the health foods out, that the health food tasted good as soul food. It was our push to enlighten people to a better diet. It was vegetarian, all the way. We were showing them how to prepare pies, and things like that, with honey, and we had a dish that I created called the Cohran, which was vegetables, and very tasty, people ate that. I don’t remember all the menu but they devised a lot of stuff. They became very creative in the kitchen, let’s put it like that.

RZ: What led you to vegetarianism?

KPC: Well, actually, when I first discovered what I was looking for in 61, in the music—I had done musicology studies for about 8 years—and studied cultures—I went home to tell my mother, who was in St Louis (I was here in Chicago)—I went home to tell her that I had found my spot in life. And I had a small hand-held harp, and I played it for her, to let her know I had discovered another system of music, which is the modal concept, and—she cried. And I actually thought she was impressed but she thought I’d lost my mind. Anyway, she worked as a silk presser, and she worked on refined garments, out in the suburbs, you know, and a doctor left his office in the building where she worked, and set a bunch of books he didn’t want anymore by the door, and she saw this book Sex and Psychology, and she said, well, my son’d like this. And she got this book and handed it to me and it was all about vegetarianism. There was a chapter in there on eating meat that if you read it you’d never touch another animal. And this was 1961. So, once I read that, I had already changed all of my other habits, I had stopped getting high, stopped drinking, all of that, smoking cigarettes, all of that. I started bathing in cold water, I let my hair grow out, so I was like, completely gone! (Laughs) So, the diet, I didn’t know much about it but I didn’t want any more chicken. So, little by little, I began to incorporate this thing of just vegetables. I didn’t know how to cook, so I had to devise methods of cooking. I did research on cooking methods around the world, and I came up with a method to prepare meals—that even Hypnotic [Hypnotic Brass Ensemble, Cohran’s sons’ band] grew up on. That’s why none of them are fat. They ate that all their lives. And so it was that food package that made us—all of us rallied around food and the hair and the clothes. That was really the bedrock of the Black movement from our perspective, from an artistic bent. The rest of them took quite some time to get into that.

RZ: How would you compare what you were doing with health and education to what the Black Panthers were doing?

KPC: They didn’t know anything. They had a breakfast program and they served sausage and eggs! I was already a vegetarian for about five years then. The sisters would serve out food to the crowd, who just wanted to listen to the music, but we were trying to move them to another position. And eventually, they did — because everybody started wearing their natural hair. That’s where the natural really caught on, right there in those performances. Because all the members of the band had a natural, I had been wearing a natural since 61. And I explained that it was an attempt to discover who I really am, my natural self. And so a lot of people got into that. Now we got locks down to the floor! That was long before the movie Hair, which made a big impression on the white community. (We didn’t even know that white men had long hair, and it was a shock to us to discover that their hair was down to there—see, our hair only grows so far.) And it was just the general concept. The alderman, Despres, came to find out what’s going on in his ward, with all these people, out there. The Blackstone Rangers performed on the stage. That was well attended.

RZ: What did the Blackstone Rangers do?

KPC: Well, they had a show, called Opportunity Please Knock, and Oscar had helped them put it together. In fact it was under his direction. They went all the way to the White House. They performed in several cities and then eventually they were greeted at the White House by President Nixon, I believe, and given a million dollar grant or something like that. And so the gangbangers were highly accepted because they were trying to change the conditions in the neighborhood. And of course they used some drastic measures but that was their motive, was to change their condition from welfare communities to fare-well. Anyway, we had broad support.

There was a drum class. Master Henry was the main teacher there. There were a lot of people learning to play the drums. Because the hand drum was not yet in the black community. There were a few fellows playing it, and no whites were playing hand drum at all.

RZ: And where was that class?

KPC: That was under the structure there, of that beach house. There were several rooms, I had a classroom for my history class. So I taught Black history at the same time. This had a great deal to do with the momentum created in the Black community.

RZ: In your interview with Clovis Semmes you said that was when Chicago became Black…

KPC: Yeah. That’s what it was. Because most of the people didn’t know and there was no vehicle to deliver that information to them with the exception of Muhammad Speaks. And that was a religious approach. A lot of people, they’d look at the paper, and they’d listen to Malcolm speak, but they were not necessarily impressed with the religion. So it wasn’t until we got out and put music out there, and the music converted a lot of people, just as it’s doing today. What is the music about? Shooting, bitches, a whole lot of other stuff like that, and that’s where it comes from. Because we are almost automatically changed by our music, as a form of instruction. So when the music’s positive—people become positive.

We also had readings from scripture, and prophecies—we had a Hebrew brother reading a text, of the prophecies. That was a part of our program. Chief Fast Wolf participated in some of our ceremonies we had about DuSable. [Looking at a slide] This was a chief, I guess you’d say ambassador, of the Hebrew Nation in Israel. There’s some 5000 people living there now who came out of Chicago. So that’s the ambassador. He was my student, on alto saxophone. And there’s Darlene Blackburn, outfitted in the back there. This is the audience while the performances are going on. And the guy in the black was Characka He was one of the Main 21 of the Blackstone Rangers, and he would come to our theater and appeared in some of our presentations. (They said his girlfriend walked up behind him and shot him in the head.) There was about 2,000, 3,000 people there. I took shots when I was on my way from the dressing room and things like that.

[Looking at another slide] We had a flute jamboree, because a lot of guys were playing flute then, so we had all of them just come up and do a presentation. The gate there, to the boat yard, is full of people listening – this is the last day. There’s Haki Madhubuti, Don Lee.

At the last performance, we asked the people, would they like to do this year-round? Because it was the last day, Labor Day, the last day of programming. They said Yes! So I told them all, to come to the St John Grand Lodge on Ingleside tomorrow night, and I’ll show you how to get a theater. So, about 80 some people showed up, and I gave them sheets, little pieces of paper with my signature on it, authorizing them to solicit funds for a Black cultural center. And they took them to beauty parlors, and barber shops, and filling stations and automobile repair, all kinds of places, and they collected quite a bit of money.

And I went downtown on LaSalle Street, or whatever the street where the money people are. And this guy, Gene Gelbspan, who owned the building, and had his office in room 666. Awful symbolism. But anyway, he was a nice guy. And we sat down and worked out a deal for the theater on 39th and Drexel. 3947 Drexel. And so we worked out a deal for that. And then he took me out to 79th and Ashland, where they had a large theater, that’d hold 3000 people, with 8 dressing rooms on each side of the stage, a huge facility. And it had 5 stores, I think 13 offices, and about 18 apartments in it. He offered me that for $5000, just turn that over to him and I’d take over management of it. But my team had grown so fast, I didn’t want to take a chance on all of the money in one basket like that. You might say I was cautious. So I made an agreement with him, I’d keep the theater on Drexel, 6 months, and if it worked out all right then we would transfer to the larger theater. So it was a good arrangement. So we went in there, and the theater—it was a wreck. We went in and painted the walls black. All around. It cost quite a bit. But the Blackstone Rangers went to all of the hardware stores in the neighborhood and made them donate paint. I went to the gang king meeting in the neighborhood and told them that we were bringing these programs for them and their families and that we’d respect them as caretakers of this territory and all of that sort of thing and offered them anything, and if they wanted anything to see me about it, and they could come in the theater any time for programs. We didn’t charge them. So then we were very well protected by respecting them like that.

[Looking at a slide] I did the first marquee myself. We were going to have a more permanent thing put up for Affro-Arts, but since we were going to move, we just left it up there. The album I have, Armaggeddon, that was recorded there. In the lobby of the theater, we had a rainbow in the ceiling and gold leaf was the theme. A theater owner came and said How did you do this? We put $30,000 for my theater and it didn’t look this good. But we had the community cooperating with us.

When you entered the inner theater there was a board set up so you would know who was on. It listed the Artistic Heritage Ensemble, all the members and what they played, and the cast, Darlene and her Lively Ones, the Spencer Jackson family, that was our fare. We played three nights, Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, the same show, every week we changed shows the next week. So people developed certain nights that they’d attend.

[Looking at slides] This was a song called “Ladies, the wig has got to go.” This is the back of the theater. The theater wouldn’t hold but about 2000 people. So if you came in late you had to see the show from here. We had a womanhood class, which my wife taught, and a concession stand. We had the cosmos on the screen and the band in front. This was our Queen, who was selected on the basis of her attitude, and she sat on the stage for all the performances. Her name was Naema.

RZ: It had been a movie theater?

KPC: Yes. Oakland Square, was the name of it. And the theater ran fine, but the license for it was held back. We had paid the $250 for the license but they didn’t issue it. So up in March, they closed us for operating without a license.

RZ: And was that because of Stokely Carmichael?

KPC: Well, that was because of Stokely, yeah. Mayor Daley had declared Stokely would not speak in Chicago any more. So they shut down all the churches, all the large venues. That’s when we discovered there was an embargo on gathering places for black people. So he came to me, and asked if he could come to the theater. A SNCC representative came to me. Well, they had beaten me out of $300 before, we performed for them and they didn’t pay us, so I told them they could come in if my $300 was taken off the top. So they agreed to that. And I won’t go into some of the other details. The show was a big—well, it was on a Monday night, and when I got to the theater there were people waiting in line, around 5:00. By the time—say 7:00, there was three or four blocks of people waiting to get in. And a battery of newsmen from all over the world. ‘Cause Stokely, I guess, was at his apex at this time. Red hot. And so they came in the theater and I had my engineer there to hook them up, around the stage, a bunch of maybe 30 or 40 of them all wired up around the stage.

And then Stokely comes in about 8:00 and he says, What’s all these reporters doing here? And I said, Every time you do events, there are newsmen there. And he said, Well they didn’t say anything that I was going to be here. So put ’em all out. So I had to go and tell them that they were evicted. And they got up, started pulling out their equipment and stuff, and the audience booed them. And as they moved out they said it was a race thing. But we put some Black people out too. There were Black reporters from ABC, and NBC, and the only person left from the media was Roy Woods, who had announced on WVON that Stokely would be there that night. But the word of mouth was tremendous in the Black community.

Anyway, we went on with the program—I taped all of that, all of those speeches and everything. We went on with the program, and that night, while the newsmen were outside, filming the marquee and talking all kinds of trash on us, the commander of the police second district—his name was Willie Pep—said “You’re gonna have to let these people back in. There’s a law against discrimination in the State of Illinois.” And so I said, “Well, we put out the Blacks too.” And they said “You can’t have events where the press is barred.” And so there was a cordon of brothers behind me saying, “What’s the problem, Brother Phil?” So what they realized, it was a confrontation. I’m more than certain Pep had a cordon of police lined up somewhere, you know, but he came in diplomatically, by himself. So he said, “Well, there’s more than one way to skin a cat,” and he turned around and left. He chose not to fight. But everybody knew that we were ready to boogie.

And the next day, a policeman came and says we have to close down for operating without a license. And I said “I have the receipt here where we paid the license fee in December.” And this is March. And they said “That’s no good, you’re closed.” So, we closed, and went through a lot of changes, communicating with politicians and whatnot, and we hadn’t even approached the politician in that ward and he was upset about that, because he thought he had power, and we didn’t even acknowledge him. We opened the theater without acknowledging him. Anyway, I talked to Pep and he said, well, you can operate but you can’t charge anything. They thought they would break us by us not making any money. They thought we were hustling. See, all of our people were donating their work anyway. So, we opened up, FREE. The weekend. Everybody came in free. We took up a collection, I told them, I said, “Nothing operates in Chicago without some coins.” So we took up a collection and made more than we ever did on the tickets! So we operated that Friday night, and then Saturday morning the guy came in with his pistol. That’s when the policeman came in with his hand on his gun. And he said “You’re going to have to close, now.” So that was the theater closed.

RZ: That was in the spring of ’68?

KPC: Yeah. Spring of ’68. So I went out and put on the marquee “WE ARE CLOSED BY DECEIT.” That got everybody upset because it would precipitate a riot, you know. So the owner of the theater came out and he said, Look, let’s cool down, we’re gonna work this out. ‘Cause his investment was at stake. So I said OK, and they brought in [Ralph] Metcalfe, who was Daley’s right-hand man. Metcalfe says, “Well, we’re going to do this right. We’re going to open the theater back up but it’s going to be done in the proper manner.” So they brought in their engineers, and they said, “This stage has to have a firewall, because it’s endangering the public. So and so and so.” They came in with some more requirements, which all ran up to I don’t know how much, a nice taste of money. And then they fixed that, and still wouldn’t let us open. ‘Cause some more things had to be done. What I realized is they were playing dirty pool with us. They would’ve strung us out all the way up till now, and we never would’ve opened.

So we waited until the fourth of July, when everybody was celebrating Independence Day, and I called a press conference. On the fourth. So all the people come out, what’s this about, what’s this about. I said “You’ll see when you get to the conference.” So when they got to the conference, we were opening on Independence Day, you know, because we’re a free people. And they called the city department and they said “Yes, we permitted them to open.” So we had a bunch of tactical movements. You know, they cut our lights off, and I went and got three lanterns and lit the lanterns up there. So that was the fire insurance. So they went and turned the lights back on. Everything they did, we countered. So they let us open back up, and we brought Stokely back, in, like, August, so everybody’d know that we didn’t sell out and we didn’t compromise. So he was there twice, March, and August.

But I wasn’t a supporter—what is his African name, Kwame Toure, but Stokely, what I knew him as—they were young people and they didn’t have a background in culture at the time. And so they were just being revolutionary. I had been dealing with culture for over ten to twelve years. And I thought the cultural approach would have been very successful if they had left us alone, but the political people jumped on us. And so that’s why the thing was closed for political reasons. And then they opened up other theaters, with the condition that no politics be allowed.

[Looking at a slide] This is Eartha Kitt, with a friend of a lot of years, he was the PR man who put Mayor Hatcher in office in Gary. He was the one that ran the $1000 page, one page ad in the New York Times, that’s the way they raised funds to put him in office. He was a PR man to the core. He told me, Phil, I’m going to put your theater on the map, as soon as I get through wrapping up with Hatcher, I’m coming to the theater, and he was inspired and everything. But they had a PR thing for Eartha Kitt, she was doing a program called Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, after she had embarrassed Lady Bird Johnson at the White House. Because Lady Bird had invited her over, as a Black supporter for their program, and they suggested something, I don’t know what it was, and she objected to the Vietnam War policies. And she became a Black hero at that point. And they invited her to Chicago, it was a big promotional event called Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. And this guy devised the scheme, and he rented hearses, limos from the funeral home, they had about six limos, and they went to all the prominent places about town a couple of nights before. But this was the night before the show, Saturday night, and they stopped by the Affro-Arts Theater, the entourage, and he had pictures there, and they went to taverns with them. Everywhere he went he was drinking. And he got tired and went home and died. From the alcohol, that same night. So that was the last picture of him. I had to tell you that story. We had Fats Crawford, he was the head of the Deacons of Defense. They were the guys, in Mississippi when the demonstrators were getting beat up, the Deacons of Defense got shotguns. So they said aint nobody gonna beat us up. Tell me again what is the subject of this interview?

RZ: Art as a force for political and social transformation.

KPC: Well, that’s what it is. But once the politicians identified that, they took charge of the arts. And the arts went down.

RZ: I’m also interested in the 1960s because I’d like to see if we can learn from the optimism and ideas of the 1960s and maybe avoid some of the pitfalls.

KPC: That’s impossible. All that you can do is record it. There are forces at work that are larger than we are. I know because I experienced it, I was attacked.

RZ: That was by the Chicago police, the FBI?

KPC: It was J. Edgar Hoover, because he brought in the CIA, which was supposed to be for international affairs, and he brought them in to the domestic scene. But that’s a story for another day.

RZ: I have a few more questions. First, was the Affro-Arts Theater something you always knew you wanted to do, or was it an inspiration of the moment?

KPC: I always wanted to have my own place to perform where I could leave my equipment. I’m trying to get a place now. Rather than hauling it back and forth all the time—I’m 84 years old, it gets exhausting! But it was because of Oscar Brown and On the Beach. With the crowds that we had.

RZ: So it was the excitement of the moment?

KPC: It was the advantage of the moment. We saw that it was possible. It was spontaneous.

RZ: My second question is about the Columbia College conference in 1968.

KPC: Some of these people who run the country decided that it was time to investigate what was going on in the arts in the communities, because they really had paid no attention to that before. So they had this conference on “The Arts and the Inner City” and they held it at Northwestern Dental School. They paid the presenters $75 for our participation. We had all been successful with arts in our communities. And then a group of Black artists from the community decided to hold a protest because they had not been invited. Jeff Donaldson, he was a big tall brother full of anger, he was the leader. So they decided to split into two caucuses, a Black caucus and a white caucus. And the Black caucus came out with the statement that the Affro-Arts Theater should be reopened. And the white caucus came out with a very strong statement against racism in the United States. And they came over to the theater and we opened it up and held the conference there and they talked and then we put on a show. We recorded it — I have it on tape.

And then people donated their fees to us, and Alexandroff, who ran Columbia College, donated $800. And then they said they wanted to follow our teachings in their curriculum. That’s why they have the Black Music Center at Columbia College.

This was the beginning of grants. There were white institutions that were interested in offering money for arts in the community. This group COBRA—they had opportunities to ask for money and they didn’t…

RZ: Who was offering them these opportunities?

KPC: Everyone, MacArthur, the Pritzkers, anyone you could think of, they were all there at the conference and they were quiet about it, but they were there. COBRA had the opportunity to ask for money. But they could not decide what they wanted to do.

RZ: And so these white institutions, do you think they were offering money mainly because they were scared of riots?

KPC: Yes, they were scared because this was what was happening. But I think there were some of them that were also enlightened.

RZ: Could you say a little more about how you see the relationship between the arts, culture and education part of the Black movement versus the more political side, like Stokely Carmichael and SNCC and so on. You talked about how you were working along the line of culture and education and the militants came in and sort of created difficulties for you. How did you see the balance between those two sides of the movement?

KPC: First of all what I was dealing with was premature. It was the same as Sun Ra. Visionaries—well, when you can see the future and you govern yourself accordingly, when you see the past and you govern yourself accordingly, you have to step outside of the flow of society, because it’s on a binge, trip, or hangover or something. A cultural hangover, I would say. I don’t condemn or criticize anyone for the way they feel; I think we have the right, having been treated the way we have since being kidnapped from Africa, I think that any condition we wind up in is legitimate. So I don’t criticize anyone. I would like that printed, in those words. From studying musicology, and European culture, and then eventually going in and dealing with astronomy and archaeoastronomy and seeing the true vision of history, which was hidden, then it was like discovering a gold mine in the garbage can, I guess. I didn’t know how to approach it, it’s so much. So what I did was I wrote compositions. Each composition, before I played it, I’d explain it. And that became my modus operandi. And people all benefited from it, especially the masses, but a lot of scholars were disturbed by it because they didn’t learn those facts in their pursuit of a degree. So it was outside the academic world.

And the revolutionary people were all wanting to fight, they wanted to get even, it was a thing like “let’s teach these honkies a lesson” or whatever. That’s the extreme group. And then there were the Muslims, in which I was a lieutenant, in the Nation of Islam, they had a disciplined approach to the liberation of our people. There were the Hebrews, there were a lot of different factions. But the younger people, like SNCC and the Panthers, they’re touted now as heroes—which they were, they were willing to sacrifice their lives, but we were too. We knew that we would be attacked for what we were doing. But I think if we had worked gradually, we would have been allowed to pursue cultural enlightenment, and it would have eliminated the dilemmas we face today. That’s what they’re taking into the schools, now, with my program that I was running in ‘67, ‘68, they’re taking that to the gangbangers and people who’re in jail, now. Well, all I wanted to say is that the revolutionary arm of our movement made it almost impossible for the cultural arm to exist in harmony with them. They’d get on the stage at Affro-Arts Theater, and say “get yourself a gun, do this, do that.” I didn’t have a problem with that, I already had a gun, that wasn’t the problem, the problem was why would you taunt the people that you know are against that, why you trying to show them what you’re doing? I just didn’t agree with that approach. I thought the problem is enlightenment. Our people still suffer from that. Even if we had won some type of physical victory we would still be ignorant. Going in the pyramids, going back into history, hasn’t delivered large enough numbers, hasn’t made enough impact in our community, to stop us from killing one another, to stop us from hating ourselves and from trying to be something that we’re not. So my approach was to focus on what I was responsible for. I changed my diet and taught people how to eat properly. I used herbs at a time when the medical profession was laughing at it. I wore a natural to show that I loved myself in the natural state. And all of these things, I thought that this approach would have brought about an enlightened black community which would be in a better position to bargain or assert themselves politically without being negative. Because we all have a future and we’re all responsible for one another’s future. And I know there are people who will never see, as Abraham Lincoln said, there are white people that will never accept us as equals, and I don’t need that person, I don’t want to be equal with nobody, I’m satisfied with myself. So I think that’s very important. If I could have helped facilitate that attitude in the community. We had programs designed for that. We taught music. Not just to play music, but we taught why they play music, and we taught the ancient system. We taught language classes so they could learn the value systems of the ancient societies. But most of all we had people who’d come from traveling, to give lectures and talks in the theater, and then we had a program each weekend which displayed my facts that I had gleaned from extensive research over about ten or twelve years. So—my whole thing in summing up the Affro-Arts Theater was that it was too early. And I’m sorry. I’ve taken responsibility for that. I should have moved a little differently. If I had taken more time maybe my approach would have had a better day. But we were moving towards a collision—with King, and the movement in the South, and the killing of various people, lynching and all that. So—maybe I should have taken more time to perform and do things rather than open the theater when I did.

It definitely was a shock to a lot of people. Lot of people walked in the lobby and were astounded. They had never thought about owning a theater. Never crossed their minds. And so there were people who left the theater, many, at night, and were inspired to go out and launch some type of activity on their own. And some of it was bad! I had letters from prison, couple, maybe three people wrote me that I was responsible for their going to jail—because they got enthusiastic when they left the program and attacked some people, you know! That was just a few. I’ll say that looking back on the Affro-Arts Theater, to me, it was too early.

If I had been fortunate enough to just keep on playing, because I had an excellent band—Duke Ellington’s bass player wanted to leave Duke and play with me! (I told him it’d be better to continue with Duke Ellington and I never heard from him again.) The band was really great. We had reached a place together that very few artists reach together. It was Duke, in the old days, when I saw him back in the 40s, his band—they had what we had. All the old bands worked for that, and they stayed together 8, 10, 12, 20 years, like that, and there was a unified approach to their statements that can’t be matched today on any level. So, if I had pursued that, just playing with the band, and making performances and things like that, we possibly could have gained national recognition.

But I don’t know. J. Edgar Hoover was on a rampage so his object was to cut down anyone who was dealing with heritage or black concepts. And he made a statement that he wanted to especially contain those who had a messiah complex. That is, people who the masses looked up to. So I was targeted in that sense.

They took the theater down, and soon it went over to the El Rukns. And even then, I didn’t think that that was all that bad, even though they were young people and didn’t have any knowledge. But they did have a sense of wanting to survive. And so I always honored them. On my album, Armageddon, you hear one—in the final piece Armageddon, you’ll hear Reverend Jackson speaking, and Rico Cranshaw, who’s one of the Main 21 of the Rukns, is giving the response. He quite often came in the theater and worked with us. And Sharaca, another leader, also worked with us. And plays drums and stuff. So we weren’t that far apart, except that they came about through violence and I came about through enlightenment. But we were on the same path with the same purpose.

RZ: I’m really curious about that component, and how they came to join with you in that purpose.

KPC: Well, yes. It’s because we went to the gangs first and told them that we were bringing a program in their community on their turf, and we gave them respect and offered them anything they wanted to help us. Because we were dealing with their mothers and their brothers and sisters and fathers so I said, this is a community thing. And that’s the reason Jeff Fort reversed it when Bull brought a group down to take over the theater from me. I told you about that.

RZ: No, I don’t think you did, actually!

KPC: Oh, yeah, Bull charged in the theater one day with about six guys, “No more Phil Cohran Artistic Heritage Ensemble, from now on it’s BLACKSTONE.” And I told them just what I told you, that this is a theater for the community. I went to Four Corners, which is an arm of the gang down there, and what’s his name, Thunder, and I told them all, they’re part of this too, they could come in anytime they wanted to. I had it open. So I said this is already part of the Blackstone thing. You have an organization, I just have a few people—you could get your own theater. He said, “well, you’re gonna regret that.” So they went home and argued over whether to put a hit out on me. ‘Cause when they put a hit out, anybody gets rewarded that kills me. So when I went home, Rico was waiting for me to come and park. And he got out of his car and came over to me and said “They’ve been arguing over whether to kill you or not. And some of ’em admire you because you stood up to Bull. And the rest of ’em want to see you dead.” So I said, “Nothing I can do, I appreciate your warning, but I have no defense against something like that.” So the next day, Jeff Fort came to the theater to see me and he said what is this about. And I explained it to him. And he said, you’re right. And he got up and left. And about thirty, forty minutes Bull and his group came back and said, “We apologize,” and left.

RZ: Who was Bull?

KPC: Bull [Eugene Hairston] was one of the Main 21. He was, ah, the most negative. For me, anyway. Cause I’m a bull too. He come in and said they’re gonna take over the theater. Soon as I left, when I had this big dispute, soon as they heard about it, they came in and took over and the rest of the guys said “Blackstone!” So that was it, it went down—parties, and pot smoking, not really dedicated to any particular cause.

But they had a definite code which was identifiable. It was like Jeff came to the theater and sat in judgment over the dispute we had, rather than put out a hit on me. Because Jeff had come to me and Oscar Brown, Jr., a year earlier, or maybe it was two years earlier, to help them with Opportunity, Please Knock. And so I had always been open to them, we performed for their events, so I didn’t have a problem with him, he didn’t have a problem with me. So he came to look it over, and when he did, he made his decision and I’ve respected him all my days.

I say that they are victims really, politically, just like any other revolutionary group. They were kids in a neighborhood that was being exploited to the fullest degree. Welfare mothers, no fathers. So the boys, they got together and went to the stores all up and down 63rd Street and told them they’re gonna have to pay taxes. And so once they did that they’d bust windows or something if they didn’t, I don’t know about all of it but there’s plenty of books on how they got started and what they did. But they always had a code. They always had leadership and they always stuck together. So they grew to at least 5 and maybe 20,000. I don’t know. But the thing, by me being respected by them, I’ve had brothers tell me that they ran the wineheads off the street, because they didn’t want their children to see the wineheads, as a result of my performances, and listening to my concept. I had a lot of brothers stop smoking, and things like that. They listened to me, I was considered like an elder.

But I never supported any of the things that they had to do. Except I believe they wanted to turn the theater back into a cultural institution. Because as Jeff was in prison he was learning and he was growing. So I got the message that he wanted me to direct a cultural center. And he knew what my turn was. So I respect them as being enlightened. Maybe that’s why they got the 80 years in prison. They treated him like Al Capone or something and that wasn’t the case. There’s lots of gangbangers out there now that they’re responsible for putting on the street rather than taking off the street. But they got Jeff off. And I want to mention also that he stopped crack from coming to Chicago. And they know that. The police know that. And the government knows that. Every time they sent a crack dealer here, they found him dead. They didn’t have any way to get crack into Chicago until they got Jeff Fort out of the way. And crack, the worst destroyer of families and community, has been running rampant ever since. So it’s a matter of six in one hand, half a dozen in the other, as to who is justified in doing what.

Because in the end, the black community has been reduced to shambles. And no one in the black community can walk home tonight without looking over their shoulders and keeping on the alert, ’cause we live in a war zone created by the political situation. And no one mentions it, in fact we are not even considered legitimate victims, and no one in the schools or anywhere being taught what the Middle Passage was, most people don’t know what it involved. They might have heard of it— but they don’t know what it is. And so those are the type of things we were dealing with, let’s bring the abject truth right up front, and let’s deal with it. So I don’t expect you to do that, somewhere along the line I will have the opportunity, and if I don’t, some of my records, some of my lectures, some it’ll get through.

RZ: Obviously you were combining music with a lot of other kinds of learning. But I’m also wondering also about the music as music.

KPC: Music is the language. It’s the cosmic language, it’s the divine language, it’s the language of the original people. I’ve discovered and have been teaching for at least forty years that black people sang before they spoke. The languages came out of songs. And so their environment was sustained by their song. And that is one of the reasons that I’ve said that we were far more advanced two, or three, hundred thousand years ago than we are today. And that evidence is hidden because it was all rainforests and the sub-Saharan environment, and that’s an environment that does not preserve things over any period of time. But there are some brick structures that have survived, and there are some monuments that have survived. And by learning how to read and interpret the symbols of my ancestors, I am in a position to prove that they were enlightened. The scale that we use today came from way back more than 100,000 years ago. And they call it the Greek modes—that’s a joke! Because the Greeks got it from the Ethiopians. It was an ancient science, connecting our bodies, our environment, and the sky. I won’t go any further than that—I give lectures on it—when people are ready to find out the truth, and reality, I’d be glad to give them the proof that I have. It comes from studying ancient astronomy, and there are no advanced civilizations that obtained this height without a thorough knowledge of the cosmos, and that’s what it comes from, from ancient India, China, Peru—the Nazca lines—Cambodia, here in America, right down at Cahokia. Nothing but an observatory. You go up there on the mound and all you see is a bowl turned upside down. So all, enlightenment stems from an understanding of divine order, which is the flow of the cosmos.

RZ: Would you be willing to say a little more about being targeted by J. Edgar Hoover?

KPC: Well, the Stokely Carmichael thing, that’s how that came about. Alex Poinset of Ebony Magazine had processed a grant from First Unitarian Church for the fall of ’68 and J. Edgar Hoover moved in around September. We had a big argument and nobody knew where it came from or what it was about, but it broke up the organization and I left two weeks before the grant would have come through, so it was cancelled. My secretary was working for the feds.

They might have had me targeted all along, but there were lots of other revolutionary artists who didn’t have a problem, you know. I had tried several ways to enlighten people. This is what our problem is, it’s one of ignorance, and the dominant society continually feeds this ignorance. With television, that’s all it’s about, all these media, the public schools are a disgrace. Even today, with all the charter schools, and all that, all they want to teach is math and science, they don’t want to teach culture. They don’t want to teach art, and true inner expression.

We are an ancient people. We are the most ancient people that walk this planet. And in us is the very record of all human existence. That’s suppressed. They’ll use that in rap, which is maybe growing to some extent, but I see it mainly declining, because with the lack of knowledge how can you approach the future? That’s our problem, and it can be solved any day that people are serious about wanting to solve it—just turn the game around, and be real. That’s why I teach. There’s no real problem with the younger people, they just don’t know any more than what you teach them. There are a lot of young people out here now, 10, 12, 15 year olds—brilliant. But what are they being taught? Just one thing. How to serve white people. They’re never taught anything about themselves. They don’t know what the Middle Passage is. No one accepts the fact that we were kidnapped. They raise such a ruckus over all these modern-day calamities and bad deeds, but no one has anything to say about a whole people being kidnapped, just stolen, and put on boats and the majority of them didn’t even make it to this country. They threw ’em in the Atlantic Ocean. Then when they got us over here then they stripped all of our knowledge. Anything that we knew of the past, they forbade, and they punished us for dealing with our names, our language, or our customs. The only thing they let us do was sing. And therefore in the songs are the secret keys to all of the culture that happened before.

That’s why I gave a lecture at the Adler Planetarium, Slavery and Astronomy. ‘Cause that’s all they were talking about—the cosmos. Well, I hope you print this. I don’t have the ability to put it out, now, but I’ve got hundreds of lectures and performances. They all speak of one thing. I never performed for anything else, except at the Ethiopian cafe, I play there for a living, so I just play the music. I don’t sing or recite poetry or anything like that there. But any other engagement I have is to enlighten people, everybody, because no one knows what happened.

This is one of the worst societies in history so far as information is concerned. They hide this, and that, and the only thing that happened is they created the technology that’s going to strangle them. Because the internet’s been hitting them, giving them a black eye, over and over. I don’t know how to use computers and things, I dabble in it. I just have too much of a schedule, I have to practice every day, I have too much activity keeping my house and all that. I don’t have time to be learning something that’s very elaborate like computers. But I just hope you will print the truth, and not allow anyone to delete what you might call sensitive material. I believe that times are changing, and maybe we are in another age where people are seeking the truth.

RZ: That might be true.

KPC: If it isn’t, we’re just in the same shape as before and we’ll make the same mistakes. Somebody said, you cannot use the same techniques when you fail, and expect to get different results. If you use the same thing you’ve been using, you’re gonna end up in the same place. I’m sure you’re aware of the economic disaster that we face, and most people are trying to figure out what they’re going to do. But there’s no way to plan it because we’ve never had this before and no one knows how it’s going to react. So we’re certain to be faced with pandemonium in a few months. I’ve already predicted disaster.

RZ: Have you been following the Occupy Wall Street protests?

KPC: The bankers. Yeah. That’s the force we have to deal with, this one group. They run the world and the world has acquiesced to them, so far, but the masses, who are the victims of that process, are breaking out all over. 72 military installations that America maintains with our tax money and here we are broke, can’t pay this, can’t pay that, and here we are with 72 military installations around the world, indicating that we are running these military bases to protect business interests, not the people of America. Because if they were protecting America they wouldn’t have sent all those manufacturing jobs overseas for cheap labor.

You know the people are going to revolt. Like they did in Egypt and all over the Middle East for the same reason. They’re looking at wealth, and they don’t—it’s not even close enough to smell. So people are—they get angry when they’re not working. I remember in 1958 that’s the first time the American people really got angry in my lifetime. They really got mad. That’s what brought on the Civil Rights thing in the 60s. The early 60s. Cause they didn’t have jobs. As long as they were working, could buy their Cadillacs, and Buicks and all those cars, and do all their simple pleasures, everything was cool. But there’s a doctrine of the satisfaction of the people, about the percentage of satisfaction of the people, I don’t remember who put it out, but the people in control always have to watch the percentages, because when it gets to a certain point all hell breaks loose. So we’ve gone past that point, now, and I would say that the election really isn’t important—we’ve got to get through October. That’s my assessment of it. Becuase being an astronomer, I’ve looked at the cosmic patterns, and they don’t support anything reasonable this year or next year. It’s already starting, it started good, back in the spring. You see Black people are aware, all these things happen in a pattern, and series. They look for another reason. They don’t think that it’s just circumstances.

You see, most of the power structure are these non-spiritual lawyers and people like that, they think of it as just an occurrence. I’m not superstitious, but most of the Black people know something else is happening, and it’s going down in regular fashion, every three or four days, something has happened. Volcanos, fires, mudslides, earthquakes. Never heard of a thing like the rain standing in the same place like it is in New Orleans now. That’s a new one. We get five or six inches, but 20 inches in one place. Who ever heard of a thing like that? In Winnetka, the wealthiest community in this area, had flooded basements last month. Flooded basements! The elevation goes up higher and higher the further north you get. That’s why everybody lives on the North Shore—because they are protected from lake overflow. So they never expected to have flooded anything. But they had so much rain in one time that the water had no place else to go. Some lady was on TV crying “my wedding pictures”—you can’t expect people to have sympathy for that when they’ve been out of work for a year, six months, something like that.

But I never worry about any of that. By me being 84 I’ve done everything I wanted to do, so what the hell. My interest is that the truth would be recorded in as many places as possible. I’ve been blessed in my life. And my music is selling all over the world. And if it didn’t sell, it wouldn’t matter. I’ve always had the tools for survival.

I’m speechless.

Crucial Knowledge and history

The Truth!

Maximum Respect to Brother Kelan Phil Cohran