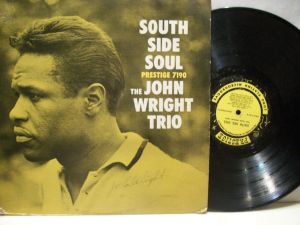

John Wright was born in Louisville, Kentucky in 1934 and moved to Chicago with his family two years later. As a child, he was immersed in the gospel music of his mother’s church; he learned jazz piano while stationed in Germany in the U.S. Army during the Korean War, where he also met Dizzy Gillespie and Dexter Gordon. His first recording in 1960, with the John Wright Trio, was entitled South Side Soul, a phrase that became his nickname. Over a lengthy musical career, and work as a librarian in the Cook County Department of Corrections, he has also had many political involvements. In 2008, he was inducted into the Wendell Phillips High School Hall of Fame, and in 2009 he was awarded the Walter Dyett Lifetime Achievement Award by the Jazz Institute of Chicago. He is the executive director of the Hyde Park Jazz Society. He was interviewed by Rebecca Zorach in August 2011.

RZ: You came to Chicago at a young age, is that right?

JW: Yes, I was born John Albert Wright in Louisville, Kentucky, September 7, 1934. My family migrated to Chicago, IL in 1936.

RZ: So you were quite young.

JW: I was quite young, just two years old. Anyway, we moved to Chicago and resided on the West side at 1848 West Roosevelt Road. My mother was an Evangelist at Victory Mission Church, where the Lighthouse for the Blind sits today. We stayed there for approximately six years, and moved to the South Side where I attended Benjamin Wright Raymond Elementary and Wendell Phillips High School.

RZ: And so where did you live on the South Side?

JW: We moved to 3666 South Wabash. I lived directly across from Benjamin Wright Raymond School. I remember our telephone number too. BOulevard 8-3695.

RZ: Wow.

JW: That was many years ago. I was already playing piano. Mother said I was picking out melodies at the age of three. At the age of seven, I was playing for her church. At the age of 13 or 14, I was playing the organ for Christian Hope M.B. Baptist Church under Rev. H.B. Brady, until I enlisted into the military (Army) where I was introduced to jazz.

RZ: So it was actually the military that introduced you to jazz?

JW: Well, after basic training, I was sent overseas, during the Korean War. My unit was shipped to Korea and they sent me the opposite direction, Germany. And when I arrived, they put me into the 7th Army Special Services. I didn’t know they were expecting me. The State Department seemed to think I knew everything about jazz. Little did they know; I knew nothing about jazz! After being there for three years, two and a half years in Special Services with all the great musicians; (Walt Dickerson (vibes), Lou Blackburn (trombone), and many others – that’s where I got my PHD in jazz. After being discharged, I had my mind up as what I wanted to do. I wanted be a jazz musician, chase pretty women, and drink a lot of whiskey. I did exactly that, and it almost killed me. That was a lesson to be learned!

The early years in Chicago, I had the chance to play with a lot of musicians. Back in the late 50’s, the scales of a nightly musician was $7.50 to 10 dollars at the most, and some places we wouldn’t even get 7.50, we’d get 5 to 6 dollars. We had to play music from 8 o’clock pm until 2 a.m., and most of these places had four o’clock licenses, which we had to play till 4 o’clock Sunday thru Friday and 5 o’clock on Saturdays.

RZ: And that was for $7.50?

JW: That’s right, with no air conditioning, and no free food either. You know, those were the things we had to do. I remember my younger days playing piano and bass, I didn’t have a car, a lot of the jobs I had to play was on the North and West Side, and I had to carry my fiddle on the street car—back in those days we had streetcars, a few busses, and El’s — and I had to carry that big bass. I thought about it, and I said to myself, “wait, let me put this bass down, piano players sometimes make more than bass players, and I don’t have to lug all this equipment.” Well, I didn’t carry an amplifier in those days, we didn’t use amplifiers, and we just played with the strength of the bass.

RZ: So you played all different instruments?

JW: Well, I could, but I always preferred piano.

RZ: So, just to back up a little bit in time, when you were growing up in Chicago, was there always music around you, was it something that was a special thing that you did…?

JW: Always.

RZ: And there were always people around who were musicians.

JW: There was always music around me. My mother was a Pentecostal Evangelist missionary, and in our home there was no blues, no jazz, no card playing, no dice, no drinking and no smoking. Back in the day, they called us Holy Rollers Sanctified. So, I didn’t know anything about none of that craft, and I didn’t know anything about the music, other than what I heard on the radio, which was boogie-woogie and some blues. And I loved it! I tried to play it also without my mother knowing it, but it didn’t really rub off on me. There was always music, my mother played piano, my two older sisters played piano and sang, and my younger sister, today plays the piano and direct the choir at her church. My brother wasn’t into music at all. In my mother’s church, in the mornings, Moody Bible Institute would come over and bring a few instruments, and in the evening, Wheaton College would come and bring all the instruments for us to get familiar with all of the sounds of different instruments – that’s when I really got into music, because I learned the different sound of each instrument.

RZ: So that was church music, hymns and gospel—

JW: Which I love today, mm-hm, that was my first introduction to the music world. And as I grew older, in high school, I ran across a lot of musicians in high school who was trying to play jazz, like George Shearing & Erroll Garner, and different artists, but it really didn’t dawn on me that I wanted to be a jazz musician until I went overseas and was put into Special Services. When I really heard jazz, the real meaning of jazz, I really caught on fast. I said, this is what I want to do is be a jazz musician and this is what I did. I was fortunate to meet some of the world’s great musicians then, who later became great musicians after they got out of the service, and some was already great before they went into service, such as Eddie Fisher, Victor Mo, Johnny Fontanet out of Lionel Hampton’s band, Lou Blackburn who played with all the greats, with Duke Ellington and Count Basie, Walt Dickerson, great vibraphonist, and it, it goes on and on. I couldn’t wait to get my first job. When I came home from the military, my first job was on the West Side of Chicago at a place called, Fifth Jack, it was located at Fifth Ave. & Jackson Blvd. and it was operator by two prominent gangsters, they’re deceased now, I guess I can use their names: Butch English and Tony Accardo. I played there for one month. They told me to bring in a couple of horn players on the weekends! Well, I had met a couple of good horn players and I had invited them to play with me one weekend, they were the famous Gene Ammons, and Dexter Gordon, both tenor saxophonists.

Here’s a little story on Dexter Gordon. That Friday or Saturday night, my gig mind you, Dexter Gordon called a ballad I did not know, and I was fumbling over the keys, and he said to me, “John, lay out!” I think every musician in the world must have been there that night because even to this day, I can be out in the jazz world and one of the old musicians will see me and say, “Hey, John Wright, lay out!” [laughter] the title of that song was “Darn that Dream.” I went home and stayed up all day until I had gotten it up under my fingers. I said, no one would ever again in life tell me to lay out, especially on my gig! That was back in the mid ‘50’s.

RZ: So what were some of the other places that you played?

JW: I played all over the South Side, in my early days getting out of the military, just to get my feet wet, and get to know the musicians, I went to many clubs. There were so many clubs in Chicago, a lot of them I didn’t play, but I frequent them, just to meet the musicians, and then I met some of them later on and we played a lot of gigs together. At any point of 63rd and Cottage Grove, east, west, north, and south there was always good music, local and out of town musicians playing. Do you want me to name some of the clubs?

RZ: Sure, yeah.

JW: Oh, there was the Flamingo Club, Basin Street, Blue Heaven, the Cotton Club, The Pit, Pershing Lounge, the C and C Lounge, McKee’s, the Clover Club, Crown Propeller, The Flame. The Sutherland, on 47th Street — there were so many clubs, Kitty Kat Stage/lounge and Club Modern. A lot of them had dances, with the Ballroom Park, Parkway and the South Parkway Ballrooms, and there were plenty of clubs in Old Town, I played a lot of clubs in Old Town, the Midas Touch, The K54, Hungry I, Cracker Barrel, and there were many more places I played in Old Town.

RZ: And in Old Town, that would have been more of a white crowd?

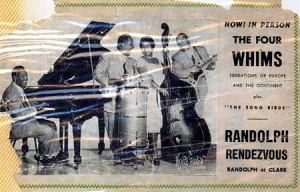

JW: Well, it was more of a white crowd when I first came home from the military, but shortly after, Old Town became a very mixed crowd. My first full-time job (5 nighters) was downtown in the Loop, where the Civic Center sits today, on the corner of Randolph and Clark Streets, there was a club called the Randolph Rendezvous, I played there five nights a week, with Jelly Holt’s crew, and that was mostly whites. But then, it was cattycorner to the old Sherman House Hotel, that’s all torn down now. But even back then, Jelly Holt was with his own group, a group called the Five Blazes, back in the day, they were very prominent well known group doing R&B and standards. When the group broke up, he formed a group called the Four Whims.  I was one of the Four Whims and the youngest of the group, I was about 21. Frankie Rue was the guitarist in the group, he was formerly with a group called The Ravens, from Boston, and Tiny Davis’ daughter, who was the leader of the Rhythm of Sweethearts, that was an all-girls band. Her daughter played bass with us, Dorothy Houston, and Jelly was the drummer and the vocalist. We would play from 9 pm to 4 am with a 30-minute break in between. We had about five, six, maybe seven girl singers; they were very good singers, and also B-drinkers. Well, B-drinkers back in the day; when a man walked in and saw a young lady sitting at the bar, they all would buy the lady a drink, but the ladies didn’t drink the drink, they’d work with the bartender, they would spit the drink back in another glass, and, that’s how things were. See, Chicago in the 40s and 50s was convinced it was the Convention Center of the world, and especially downtown on the strip, on Randolph Street, from the lakefront all the way to LaSalle, was considered the downtown strip, so you had a convention in town every week, and it was money, money, money, and more money. At that time, I was making $125.00 dollars a week, taking home 2 or 3 hundred dollars every night in tips! The conventioneer would just be throwing money around, wow. We had one fellow who came in once a month, Bob King, from the famous King Ranch in Texas, he’d walked in with four bodyguards, and two would be on the Clark Street side and the other two would be on the Randolph Street side, and we let him have the rule of the club. He would walk into the bar, throwing hundred dollar bills up in the place and everything we played was Texas. How High The Moon, Texas; Whatever the Song Was, Texas; Star Spangled Banner, Texas. That’s the kind of town Chicago was: wide-open. There was a lot of money being made in those days. We played jazz and then on Sundays we had a jam session, from 3pm to 9pm, and all the musicians would come for the jam sessions.

I was one of the Four Whims and the youngest of the group, I was about 21. Frankie Rue was the guitarist in the group, he was formerly with a group called The Ravens, from Boston, and Tiny Davis’ daughter, who was the leader of the Rhythm of Sweethearts, that was an all-girls band. Her daughter played bass with us, Dorothy Houston, and Jelly was the drummer and the vocalist. We would play from 9 pm to 4 am with a 30-minute break in between. We had about five, six, maybe seven girl singers; they were very good singers, and also B-drinkers. Well, B-drinkers back in the day; when a man walked in and saw a young lady sitting at the bar, they all would buy the lady a drink, but the ladies didn’t drink the drink, they’d work with the bartender, they would spit the drink back in another glass, and, that’s how things were. See, Chicago in the 40s and 50s was convinced it was the Convention Center of the world, and especially downtown on the strip, on Randolph Street, from the lakefront all the way to LaSalle, was considered the downtown strip, so you had a convention in town every week, and it was money, money, money, and more money. At that time, I was making $125.00 dollars a week, taking home 2 or 3 hundred dollars every night in tips! The conventioneer would just be throwing money around, wow. We had one fellow who came in once a month, Bob King, from the famous King Ranch in Texas, he’d walked in with four bodyguards, and two would be on the Clark Street side and the other two would be on the Randolph Street side, and we let him have the rule of the club. He would walk into the bar, throwing hundred dollar bills up in the place and everything we played was Texas. How High The Moon, Texas; Whatever the Song Was, Texas; Star Spangled Banner, Texas. That’s the kind of town Chicago was: wide-open. There was a lot of money being made in those days. We played jazz and then on Sundays we had a jam session, from 3pm to 9pm, and all the musicians would come for the jam sessions.

RZ: And where was that?

JW: Clark and Randolph, place called the Randolph Rendezvous. And all the big bands would stay in the Sherman House Hotel; Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, all the big bands that came to Chicago, and the musicians would come over and play with us, at the jam session. That’s how I got to know a lot of musicians, at such a young age. That was a nice experience; I stayed there for five years. Then, one day, a fellow walked in and said, “I’m from New York, I’m a hiring man for one of the companies in New York, and I’ve got a spot for you. Would you like to come to New York and record?” Well, I’ve heard of Prestige Records and Riverside, Coral, and Blue Note, those were the most prestigious jazz records back in the day. Quite naturally, I said yes. So, he gave me a plane ticket and $500. In August 1960, I went to New York City and that’s where I got to record five albums on Prestige Records.

RZ: And that was with your trio?

JW: Yes, my trio, and I called it South Side Soul. That was my first album and it was talking about the streets of Chicago; South Side Soul; Sin Corner (Sin Corner was about every corner); Amen Corner (Amen Corner was the churches); 63th and Cottage Grove; 35th Street Blues, 47th Street (47th street was a red-light district) and LaSalle Street was the financial district. The blocks on State Street, Wentworth, and Cottage Grove, were always storefront churches. It was about two or three storefront churches in every block.

RZ: There still are a lot of storefront churches.

JW: Yes, plus taverns, and barbeque houses. I called them the red-light district. Chicago was wide open.

RZ: How did you decide to do a kind of portrait of the South Side?

JW: Well, by seeing the South Side. As I mentioned, I grew up on the South Side and knew what was going on as a young man. On 35th Street, Smitty’s Corner was where I first started hearing blues and jazz, and there was another place on 38th and State Street, the Tick-Tock Club. I used to go in there and try to play as a youngster, but I had to put my age up. I’d always act like I was older and I never had a problem. You see these things going on, but I wasn’t really into jazz because I didn’t ever think that I could play it. I knew how to play church songs and all the gospel tunes, because I always played at the church. I played behind some of the great gospel singers. A lot of them have passed on; a few just passed this year: Albertina Walker and Delois Barrett Campbell. I remember them from Reverend Paxton True Light Baptist Church where The Caravans came out under the Reverend James Cleveland, he became a great singer, and later he had his church in California. I was raised with the Reverend Brunson as a child, who started the Thompson Community Singers; we grew up together at my mother’s church on the West Side. I knew all these singers because we had to visit different churches to make the broadcast. Reverend Thurston’s Church, the great, late, Willie Webb, was the organist.

The Gay Singers, and Marvin Yancy’s father, was assistant pastor of Greater Harvest Baptist Church, under Reverend Bobby, which Reverend Robert Anderson came out of that church as well as the vocalist, along with Mahalia Jackson. I played behind her a couple of times as a kid. I got to know Sam Cooke with the Highway QC singers before he went with the Soul Stirrers gospel group and before he became an R&B singer. Lou Rawls & I knew these people from the church. It’s amazing how later on in life I ran across them again.

RZ: But just to go back to South Side Soul for a minute, the, it’s just really striking to me that all of the songs are about places, and that you went to New York to record that album—going to New York to express something about Chicago, about the South Side.

JW: Well, I didn’t know how strong that recording was until later. I was just thinking about the places in Chicago, especially about Sin Corner, as I mentioned I grew up with a very religious family, and they talk against those things. The Amen Corner, the churches, there were all kinds in the blocks, there were Baptist churches, Spiritual churches and you had a church of reform or whatever. All the pastors would be bishops! [laughs] How they elevated themselves to bishops, I’ll never know.

RZ: Which church did your mother belong to?

JW: Beulah Temple Pentecostal Church. It started with five families. Elder Elijah Jones was the Pastor; it was located at 3740 S. State Street. They were affiliated with Elder Flemons and others back in the ‘30’s & 40’s. Rev. Flemons’s church was located on 39th and Cottage Grove. Out of Rev. Flemons’s church, many years later, came the Dr. Rev. Arthur Brazier which he became the Pastor of the mega church today. It’s the Apostolic House of God…

RZ: Bishop Brazier.

JW: Yes, later he became the Pastor. Now his son, Byron Brazier is the Pastor today. That was how my mother’s church started. I remembered back in the early 50s, when the church split, and they weren’t Church of God in Christ, because Bishop Ford, at that time was the pastor of St. Paul’s Church of God in Christ. There was a separate identity from the Pentecostal, well, they all were Assembly, Pentecostal Assembly, but there was a division, and my mother’s church, they broke away from the council because of the baptism. My mother’s church believed in being baptized in the Father, Son and the Holy Ghost, and the other Pentecostal people believed Acts 2:38, being baptized in Jesus’ name. So, that’s why the church split. Same faith! But different baptism. And it didn’t really make sense to me then, it don’t make sense to me now!

RZ: Right! So, I’m wondering when you were playing in Chicago and part of this, seeing all these different jazz musicians, and it was really a sense of community there among the musicians?

JW: Sure, it was and it is today. I met a lot of the greats, not only in Chicago, but from different parts of the world. I met Louis Jordan, T-Bone Walker, Ben Webster, Yusef Lateef, Roland Kirk, and there was so many more, all at a young age. I met so many great musicians. I also had the chance to play with them such as; Jack McDuff, Groove Holmes, the organist Jimmy Smith, the Jones Brothers (Alvin Jones & Thad Jones), who took over Count Basie’s band after he passed, in 1986. I was in Asia (Singapore) when the Count died.

RZ: Touring?

JW: I was touring, yes. We toured the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, Japan, Thailand, you name it. As I mentioned, being in the military, I traveled many countries in Europe, including France and England.

RZ: When did you first go to Europe? You were there in the Army?

JW: Yes, that was the first time. I went over there in July 1952.

RZ: And then did you go back again as a musician?

JW: Yes, we went back as civilians. We went for some gigs there in Heidelberg, K-54, and Jazzkeller in Frankfurt, we played a couple of clubs in Berlin, all over Bern and Switzerland, Zurich and. You just name it; we just traveled and did a lot of playing.

RZ: Back when you were in Chicago, was there much discussion of politics? It’s the same period as the Civil Rights Movement…

JW: Well, I was part of the Civil Rights Movement. The first time I marched was in Gage Park. Ben Branch was part of the movement and affiliated with Jesse Jackson. They thought that I and a few other fellows should never march, because we didn’t have much tolerance, and what they wanted was people to march who could withstand the dogs and the throwing the bricks and rocks and the name calling, I wasn’t ready for that, just coming out of the military, seeing in the South how we were treated, in the early 50s, black and white toilets and white water fountains, we had to go to the back of a restaurant to eat, and I never would even eat, cause I knew what they’d put in the food. See, I saw that for the first time, walking the streets of Arkansas, Fort Smith and they telling me I couldn’t walk on that street, I had to go where the blacks are supposed to be, and I’m in uniform. So, when I came back and I was discharged and they were in the city of Chicago when the great Martin Luther King, came to Chicago, quite naturally I was ready for that movement. The Black Panther Movement, too, I was a friend of Fred Hampton. But I never got really involved, because the music kept me occupied. They were a nonviolent group!

RZ: The Black Panthers?

JW: They were all college kids! They weren’t thugs like the Blackstone Rangers and other gang members. Black Panthers came later. They were college students that were fighting for equality. They wanted Black Power. The whites even took the black Olympic athletes metals from them because they clenched their fist stating they want equality.

RZ: Did you ever go to the South Side Community Art Center?

JW: Yes I did. That’s where I first met Ms. Margaret Burroughs. She was a Grammar school teacher which one of my closest friends was her student, he’s deceased now. Then she moved to Burke Elementary School, DuSable High School, and Malcolm X College. She became a Cook County Commissioner. Margaret Burroughs did a lot of things. While she was at Burke, she wrote a paperback magazine called Jasper and the Little Drummer Boy. Walter Perkins later recorded Little Drummer Boy. He also played with me on one of my Prestige albums (Mr. Soul). Perkins and I was in the army together, I was in Special Services and he was in Frankfurt in an infantry outfit. He was the little drummer boy that she wrote about. Throughout Margaret Burroughs’ life, we kept up with each other and all our little jazz events we had — she was always there. She was just a beautiful woman. I had to go over to her Art Center which was located at 38th and Michigan. I lived at 37th and Wabash, so by us living so close to her studio, we were always there. Anyway, I met a couple of great artists there; they always had something going on with Ms. Burroughs.

RZ: And music sometimes too?

JW: Oh yeah! They had music; music always went along with art. Even today in Old Town, I was working with this fellow that had his own gallery, his name was Fox, and he had a lot of buyers back in the 60s. A couple of fellows I know had their own gallery, I can’t recall their names now, but one of them still have a gallery on 35th & King Drive, the street name was called South Park and before South Park, it was the Grand Boulevard. I played a couple of times in his gallery.

Evening in honor of John Wright organized by the Hyde Park Jazz Society at the Checkerboard Lounge in 2008

RZ: I’m wondering about jazz in Hyde Park, and how it changed with urban renewal?

JW: Well, I belong to the James Wagner Hyde Park Jazz Society. Dr. James Wagner founded the society seven years ago. He was the one that influenced everyone to keep jazz alive in Hyde Park. When he was going to the University of Chicago, before he became the director of the School of Medicine, he would do his homework sitting in the Beehive listening to jazz! That’s how he got introduced to jazz. All the clubs in Hyde Park stayed in Hyde Park. He had a hand in keeping the clubs open. He devoted his life to jazz. There were a lot of nice clubs; Chances, Mellow Yellow, and the Beehive, which the late great Charlie Parker and Miles Davis played.

RZ: Where was the Beehive?

JW: It was on 55th and Harper. I had a chance to see Charlie Parker just before he died. When I came home from the military in February ’55, I think he died in March, and he happened to be playing over there. He was so sick he could hardly play. He would drink a glass of milk to keep himself alert to play.

Jean Wright: Did he mention playing at Philanders? There is a hotel in Oak Park called the Carleton Hotel and the name of the restaurant in the hotel was Philanders. He played there over twenty years, once a week. Everybody that was somebody patronized that restaurant including all the great musicians in the Chicagoland area.

RZ: So maybe I’ll just ask you one more sort of general question about the relationship of art and politics. Some people I’ve talked to say they have their politics and they have their art form and those two things are separate, and others think of them as very closely linked. So when I ask this question I’m not necessarily expecting any particular answer. Do you think that music can be transformative of society, or even transformative of people on an individual level?

JW: I think so. Especially jazz, and, sorry to say this, I don’t want to be a lost art. But the generation coming up now, who has control of finances and different organizations are younger. They seem to think smooth jazz, hip-hop and rap is jazz. That’s not jazz. To keep the real art form along, we have to have societies like the Chicago Jazz Institute, the Little Links. These are High School children who are really studying the art form, and they’re studying from the masters, from all the way back from Art Tatum to Dizzy Gillespie, and Charlie Parker even up to John Coltrane today. They’re learning the real art, and I think if we had more people who knew more about jazz, or would let someone that knows about jazz, open these institutions up to our youth—I’m from the old school and I like to see jazz stay as jazz straight ahead.

RZ: So what’s important about jazz straight ahead?

JW: Because you have to see that, jazz comes from the soul, it comes from Africa, from slavery, and on up to now, through the blues era and all. These kids now get one song and they get a rhyme and get four changes and they think its music. Jazz has progressed to where it’s so sophisticated it’s in the schools, and we have different schools that teach jazz now; Hartford School of Music, Berkley, Duke Ellington School, Julliard, and downtown, Columbia, where they learn the technique, and the technical part of it. Jazz comes from improvisation, taking a piece of music and playing the way you like it, the way you feel it. Usually when you do that, it touches your audience, someone out there will feel it as well. They got away from the swing & the mood, they got so technical. They are just playing lots of notes that have no meaning. As Duke Ellington would say, “it don’t mean a thing if you ain’t got that swing.” So, we’re trying to get back to the way we did it years ago. Before you walk in the club, you heard the beat outside and we would walk in snapping our fingers. You just start swinging and dancing, and it just touch you, it was the same way at the old Sanctified Church, with the hand clap – I remember that from a kid, we’d be playing and praising the lord and a group of white young kids would come in on a Saturday night with pencil and paper and sit in the back. Little did I know what they was doing, they was trying to copy the rhythms of what we were doing. But you can’t put that on paper! That comes from within. It was a time; they said, “white folks can’t jump,” you know, that ain’t true, because I’ve met a lot of white players, even in Europe and Asia, that can play and swing—Sadao Watanabe (alto sax – the Charlie Parker of Japan), that boy, ooh wow! Eddie Keating (piano) from the Philippines, Bobby Chin from Indonesia (piano) and Lewis Tan (drums) from Singapore, I can go on and on! There are a lot of musicians that have never been recognized who are genius, but they never made the big time. So that thing about white men can’t jump, that’s not true. Stan Getz, Zoot Sims and Carl Fontana, these fellows I know could play! And it goes on and on, Art Pepper, a lot of white friends of mine, Wolfgang Knittel, who lives next door to Phil Woods in New Jersey. Some white boys can play, right now, Ira Sullivan, I’ve known him for years! He lives in Florida now and comes back to Chicago at least twice a year to play. What’s in you will come out, regardless of your gender, nationality or age.

RZ: Just to go back to improvisation for a moment, that still requires a certain kind of skill. Would you say you can improvise if you haven’t had training? Or once you have some knowledge and some skill, then can you improvise in a more sophisticated way?

JW: You can improvise if you’ve got the spirit, and the spirit is within. The reason why I’m saying this, I never had a formal lesson in my life, never, and I’m always improving. When playing a piece, you always keep the melody in your head.

RZ: But you have skill.

JW: That comes from the anointing of the gift that comes from the Creator. See what I mean? Every one of us is born with a gift. You just have to find out what your gift is.

RZ: But you can develop a gift, right?

JW: If you live long enough, you will. I’m joking. To be sincere, you have to put the time in, and that takes log of time. It’s like everything else you set your mind to succeed in doing; playing sports: put the time in, and workout; the work ethic: get up early (not being late), eat the right foods, get enough sleep. In all of the above, always be at practice or work on time and stay later if needed, because there’s other kids out there doing the same thing to take you place. That’s why you should put in a 110%. Same thing with you, what you’re doing, you’re putting in another 10% of what you’re doing. You’re not just getting an article for the newspaper or going to the library or looking at the internet, you’re doing what the kids do now, Google, and you go right to the source and get it! And that’s where you really get the meat from.

RZ: That’s sort of what I was asking about, because you said something about kids doing music, that they’ll just put 4 notes together and they’ll get a hit, and it’s sort of like, easy come easy go. And that when you’re talking about real, straight-ahead jazz — I mean, it’s people who have talent, but it’s also people who worked with their talent to develop it.

JW: Yes, I’m looking at a piano player right now who played with Miles Davis his last days before he switched from straight-ahead jazz to playing fusion. Little Bobby Irving, I have listened to him. He has really developed into a great pianist. I’m listening to him and I’m watching him grow. And that’s what I’m talking about, little Irving Pierce is 19. He sounds as if he’s been around here for 40 years. That’s what I’m talking about, putting the time in. When the piano player, what’s his name, had the big band down at 77th not too long ago, used to be with Coltrane? Anyway, he was 21 years old when he joined Art Farmer’s group, the Jazztet in New York, Bobby Timmons was leaving and Bobby turned to Art and said, “I’m bringing in this little piano player.” He said, “well, who is he?” McCoy Tyner, he a 24 year old kid from Philadelphia, and can play very well?” “He’s taking my place!” So, that was the end of that. When McCoy Tyner was there, little Irving Pierce went up to talk to him and he gave him a score, so he wrote a score for him, that’s what I’m talking about. Getting involved, getting our youth involved, really into jazz. Letting them hear, but most of our young musicians really don’t know whose shoulders they’re standing on, because it was a young saxophonist out of Rich South High School in Matteson where we live, and the band was playing, he was sounding great. So I ask one of the fellows to take me up to him, I went to speak to him, and I asked, “young man, who’s your idol, John Coltrane? Have you ever heard of Coleman Hawkins? Lester Young? Johnny Parker, Gene Ammons, Sonny Stitt?” He replied “No, sir!” I said do some research. If you don’t know where you came from, how do you know where you going!

RZ: Why don’t they know where they’re coming from?

JW: Because the teachers don’t know themselves. The teachers who’re teaching today, doesn’t know the fundamentals. They don’t know the struggles. They don’t know what happened in 1886, after the Civil War. They don’t know who stole the ship from Louisiana, and then taking that ship to Mobile, picked their families up. They went to the Carolina’s and took down a Confederate flag, and drove it all the way north. Abraham Lincoln congratulated them and he later became one of the first black congressmen, Robert Smalls. They don’t know history! They don’t know when the old mothers of slavery were making quilts, the masters thought they were making something to keep warm, they were maps! The double rings you saw in that, that didn’t mean a double wedding that meant when you get to a safe house, you heard the bell in the belfry ring twice which meant move on to the next safe house. When they thought you were bedding down for the night, wade in the water, thought they were relaxing, they was getting to the Underground Railroad which was lead by Harriet Tubman. So, they don’t even know how the drums became the first instrument and to jazz, they all came from Africa. It’s a lost cause, because the ones who know the history are dying off, and if they don’t know the oral history, they are lost. But then, when you study history, you weren’t by yourself! There were a lot of folks, John Ross, first Cherokee Indian who really educated in the white man’s missionary schools, it goes on and on. I’m so fortunate to have a grandfather who was educated in Will Roger’s Seminary [the Cherokee Male Seminary] who became the founder of the Metropolitan Baptist Church on the West Side, also who graduated from John Marshall Law School, who taught us Black, White and Indian history because my grandmother was Irish therefore, my mother was half Irish: we were all mixed up together.

RZ: So he taught you at home?

JW: He taught all of us at home.

RZ: So, just one more question about history, and how it’s being taught, or not, whether it’s in schools or in families. Going back to Margaret Burroughs for a moment, she really championed the teaching of black history…

JW: Ms. McCloud, my sixth grade teacher in Raymond School, she taught black history, she had plates and knives and forks, books, young girls had to learn posture, how to hold themselves up.

A young lady couldn’t walk into her classroom unless she had a ribbon in her hair nor could a young man walk in with his shirt collar open, it had to be closed if it had a collar. Ms. McCloud had a closet full of ties! If you didn’t have on a tie, she would get one of her ties and put it on you. If your hygiene was bad, she would excuse you and take you down and wash you up. If you didn’t have the right clothing, she would you to her house on the weekends, have you to do some chores, then go buy you some shoes and pants or dress. Not only did she educate the mind, but the body, and soul too. By teaching them art, that gave them another form of getting outside of yourself. Not hanging on the street, something else to do! That’s why a lot of kids learn how to do murals and different things, because of the art center.

Getting back to Margaret Burroughs, not only she had a lot of books, she had a lot of writings and poetry to teach. I had the pleasure of meeting Gwendolyn Brooks. When I was the librarian at Cook County jail, she donated two thousand of the book [Blacks], I have a copy of one books. These are not only the people that taught their craft, but they taught you stability, how to be a young woman, be a man, even. And music, music was part of it! I was boxing as a kid, and I boxed with the CYO, the Catholic Youth Organization, and whether I was Catholic or not, I had to go to mass, and go through the rituals, you know, before I could get in that arena to box. And I was baptized as a Pentecostal, and none of us could go to the shore and do anything unless we went to Sunday school and church! See, that’s another thing we’ve gotten away from, principles! You know, whether you believed in something, you had to believe in something. And your parents was always there to help you with your homework, but nowadays the kids have drop out, they gang up, these youngsters, but they don’t even know third grade math!

RZ: So what happened?

JW: It was a breakdown with the economy. These young mothers found out by having a baby, they didn’t have to work. They didn’t have to go to school and that for one, two, three, four, generations. My grandfather always said, “education is the only way to freedom”. If you go through my front room, hallway, family room and my garage, you see artwork all over; Jean can tell you everything about that. I was a precinct captain for twenty-some years…

RZ: Where was that?

JW: The 7th ward, 14th precinct, I was with John Stroger; he was my committeeman, long before he even became alderman. And from there, I went to the Cook County Sheriff’s Department, and I retired from the sheriff’s department. But I was still playing music. So I had an interesting life. I am on my fourth marriage. I buried three wives. Between my four wives, I am the father of 11 children, grandfather of 33, great-grandfather of 19, and great-great grandfather of 6. But anyway, it’s been a great experience; music has always been my life. I do enjoy politics; I was in politics long before Harold Washington. We were great politicians, because people in our precinct knew who we were. We got things done. Every home had two, 50 barrel garbage cans, every commercial had mesh cans, and we started the block corps, the whistle-stop program for the women who were late coming home, medical alert bracelets, and anybody that had a birthday would call over to the ward office, brought the horses out, block the streets off, brought out water platoon, supplied ice cream and hot dogs with the children. Everybody turned out; I even had a couple of cases of whiskey. If it was a major election, all the liquor stores were close until 6:00pm, and I would supply coffee and donuts for that came to work with us. I also had money to pay my people and a couple of cars to pick up the elderly and the sick. So we had 100% turnout, sand that’s why when we had the meetings, Walter Jacobsen pulled the covers on us and said we have to get jobs, but that’s another story. That’s how it was done! It was close knit with the police and the fire department. We also had a community center for the children. The YMCA, you had the music department, and we built a new recreation system out there for the kids, art department for them, swimming and baskets. They read poetry, that’s the first line of rapping. So I’m not against a lot of that stuff but when you say jazz, then I’m from the old school, I just love it, and it is part of my life. A lot of the youngsters would love it too if they’d hear it! It’s got to be taught, but you see the way the economy is now, they’re taking the arts out of the schools. But I always said, “if I had my eyes I would have done more with the youth.” I love working with the youth, they’re the future of our country! And they have to be taught, and be taught right. There’s something more than just 37th Street, 47th Street, 83rd Street or whatever street there is, some of those kids live and die right here in the city, never been far as Gary, IN, Chicago, IL, Racine, WI, or Waterloo, IO, they don’t even know where St. Louis is, they don’t even know where Route 66 is! It’s the same here with the suburbs, a lot of kids have never been any farther than Harvey, or Country Club Hills.

Lavon Pettis: Did you tell her about your work with the Black Panther Party?

JW: I told her I did, we did some things together, but I was outlawed from the march at Gage Park, and a lot of the fellows from the Jesse Jackson days thought I was too militant. I couldn’t stand a brick being thrown.

RZ: You would throw it back?

JW: I probably did more than that. You couldn’t even carry a pocket knife with you. You had to be screened for that. Back then, I didn’t have enough Christianity in me to turn the other cheek. Three years while I was in the military, I never heard that word “nigger”. Soon as I got back to Chicago, hit the South Side, that’s what we all called each other. [chuckles] I had to get used to that word again! One time in school, we were singing that Steven Foster song, “and I heard the gentle voices calling old black Joe,” and this white boy was sitting in front of me, he kept turning around looking at me saying “old black John!” Then the fight began [chuckle]. The song was Joe, not John. My first wife was African-American, my second wife was Creole, my third was Polish, and my wife today is Black American. So, we’re right down the line, huh? I’m an alumnus of Wendell Phillips High School. Hewitt Jackson and Ernest Millhouse are Wendell Phillips alumni as well, and one of our first black naval commanders. They are a part of the alumni committee and what they do in school when they have an induction into the hall of fame, they all go around to different classrooms and let them know what’s going on, what happened in their particular generation. You’re not going to get this information from the history books, because it’s not in the history books, just a certain amount, and if they don’t go around letting these children know this—like I said, if you don’t know where you came from, we wouldn’t have all the trouble we be having now, with all these drive-by shootings and everything else. But we have to go into these parents’ homes and educate them first! Got to hold these parents accountable for these children. And then we can start working, education, got to educate the mind as well. But it’s hard to try to teach when the kids come to school hungry and their parents been out drugging and fighting all night, you know.

And all musicians were not dope addicts! Fanatics! They were decent human beings with a message. And it’s just like me, I could never really stand up in front of a room and give a lecture, but if you sit me down in front of a piano, you can hear my soul, you can hear where I’m coming from through music. And while someone else is reciting a poem, maybe by Paul Laurence Dunbar. That works together—I’ve seen it work! The workshops have music entwined with the arts. Now they have expanded on to film, the visual arts and everything else. But it started from the grandmother and the mother teaching, how to take a thimble in one hand and a needle in the other hand, making a fist, darning a sock. Today, the same kids, sitting around a table, “oh Grandma, what a big blunt you can roll!” Marijuana. See where we came from? “What great pies you make, Grandma!” See, there’s a difference. Most communities have gotten away from the family. You know, it’s an old African saying, “it takes a village to raise a child.” We’ve gotten away from that. Migration was one of the big reasons, the separation. What I was doing with the inmates, with the Cook County Department of Corrections, in the library I was doing the same thing. I changed the whole format, I went to Sheriff O’Grady, he said, “No funds,” same thing when I worked with Sheriff Sheehan, no funds, out of my pocket and whoever, I had musicians from Local 10-208 bring me instruments. I took a piano down with my own sound system because lot of the time they couldn’t use their sound system cause something else was going on, and then musicians she gave me a trumpet, trombone, I had a choir, male and female, I had a band, sometimes it looked like I had the whole of 10-208 locked up. The art colony and performance group! And I had some of the lieutenants of the Latin Kings and the Disciples, all of them, with lighting crew and writing scripts, and we would go on the road, too, we had 14 divisions, we used to go to different divisions. I used to have clean clothes, I’d bring cologne from the house, all that stuff, shine shoes, cut hair every week, and we would perform. And faith comes in there, because people say, “I don’t believe in” and I say, “yes, you do. If you didn’t have faith you couldn’t put one foot in front of the other. It takes faith.” So, you know, what I’m trying to say—music, and art and poetry and all other visual arts in the world, will make this world a better place. I’ve seen it.

I used to see john play with the Oscar lindsey trio. You might remember my mom add dad. Sandy and ruth

.they would see you a lot.i loved your playing john. It was great reading about your life story. My name is Wayne and I’m 69 years now retired in vegas.my sister was judy. God bless you I would love to hear from you. You probably saw me 40 years ago. My parents would be 99. Sincerely wayne skurow.